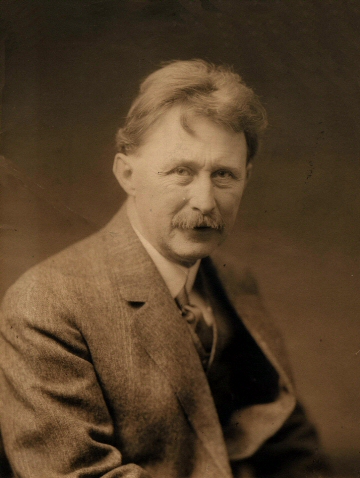

ROBERT STRONG WOODWARD:

"PAINTER OF NEW ENGLAND'S HILLS AND FARMS"BY ERNEST W. WATSON

A photograph by F. Earl Williams of

the north window extension from outside.

"As I write-early in August--- it is still open season for out door painting. Here and there throughout the countryside the glint of canvas or paper, white against summer greens, betrays the presence of artists who worship at nature's shrine. Under a sheltering maple one brushes-in the sweep of rolling meadows; at the edge of a mountain brook a watercolorist dips his pail or washes his palette; among the rocks on a rugged coast, a marine painter matches his colors with the hues of a sunlit harbor.

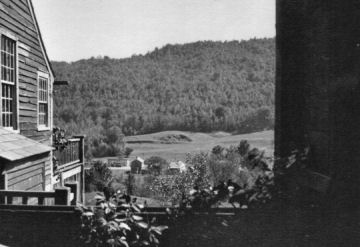

A View of Ashfield Rd. Buckland, MA

A View of Ashfield Rd. Buckland, MA

Yes, far and away from 57th Street's innovations, scarcely aware, even, of their existence, there are many ardent practitioners known as 'Nature painters.' These disciples of the great outdoors paint frankly what they see before them, rearranging and composing, to be sure, and-the best of them-distinguishing their work by poetic insight; but offering us, in the end, quite faithful transcripts of expertly selected subjects. They are concerned with the universal concept of beauty and they are not diverted by the changing idioms of advanced philosophies. Successive waves of 'isms' have swept over them without evoking so much as an upward glance. Their canvases, in consequence, induce quiet contemplation and satisfying enjoyment rather than heated controversy. Not being 'news' they make the headlines far less often than the latest flowerings of modernism. They find their way into countless homes of people who may claim little sophistication in art but who know what they like. And the most creative practitioners enjoy great esteem, at least in conservative quarters of the painter's world. Prominent in this school of realists is Robert Strong Woodward, whose canvases depicting scenes in the beautiful Deerfield Valley of Massachusetts have been familiar to gallery goers for many years.

TO SEE A FULL SCAN OF THIS ARTICLE CLICK HERE ( Page will open in a new tab)

Young Woodward first row second boy

Young Woodward first row second boy

Finding myself recently not many miles from Woodward's home in Shelburne Falls, I motored over the hills and spent a half-day with one of the most remarkable men I have ever known. Woodward's achievement as an artist - he is distinguished among his fellows and has made his living solely with his brush - is impressive enough; but to have accomplished what he has while confined to a wheelchair during his entire professional life is a truly extraordinary performance. As if the man's physical handicap were not a sufficient challenge to his spirit, two studios were burned to the ground at the beginning of his career, and he has been beset by other difficulties such as have disheartened many a robust person. Even his boyhood days seemed shaped to hinder the lad's making something of himself. His father's business kept the family almost continually on the move, and young Robert's education was a matter of 'catch as catch can' -- he recalls attending eighteen different grammar schools! Finally, at twenty-one, after two and one-half years at Bradley Polytechnic Institute in Peoria, came the paralyzing pistol accident and five long years in California hospitals. Released at last from the hospital, Woodward made his way eastward to Boston where he spent a few months in the life class of the Boston Museum School of Art. This was the extent of his formal art training; he has had no instruction whatsoever in painting.

Woodward in front of the Wells home with the shed just

behind him over his right shoulder that would become

his first studio he called Redgate

From Boston he went to the home of his grandfather at Shelburne Falls. Since early youth he had nourished a passionate love for New England's rugged hills and, now, knowing that he must choose a site for a permanent home, he was inevitably drawn to this scenic region. An old maple sugar house on his grandfather's farm was converted into a studio [Redgate] where he succeeded in earning a meager living at lettering, illuminating and designing bookplates and heraldic devices. This he looked upon as a temporary expedient, for, from the first, he was determined to become a painter. One morning while shaving, he noted the appearance of a gray hair or two. He was thirty. He realized that his career could not be delayed any longer. He took up his brushes and began to paint. He painted for more than a year before he showed his work to anyone. Finally he mustered courage enough to take a number of canvases to Gardner Symons who lived in the neighboring town of Colrain.

Young Woodward, while hopeful of a word of encouragement from this one-time prominent artist in the American School of Naturalism, was scarcely prepared to hear Symons urge him to send a picture to the National Academy's Annual. What astonished him more was to have his canvas accepted and actually hung on the same wall as pictures by the day's notables. One year later when he won the Academy's First Hallgarten Prize- the painting was purchased by Mr. Hallgarten-he considered his career to be effectively launched. Although there were to be discouragements aplenty, honors, too, followed. Museums began to acquire his pictures and finally he was invited to the big Carnegie Show in Pittsburgh. He was earning a national reputation. For the first ten years, Woodward painted seated in a buggy; during the past fifteen he has set up his easel in the tonneau of a large touring car. In both situations he has overcome the handicap of working close to his canvas by unfocusing his eyes to approximate the effect of distant inspection.

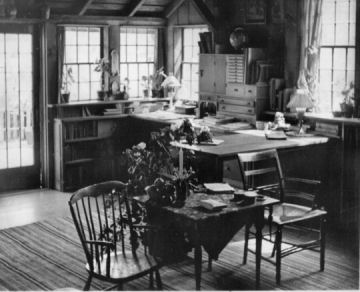

Some of his best-liked pictures are painted in his studio looking out through windows made gay with flowers, pottery, and antique glass, accessories which offer a foil for the distant landscape. How often has he painted his world seen through these panes! Always seeming to discover a fresh approach to give individual distinction to each.

A photograph by F. Earl Williams of

A photograph by F. Earl Williams of

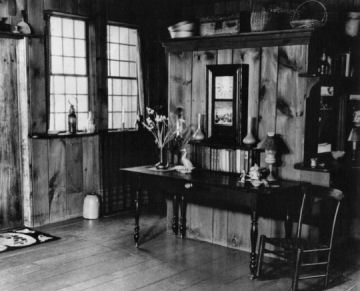

the studio hearth in Woodward's time.

It is well worth a trip to Shelburne Falls just to see Woodward's studio. Once the sturdily timbered structure was a blacksmith shop, of which we are especially reminded by the giant forge bellows that hangs in the fireplace corner. Every studio has its individuality that mirrors the character of its owner. Here, one is immediately impressed by a meticulous orderliness which bespeaks the artist's genius for organization. All is thoughtfully designed for maximum efficiency-cabinets, shelves, tables, desk and all needful appurtenances. It is not a cold efficiency; everything is arranged with what I was going to call good taste. But the word has not enough warmth. It excludes those subtle touches that spell the difference between an "interior decorated" room and one made gracious by the daily ministrations of an artistic conscience. The environment is unusually important to this man to whom home is a bigger chunk of the world than to most of us. His entire establishment-home, grounds, and barns-- is groomed with the same loving care as the studio itself.

A photograph by F. Earl Williams of the North

A photograph by F. Earl Williams of the North

Window with the painting

Frost on the Window

on display for visitors to the studio.

How he manages it I cannot say. A huge brick and stone fireplace occupies one corner of the studio. Woodward told me that from the time a fire is laid during the first chill autumn day until late in the spring the blaze is never allowed to die. It is a matter of companionship rather than physical comfort- the room is well heated by steam. The opposite corner, by a north window, is where the artist brings most of his pictures to completion. He paints his landscapes directly from nature, out of doors, but usually, they are brought into the studio for those final adjustments which can better be made under more favorable conditions of light and after a period of study. Through that window may be seen the subject which, with variations, has been the theme for many canvases. Beginning To Snow, reproduced here in color, was painted from that window and I have seen several other versions of the same theme, all winter pictures.

Unlike Beginning To Snow, most of the others exploit the window itself, its mullions intersecting the distant view. It is in this corner that Woodward exhibits his pictures to visitors-many buyers making a pilgrimage to Shelburne Falls in the summer months. The canvases are stacked in a curtained alcove hard by, and are brought out by an attendant, one at a time, and set in a frame. The usual stack of canvases and papers seen in artists' studios is conspicuously absent from this workroom. Across the room are other windows that have figured in many Woodward canvases. They look out upon majestic hills patterned with meadows and forests.

All of the small panes in these windows are old glass. Toward the completion of the building's restoration as a studio, Woodward was urged to supply the deficiencies with new glass. "No," he replied, "We must be patient and we shall eventually find old glass." This detail is worth mentioning only because it represents a philosophy of perfectionism that evidently controls every action of the man's life. I cannot refrain from telling here of an experience which goes far to epitomize that aspect of Woodward's character which in part must account for his success. When, after the burning of his second studio, he acquired his present property, the problem of restoring an old building and adapting it to his needs loomed large, especially as he did not have the means for it. Should he accomplish the transformation little by little, making the best of inadequate working conditions over a period of years? His answer, "No," was an affirmation of

his faith and an exhibition of the courage that has carried him, victorious, throughout

the years. He borrowed the needed funds and laid aside his income-producing brush for a whole year, devoting himself entirely to the designing, constructing and furnishing of his studio and home. He had to create the right environment

before he could do his best work. There is not much to be said of Woodward's technical methods. They are simple and traditional. He first makes a charcoal layout on his stretched canvas, working directly from the subject. This is kept

around the studio a while for constant study and development. When he is satisfied, he removes all the charcoal that can be rubbed off with a cloth. A faint line pattern remains as a guide for the brush when painting begins. He paints

with a turpentine and oil medium. Often he renders the subject first in pastel. Most of what I have written is the story of the man. You cannot separate a man from his work, especially when a triumphant life vies in interest with his work

itself and when it becomes a symbol of magnificent courage and greatness of spirit. As to Woodward's art, the pictures speak for themselves. They alone are the testimony of his achievement as a painter."

=========================================================

This article was reprinted with permission from American Artist magazine. © 1946 VNU Inc. 770 Broadway, New York, NY 1003. All rights reserved.

NOTE: All the images used were the editorial selection of and exclusive to the website and not that of the magazine. All rights reserved.© 2017

This article is not only an excellent source of information. It contains images of 5 paintings that

we (1) have NO other pictures of nor (2) do we know their current location to this day.

TO SEE A FULL SCAN OF THIS ARTICLE CLICK HERE ( Page will open in a new tab)

BELOW IS A COLLECTION OF SOUTHWICK: THEN & NOW IMAGES FOR YOUR ENJOYMENT

The table by the entry as it appears today.

The table by the entry as it appears today.

The North (Artist) Window as it appears today.

The North (Artist) Window as it appears today.

The North (Artist) Window as it appears today.

The North (Artist) Window as it appears today.

From the porch between studio and house.

From the porch between studio and house.

You can see the balcony off the studio on the left

and the windows which light his desk corner.

photograph by F. Earl Williams

The 'Cobbler's Bench' RSW converted

The 'Cobbler's Bench' RSW converted

to use as a workbench

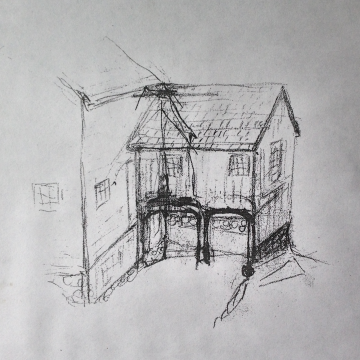

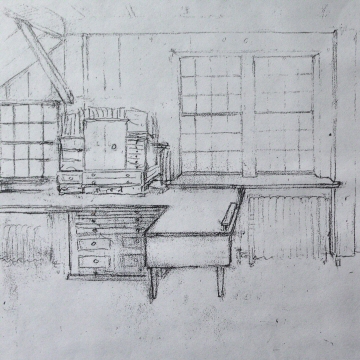

Drawing of RSW's vision

Drawing of RSW's vision

for the barn extension

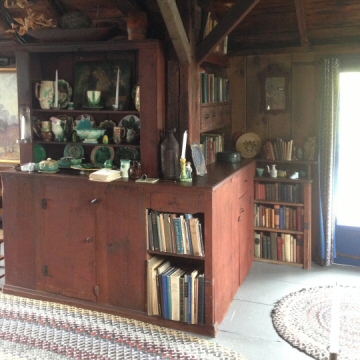

The Bookshelves as it appears today.

The Bookshelves as it appears today.

A near match of the sketch to the left.

Drawing of RSW's vision

Drawing of RSW's vision

for the barn extension

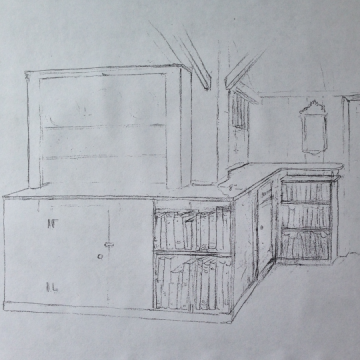

Drawing of RSW's design for

Drawing of RSW's design for

shelves and storage

The Bookshelves as it appears today.

The Bookshelves as it appears today.

A near match of the sketch to the left.

Drawing of RSW's design

Drawing of RSW's design

for his desk area

Outside the balcony door in winter

Outside the balcony door in winter

photograph by F. Earl Williams

The balcony outside the studio

The balcony outside the studio

photograph by F. Earl Williams