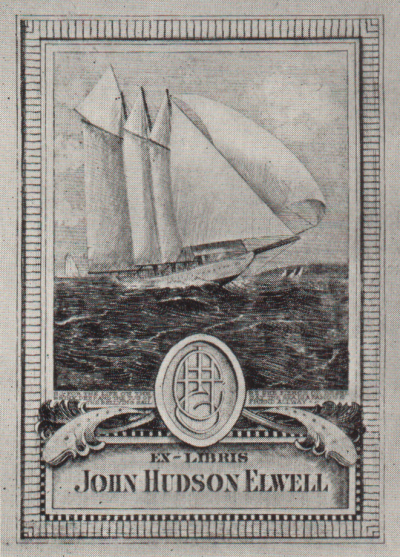

John Hudson Elwell

John Hudson Elwell (1878 -- 1955)

Bookplate Engraver, Designer and Craftsman

John Hudson Elwell

Bookplate engraver, designerand craftsman by Harry Elmore Hurd

When I entered Number thirty Bromfield Street and climbed two flights of stairs to the establishment of the W. H. Brett Company, I tingled with excitement, for I knew that I was about to step backward from the era of mass production and mechanical output to the primitive days of hand-craftsmanship. I was in search of John Hudson Elwell, one of America's foremost designers and engravers of bookplates. The Boston craftsman is also an etcher and painter, but my visit was motivated by the knowledge that the art of creating copper-engraved bookplates is almost a lost art: indeed, Mr. Elwell is one of the five craftsmen in the United States engraving bookplates on copper.

Knowing that John Hudson Elwell had been apprenticed to Reuben Carpenter, the outstanding banknote engraver of the late nineteenth century, I expected to meet a gentleman acquainted with Time and bowed with years of bending over a drawing board. I was not prepared for the athletic man, standing nearly six feet tall, who advanced to welcome me. The firm grip of his hand and the light in his serious brown eyes assured me that I was in the presence of a friendly man. The birth-records of Old Marblehead reveal the fact that John Hudson Elwell was born in 1878 but, as I studied the Yankee face of the man in the double-breasted blue suit, I doubted the birth-record. Possibly his love of beauty keeps him young: we suspect that his devotion to tennis and yachting has subtracted ten years from his age.

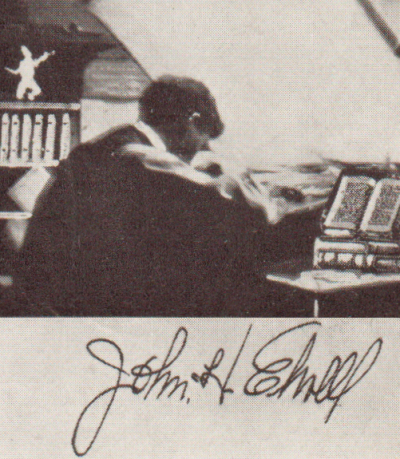

John Elwell at work

One suspects that the craftsman's artistry owes much to his Scottish inheritance, through his mother----a strain dating back to the Stuarts. Other fruits of the family tree include sculptors, architects and painters in oil.

Most fortunate was the fourteen-year old lad to be tutored by Reuben Carpenter, the father of such bookplate engravers as Sidney L Smith and J. Winifred Spenceley. John Hudson Elwell was not content merely to master drawing and the technique of the etching needle and the graver's tools. Entering evening school, he studied six years under Vesper George, Hamilton and Cross, men whose names are famous in the world of art. To beauty the young man added a wide culture showing a special fondness for literature and science. His large library, filed with rare de luxe editions, testifies to his intellectual thirst. There can be no great art without culture. His collection of bookplates, includes the works of E. D. French, Sidney Smith, J. W. Spenceley, George W. Eve, Charles W. Sherburne, A.N. MacDonald, George H. Hopson, Fred Thompson, Reuben Carpenter, Stanly Harrod, Charles Blank, Elisha Bird and Hartley Anderson.

Those persons who worship the cheap, the mechanically made, "the just as good," lack the capacity to appreciate the bookplates of the Boston craftsman. Such persons will turn to "zinc cuts" and photogravure, lovely at their best, but as inferior to copper-engraved plates as the photograph is to a painter's masterpiece. Fully to appreciate the work of any genius, one must acquaint himself with the backgrounds of the creator's art. Aside from connoisseurs, few persons realize the antiquity of the use of bookplates: like the printed book, they trace their origin to Germany, both dating from the middle of the 15th century. Albrecht Durer is known to have engraved six plates between 1503 and 1516, and to have made designs for many others. Theodore Wesly Koch, A. M., Librarian of the University of Michigan, tells us that "the larger and wealthy monasteries used more than one plate. The advent of each new lord abbot was celebrated by the creation of a new plate for the library." Persons of distinction used the armorial bearings of the family as bookplates. Frederich August, duke of Brunswick-ols, in 1786, had sixteen plates.

After the French Revolution, the Jacobean bookplate was developed. This heavy decorative style was in vogue during the Restoration, Queen Anne, and early Georgian days, that is, from 1700 to 1750. Mr. Koch describes the Jacobean plate as "armorial in type: the decoration is limited to a symmetrical grouping of the mantling and an occasional display of palms and wreaths. The mantling surrounds the face of the shield as the periwig of the portraits of the period surrounds the face of the subject. It springs from either side of the helmet into elaborate patterns. Although imported from France, the Jacobean plate assumed English characteristics, developing towards solidity rather than towards gracefulness. These plates have a "carved appearance."

During the middle third of the 18th century, "a flamboyant rococo style of engraving was in vogue," named after Chippendale, the designer of the furniture so highly prized by all lovers of the antique. Chippendale plates are distinguished by "a fanciful arrangement of scroll and shell work, with acanthus-like sprays. The grouping was usually unsymmetrical so as to give a free scope for a great variety of counter-curves. Straight and concentric lines were avoided." The familiar crest of George Washington is in this style.

New styles were developed during the latter third of the 18th century, among which may be found the "ribbon and wreath," pastoral scenes, landscape effects, pictorial compositions and library interiors.

Steel engraving came into use at the beginning of the 19th century, resulting in the continuance of the formality of the previous century. The photo-mechanical process was developed during the latter half of the century. While this process gave greater freedom and ease in the reproduction of the original sketch, it is true that "photo-engraving, or the half-tone process, is hardly a legitimate means of reproducing a bookplate design." In a copperplate engraving, we have, as in a painting, the subject filtered through the personality of the craftsman. This personal equation is the difference between a photographic reproduction and a work of art.

Portrait plates are not common: most of them date from the latter half of the 19th century, although Durer's friend, Bilibald Pirkheimer, pasted a plate of this kind on the back covers of his books.

Mr. Elwell told me the story of the creation of one of his portrait copper engraved plates. Part of the difficulty of portraiture is inherent in the medium, the artist having to copy a photograph which is "grainy" in tone upon a copper plate, which changes the entire complexion of the picture. Mr. Elwell toiled for weeks..months.for fourteen months..upon the portrait in question. A touch would alter the entire complexion of the subjects: a stroke would cast the face in shadow. Sometimes the eyes would jump out of focus and seem to defy correction. The final accomplishment was like a revelation. When the portrait was finished, the plate was entrusted to a messenger with the strict caution to beware of any harm coming to the fruit of fourteen months of creative toil, as "It could not be replaced." Imagine the panic of the craftsman when the messenger telephoned from Cambridge: "I have lost the plate." Mr. Elwell confesses, "I was desperate. I knew that I could never capture the same effect again." The finder of the precious package, upon a subway car floor, carried it to the Lost and Found Department, and thus the masterpiece was saved.

Not always is the artist so fortunate as to be commissioned to engrave the likeness of a woman of lovely character. The average patron is practical first: he desires a thing of utility. Often the craftsman must deal with the idiosyncrasies which so easily beset out human natures; therefore, not all bookplate subjects may be intrinsically beautiful. One always finds, in Mr. Elwell's creations, evidences of the "maker's high seriousness of purpose." His plates possess significance of meaning, dignity, appropriateness and beauty.

I asked Mr. Elwell: "What makes a copper-engraved bookplate so costly?" He replied by telling me a story: "A woman came to me, who just wanted a bookplate. She did not know what she wanted, but, having seen a beautiful bookplate, wanted one similar to it. Then followed a series of conferences. Of course, I had to submit drawings. It is like an architect drawing the plans for a house. The client starts with the idea of an eight-room house: before the sketches are completed he decides to build a twenty-room house. After a long process of elimination, my client decided that she wished to use her ancestral armorial design. I spent twelve hours at the Boston Athenaeum and searching the shelves of the Massachusetts Genealogical Society. Finally the woman took a trip to England to trace her ancestry. A year will be consumed before we are ready to go ahead."

The craftsman then showed me two bookplates, the first designed and engraved by Mr. Elwell for Arthur Chesterton Jameson of 112 Babcock Street, Brookline. This is a memorial bookplate with the portrait of Mr. Jameson's mother, framed in an oval, entwined with a series of connecting links, torch, Adele Chesterton pin, and emblem of Dean 1915, with the words "Carry on," oak leaves and an open book with one leaf taken out.

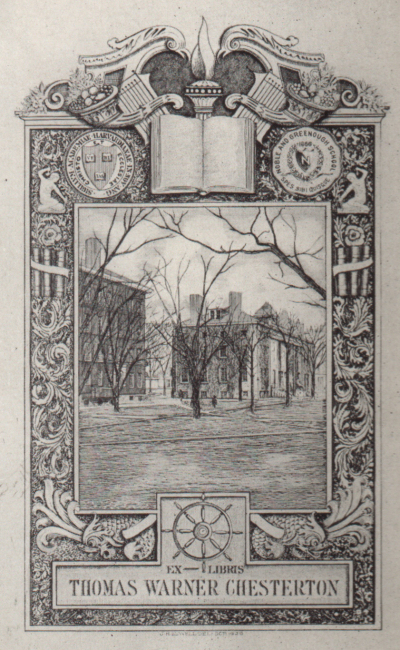

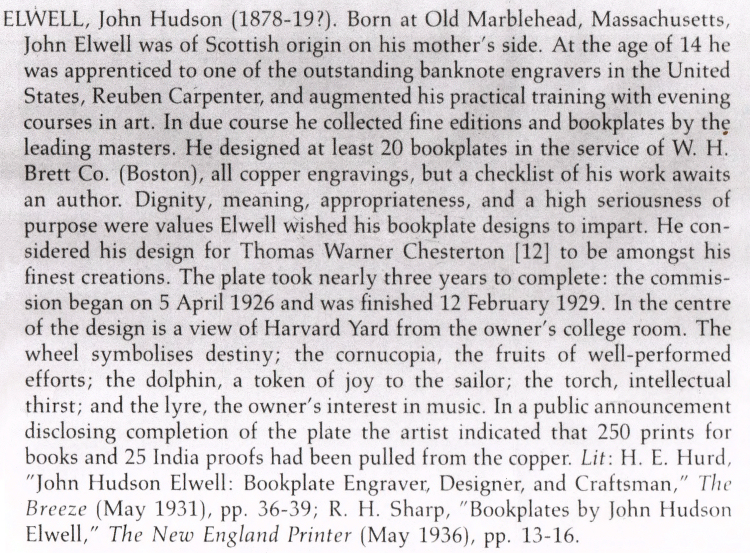

Thomas Chesterton bookplate engraved by John Elwell

The design and engraving of these two bookplates required over two years of creative effort. No shortcuts may be taken by the craftsman who engraves upon copper plates. A master portrait painter may execute several important commissions during the months required by an engraver upon copper plate to create a convincing portrait. Some one has written "Light and shade, warmth, tone, colour, distance, atmosphere are easy words to juggle with, but to have what they stand for always ready on the point of an etching needle is a different matter." In his portraits, Mr. Elwell combines softness with strength, simplicity with seriousness. These vignettes are vital: they are lyrical, complete and beautiful like a Petrarchian sonnet. Each plate is a symbol of a personality, a thumbnail biography.

The Thomas Warner Chesterton plate reveals the craftsman's power to portray the luminosity and silvery quality of the out-of-doors. This plate possesses the dynamic quality which characterized the art of Sidney L. Smith. The architectural quality, the sense of design, the finesse of design in this plate might well be the envy of the world's foremost engravers upon copper plate.

Here we also have illustrated the symbolism of the craft. Look at the wheel: it may be turned to the right or left, thus bringing success or failure. It is a symbol of destiny. The cornucopia symbolizes the fruits of well-performed efforts. The clipper ship used in this plate witnesses to the owner's love of the sea: the dolphin is a token of joy to the sailor. The flaming torch has, in all ages, symbolized intellectual thirst, and the lyre is associated with music, even in the popular mind.

I noticed a tarpon upon the studio wall, after which I read in the plate-catalogue:

Robert H. Hills, Amesbury, Massachusetts.

Description: For the Royal Palm Tarpon Club, Fort Myers, Florida--

Membership card with a fifteen and a half pound tarpon cut into a steel plate

Description: For the Royal Palm Tarpon Club, Fort Myers, Florida--

Membership card with a fifteen and a half pound tarpon cut into a steel plate

The armorial designs of the Boston artist are every bit as convincing as those of George W. Eve, R.E.

There are five types of engraved bookplates:

The wood plates are engraved upon a block of wood.

The zinc-line plate is photo-engraved from a pen-and-ink-drawing, in relief. These are common because there are many designers working in this medium.

The intaglio engraving reverses the zinc-line process. The drawing is photographed on a plate and then etched in.

Photogravure probably reached its zenith in the bookplate work of Elisha Bird of New York.

Steel engraving is rarely used in the making of bookplates, due largely to the fact that the English craftsmen preferred a softer metal. Copper-plate engraving is the most difficult but also the most lovely of all of the bookplate methods: it is no small honor to be one of the five existing copper-plate engravers in the entire country.

The wood plates are engraved upon a block of wood.

The zinc-line plate is photo-engraved from a pen-and-ink-drawing, in relief. These are common because there are many designers working in this medium.

The intaglio engraving reverses the zinc-line process. The drawing is photographed on a plate and then etched in.

Photogravure probably reached its zenith in the bookplate work of Elisha Bird of New York.

Steel engraving is rarely used in the making of bookplates, due largely to the fact that the English craftsmen preferred a softer metal. Copper-plate engraving is the most difficult but also the most lovely of all of the bookplate methods: it is no small honor to be one of the five existing copper-plate engravers in the entire country.

It is easy to make facetious remarks about "the Bluebloods versus the Newbloods," but any person with an ounce of knowledge of biology in general and of heredity in particular, knows that "blood tells." A certain famous gentleman never tired of ridiculing the searchers of genealogical records with the words, " I once knew a man who climbed his family tree and found a horse thief." Were that same man to have purchased a dog or a saddle-horse he would have insisted upon a good pedigree. One is not necessarily a snob who takes pride in his ancestors. Life, like a fine painting, is given new beauty and significance by a good background. The use of one's family crest as a bookplate reveals true pride in one's past and thankfulness for those who gave us the joyful experience of living. Surely, an armorial design is a most appropriate bookplate. One's books are his choicest possessions; they are more, they are his chosen friends. The authors upon one's library shelves are the persons whom the reader has adopted into his private family; therefore, a family-crest bookplate witnesses to the fact that the chosen author is from henceforth one of the book-lover's own family. It is a symbol, a ritualistic act.

Recently a friend of the author of this sketch presented him with a thin volume from the Yale University Press, bound in Harvard crimson. More interesting than the contents of the book is the bookplate of a famous gentleman. The foreground of the plate shows a section of a library. The library door is open revealing a country lane, bordered by a church and a home, and culminating in an uplifting distant peak. Over the study door are these words:

THIS IS THE BOOK OF CHARLES

LEWIS SLATTERY:

A HAPPY PARSON

John Elwell bookplatek

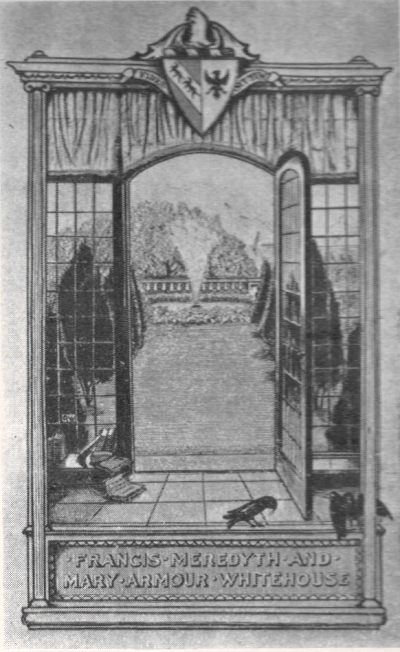

Francis Meredyth and Mary Armour Whitehouse bookplate

Who could not guess the fondness of Francis Meredyth and Mary Armour Whitehouse for nature, and for Manchester, by looking at the bookplate designed by Robert Strong Woodward and engraved by Mr. Elwell? It is a garden scene: beyond the evergreen trees and the fountain, Manchester Bay glints through a casement doorway. The armorial embellishment is inscribed: "fides scutum."

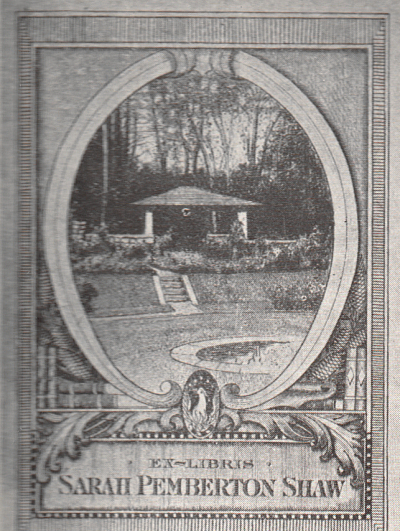

Sarah Pemberton Shaw bookplatek

The bookplate is a reminder of ownership. In mediaeval Europe the family coat-of-arms was carved in stone over the front door, engraved on the family silver, and carved upon the furniture. It was not necessary to add a name when every person of importance possessed a knowledge of heraldry. Up to 1720, simple armorial plates were used to identify the ownership of books. As the heraldic interest declined, more attention was given to ornamentation. Now that books are no longer chained, it is important that we continue the use of bookplates. A bookplate blesses him who loans and him who borrows. It is an interesting commentary on life that persons who would not rob a bank, much less cheat a street-car conductor of his fare, will forget to return a borrowed book. I would gladly pay several times the monetary value of a lost book rather than lose it, especially when I have marked my favorite lines and paragraphs. A book over which one has brooded possesses a plus quality; it is one's child. A bookplate is a constant reminder to the borrower that he has been entrusted with the care of one of the loaner's favorite possessions. If one is careless about such matters, the bookplate shrieks out loud: Take me home! Take me home!"

Agnes Repplier tells us that she had access, when a little girl, to a well-chosen library, each volume of which was provided with a bookplate containing a scaly dragon guarding the apples of Hesperides, and the motto, "Honor and obligation demand the prompt return of borrowed books." She confesses that these words "ate into her innocent soul" and "lent a pang to the sweetness of possession," as she did not know the exact nature of "prompt return." Did it mean a month or a day?

A bookplate is one of the finest memorials. Harvard University has 275 varieties of bookplates to distinguish the sources of books. The British Museum possesses over two hundred thousand specimens of bookplates. A book given to a library has no other significance than its contents but, when the book contains a personal bookplate, it is a perpetual memorial to the donor. Mr. Elwell had an experience which illustrates the significance of a bookplate. A dealer in second-hand books brought a volume to the craftsman one day, asking him if he wished to purchase it. The book had no special significance and was sold for $3.50. When Mr. Elwell opened the book he discovered the bookplate of Charles Sumner. A bookplate may have personal interest, heraldic interest, genealogical or historical significance, in addition to its intrinsic artistic value, but more, it may be the finest memorial to a man's life and work. One illustration must suffice: Mr. Elwell designed and engraved a bookplate for Jeremiah Gilman Fennessey, as a birthday gift from his daughter. The center panel shows the birthplace of Mr. Fennessey in Glamworth, Ireland. The Celtic ornamentation of the border, the open book and an inscription by O'Riley, are further indications of the character of a great man. After the drawing was completed, but before the engraving of the plate, Mr. Fennessey made "the great adventure." His library has been divided between Holy Cross and Boston College. So long as students shall go into the libraries of these great colleges to open the books given in memory of Jeremiah Gilman Fennessey, they shall be reminded by his bookplate, not only of his life, but of the qualities which made his life a blessing to those who knew and loved him.

Surely Eugene Field was wise when he urges all lovers of books to provide themselves with bookplates.

The above article, retyped in digital format for use by search organs, was published in the May 1, 1931 edition of The Boston Breeze which has since gone out of business.

For more information on the home town of John Elwell, and to see an etching he made titled "The Tea Party", please click here: The Newton Highlands Archives.

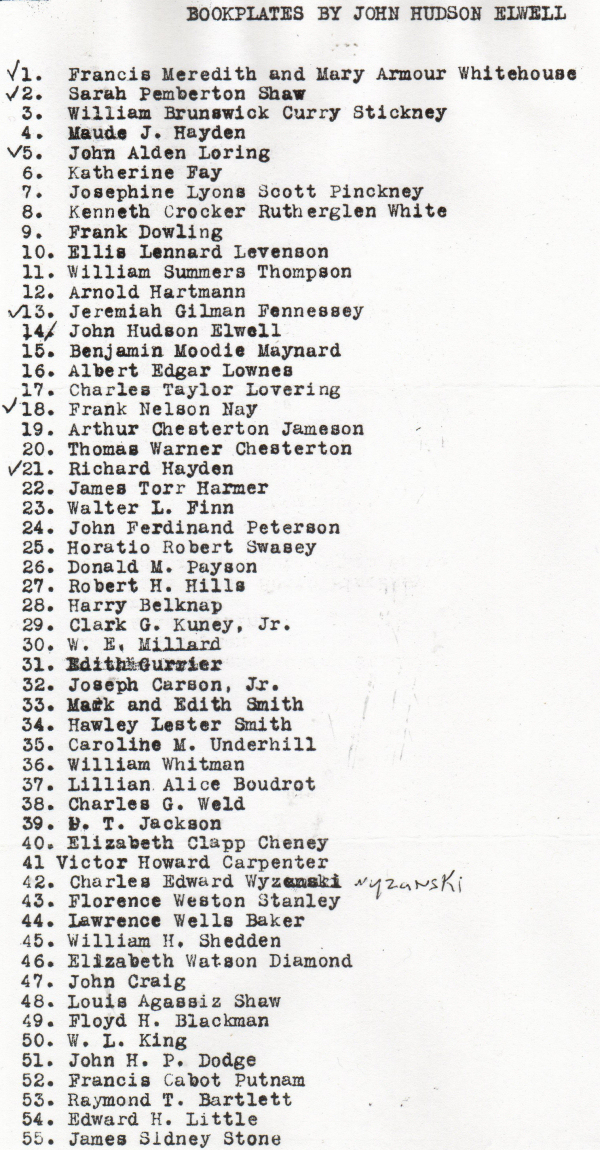

Below is a list of known bookplates made by John Hudson Elwell:

List of known Elwell bookplates

Following is biographical review of Mr. Elwell:

Biography of John Elwell

For more on bookplates click on the following websites:

http://bookplatejunkie.blogspot.com/2008/08/bookplates-for-sale-or-exchange.html

Robert Strong Woodward's Bookplates and Illuminations

There are very few articles written on "Bookplates." Following is one of them:

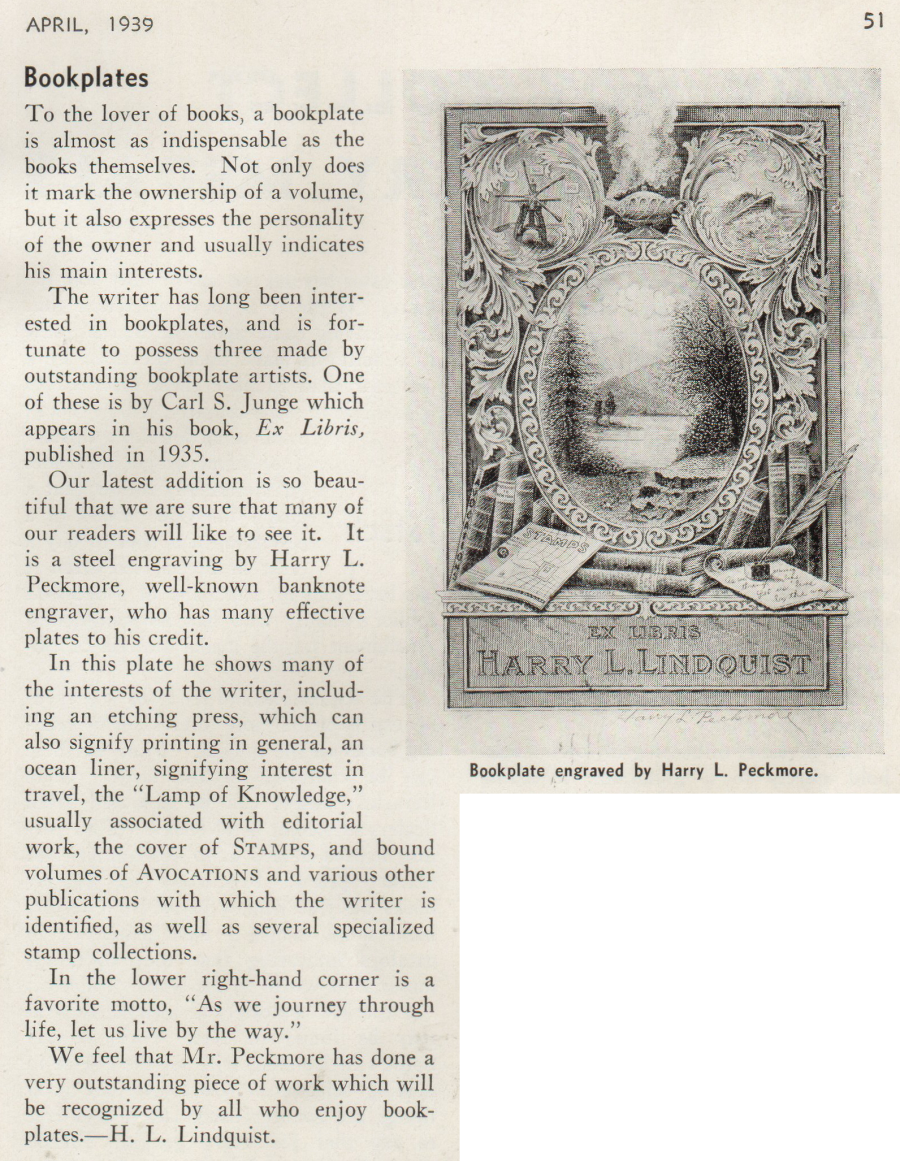

Bookplate article appeared in Avocations, A Magazine of Hobbies and Leisure, in the April 1935 edition, Vol 4 No. 1

JOHN HUDSON ELWELL

1878 - 1955

This card is a restrike from the copper-plate etching by John Hudson Elwell. The late maternal grandfather of Barbara Lee Fox Ash, Mr. Elwell was born in Marblehead, Massachusetts. His work included copper-plate bookplates, etchings on steel, engraved wedding invitations, watercolors, and pastels. John Hudson Elwell was an apprentice to Rueben Carpenter, the outstanding banknote engraver of the late nineteenth century, and he was a pupil of Vesper L. George. For many years he worked as an engraver at the W.H. Brett Company, Boston. Mr. Elwell is listed in the Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers and Who Was Who in American Art. "Jack" Elwell was married to Charlena Dennison Hoyt. They resided in Old Marblehead and Newton Highlands, Massachusetts until his death.

John Hudson Elwell gravel

John Elwell was born in 1878 and died in 1955. He was buried in the Arms Cemetery in Shelburne Falls, MA in the plot adjacent to Robert Strong Woodward. Mr. Woodward made many bookplates in his early career and sent many of them to his friend, John Elwell, in Boston to have them sketched onto copper plates for reproduction.

John Hudson Elwell must be remembered for being one of only five practicing professional bookplate engravers in the country during his lifetime.

MLP

January 2012