Ada Small Moore

Ada Small Moore (1858 - 1955) (Photo courtesy

The International Museum of the Horse Archives, Kentucky Horse Park)

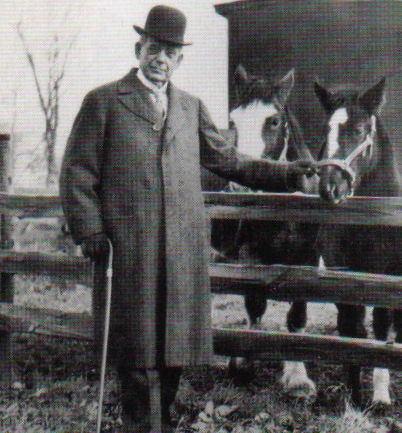

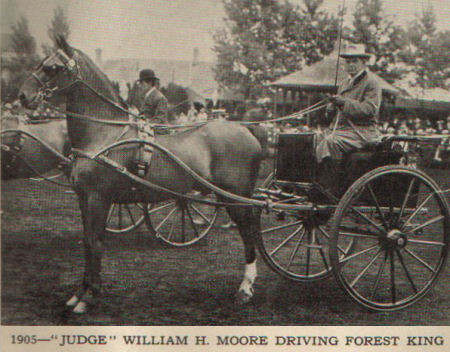

William H. Moore (Photo courtesy

The International Museum of the Horse

Archives, Kentucky Horse Park)

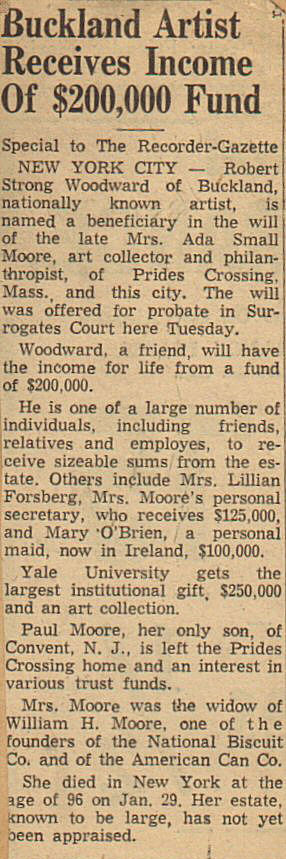

Greenfield Recorder Gazette article, 1955

Photo William H. Moore from book written by his grandson,

Archbishop Paul Moore of New York City

Moore mansion, Rockmarge, at Prides Crossing

on the Massachusetts north shore

Photo of Ada Moore on African safari

from book "Presences" by Archbishop

Paul Moore of New York City

Newspaper photograph of William H. Moore

We have very few photographs of their relationship. One newspaper article photo of her husband, William H. Moore, was found in an early scrapbook.

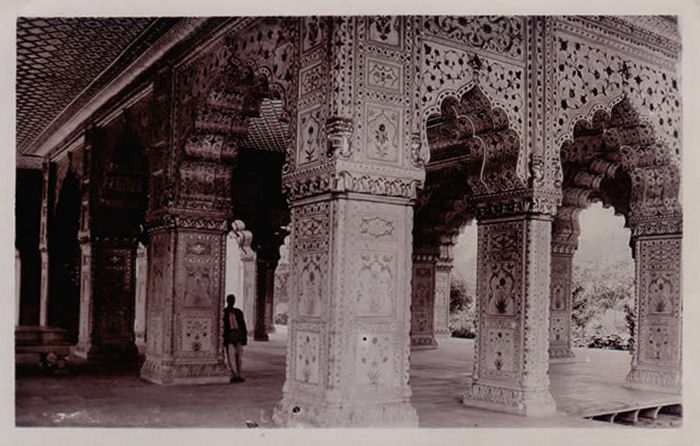

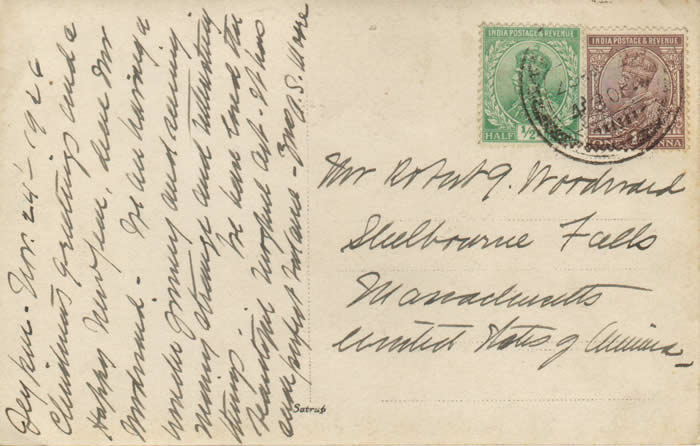

The following postcard was found in the Southwick Studio. It was written to RSW from Ada S. Moore while on a trip to India.

Ada Moore post card from from India

Jeypur (ed. note: Jaipur India). Nov. 24, 1926 Christmas Greetings and a Happy New Year, dear Mr. Woodward-

We are having a wonder journey and are seeing many strange and interesting things. We have loved the

beautiful Moghal(?) Art. It has such perfect balance. Mrs. A. S. Moore

Mrs. Ada Moore lived in a house in New York City at 4 East 54th Street.

One of the very few letters from Mrs. Moore to Robert Strong Woodward which has been found in the Southwick Studio is below. RSW was known for burning personal correspondence in his studio fireplace and it is my assumption that all of their mailings were destroyed.

Outside envelope, postmark, Prides Crossing, Mass. 1933 Oct 1933, 5 pm, 3-cent stamp

Letter typed by Mrs. Moore's personal assistant, Miss Forsberg - Tiffany stationery, letterhead:

Rockmarge

Pride's Crossing, Massachusetts

October 19, 1933

Dear Robert:

I found your letter on my return and your telegram was forwarded to me while I was in Evanston. I returned on Monday and after visiting my doctors in Boston found that my eyes were none the worse for the journey. The cause of the trouble has been removed but it may take sometime to smooth out the result. In the meantime I am very well and very busy here at Rockmarge.

I have had another sorrow in the death of my only brother who passed away last evening. He has been an invalid for many years and has wanted to go for sometime. So we cannot grieve for him, but it is another break in our happy family group and those of us who loved him will miss him.

Miss Forsberg is writing this for me and told me of her and Mrs. Jagoe's pleasant call on you at Shelburne Falls. I am glad they had the opportunity of meeting you and also glad to have direct news of you.

I am staying on here until the 30th and then shall go directly to New York.

I hope you are enjoying these beautiful days and that your faithful Fabian is back with you again.

Affectionately

[signed] Ada S. Moore

One of the very few letters from Mrs. Moore to Robert Strong Woodward which has been found in the Southwick Studio

Permission has been obtained from the Yale University Art Gallery to reproduce 19 pages from an article entitled "Ada Small Moore: Collector and Patron" by David Ake Sensabaugh and Susan B.Matheson from the Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 2002.

The text only is reproduced, not the images such as those of vases, the exteriors of museums in Greece, etc., The text has been entirely retyped in digital format so that search engines can scan and utilize it.

Permission to reprint this material here extends to July 2019.

ADA SMALL MOORE:

Collector and Patron

by

David Ake Sensabaugh

and

Susan B. Matheson

After Ada Small Moore died in January of 1955, Arthur Upham Pope, the scholar and promoter of Persian art, wrote, "Mrs. Moore's death, she was in effect our foster mother, fractured the axis on which our life has turned for thirty years." His words are indicative of the role that "Mother Moore," as she was affectionately known, played in the lives of scholars and the world of Oriental in general. Her interests were broad: her collections contained objects ranging from the ancient Near East and Mediterranean world to contemporary Chinese painting, with Islamic textiles, Luristan bronzes, Chinese bronzes and ceramics, and Japanese textiles and prints coming in between. From 1937 until her death she was the one most responsible for building a collection of Asian art at Yale. Her bequest of ancient Greek and Roman glass endowed Yale with one of the country's premier collections in this field. Her generosity to Yale extended beyond gifts of art, and her philanthropy spread beyond Yale. She donated exceptional and still prized works of medieval art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and also made gifts to other departments at the museum. Her financial support of numerous American and foreign cultural institutions, much of it given anonymously, centered on education and research in both the arts and the sciences and ranged from endowing libraries to building a museum. Now, fifty years after her death, Mrs. Moore should be recognized as one of the great unsung collectors and patrons of the first half of the twentieth century.

Ada Small Moore was born Adelia Waterman Small in 1858, the daughter of Edward Alonzo Small and Mary Caroline Roberts. In 1853 the family moved from Maine to Galena, Illinois, where Edward established his own business. In summers, they returned to Maine, where Small Point still bears the family name. Boating was a favorite pastime, and Ada often spent mornings with her father on the lake discussing the reading he had assigned her, which included such texts as Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. This early introduction to history had a profound influence on Ada's later interests. When Edward's business failed following the financial panic of 1857, he turned to law, and he was admitted to the bar in 1858. In 1869 the Smalls moved to Chicago, where Edward became a successful corporate lawyer.

In 1872 a young lawyer named William Henry Moore joined Edward Small's law firm, becoming a partner in 1877. In 1878, he and Ada were married. Upon the death of Edward Small in 1882, William invited his brother, James Hobart Moore (who had married Ada's sister, Josephine) to join as the new partner. After several years, the brothers moved from law into corporate management and finance, becoming the first and among the most successful at arranging corporate merges, among them the combination of small firms into the National Biscuit Company and American Can Company. In May 1899 a syndicate led by the Moores attempted to buy the combined Carnegie-Frick properties, and although this effort failed, the Moores were one of the four major groups in the steel industry and partners with J. P. Morgan in the founding of the United States Steel Corporation in 1901.

In 1900 Ada and William moved to New York, to a townhouse at 4 East 54th Street designed by Stanford White. Ada began acquiring art almost immediately. The family spent summers at Rockmarge, their seaside mansion in Pride's Crossing, on the north shore of Massachusetts. William's business interests now focused on railroads, and in spite of some reverses, he retired from business in 1917 an immensely wealthy man. The couple had three sons, Edward, Hobart, and Paul, all of whom attended Yale, continuing a family connection that began with the College's founding and continues today.

Although Mrs. Moore had started collecting within the first few years of the new century, much of her collecting and patronage of scholarship was stimulated by extensive travel undertaken after the death of her husband early in 1923. Almost immediately she made a trip around the world by ocean-going yacht. From that time up to the beginning of World War II she seems to have traveled abroad almost every other year, well into her seventies. Frequently in Europe, she also journeyed eastward to Greece, Egypt, Turkey, Persia, India, China, and Japan, traveling by ship, train, car, and plane at a time when travel was seldom easy and even less frequently undertaken by an elderly American widow. On one later boat trip, according to her grandson Bishop Paul Moore, she sailed up the Nile and Yangtze rivers.

During those years she became friends with Arthur Upham Pope and his wife, Dr. Phyllis Ackerman, supporting their researches on all aspects of Iranian art, including their great six-volume endeavor, A Survey of Persian Art, which was conceived after the First Persian Exhibition and Congress held in Philadelphia in 1926 and finally published in 1939. She was also a supporter of the American Institute for Persian Art and Archaeology, founded by Pope in 1928, and of its successor institutions. It was through Pope that Theodore Sizer, curator of painting at Yale, in a letter from London dated April 30, 1936, learned of the full extent of Mrs. Moore's intended gifts to Yale. Gifts of textiles and glass had been spoken of earlier in February when Sizer had gone with Pope and Ackerman to visit Mrs. Moore in New York, but Pope now wrote to Sizer that Mrs. Moore's collection of Chinese paintings was also destined for Yale. He touted the collection as "one of these very great collections that are known to relatively few but the inside 'ins.'" At that time, the International Exhibition of Chinese Art that had been held in London at the Royal Academy in late 1935 to early 1936 had just concluded. Mrs. Moore had been invited to lend some of her early Chinese paintings along with other objects to the exhibition. Knowledge of her collections of Chinese art clearly had already begun to spread beyond the world of "inside 'ins.'" Yale was excited at the news of these impending gifts. Everett V. Meeks, dean of the School of Fine Arts, wrote at the top of the letter, "Perfectly splendid!"

MRS. MOORE COLLECTS CHINESE ART

Mrs. Moore's early acquisitions of Chinese art seem to have begun shortly after she and her husband moved in 1900 to their new townhouse on East 54th Street. In 1903 Thomas B. Clarke, who in addition to being a collector and patron of contemporary American art and artists was also a collector and dealer of Chinese porcelain, sent her a description of a small Kangxi period (1662-1722) amphora-shaped porcelain jar with a peach bloom glaze that was in her collection. She had presumably purchased the jar from Clarke, who was anxious for her to know what she had acquired and that she was in the company of, among others, H. O. Havemeyer, Benjamin Altman, and Henry Sampson in New York; Harry Walters in Baltimore; Peter and Joseph Widener in Elkins, Pennsylvania; and George Warren in Troy, New York. This is one of the few clues to the direction of her early collecting. For other collectors of the time, including Henry Clay Frick and J. P. Morgan, Chinese porcelains of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were necessary adjuncts to the collecting of Old Master paintings. For Mrs. Moore they seem to have been the beginning of an interest in East Asian art. Over the next decade she continued to buy porcelains from Clarke, Rufus E. Moore (1840-1918), Dreicer and Company, and others. In 1913 she purchased another monochrome porcelain and a jade zodiac disc from the auction of the collection of the Manchu Prince Kung [Gong] that had been arranged by Yamanaka & Company and held at the American Art Association. Gradually, however, she expanded her collecting to include less fashionable and more specialized areas of Chinese art. By the early 1920s she had already begun to assemble a collection of Chinese bronzes and paintings. She bought from the Japanese firm Yamanaka & Company, already well known in New York, and from the Paris-based Chinese dealers Ton-ying & Company and C. T. Loo & Cie., who established themselves in New York during World War I.

In 1918 Mrs. Moore acquired what was thought to be an early Shang dynasty jue ritual vessel from A. W. Bahr sold through N. E. Montross in New York. The choice of this jue was remarkable because it was one of the most archaic shapes then known and was unlike anything else available. It proved to be even more remarkable when in the 1940s it was examined at Columbia University and appeared not to be bronze. Subsequent analysis of the metal showed that it is made of a silver alloy and that it was not cast in piece molds---the technology typical for the Shang period---indicating that it is probably an archaistic piece from a later period. In 1918, however, it provided an ideal starting point for Mrs. Moore. In 1924, after the publication of Bronzes Antiques de la Chine appartenànt a C. T. Loo et Cie., she acquired two important Zhoudynasty gui vessels, one of them with a lengthy inscription, from Loo. Two years later she followed these purchases with the acquisition of an owl-shaped zun, also bought through C. T. Loo. This vessel, like the jue proved to be controversial. Thought by some to be an archaistic work of the Song dynasty (960-1279), it was examined and tested at the Freer Gallery of Art and shown to be a work of the Shang dynasty (16th-11th century B.C.E.). In 1928 she acquired another unusually shaped jue vessel with two pouring spouts and a lid. One of her last major acquisitions came in 1930 when she bought a pole top (Shang dynasty, 16th-11th century B.C.E.) with an animal and a human face on the opposite sides. This small but choice group of Chinese bronze objects, now at Yale, was the core of her collection. Some were borrowed for the International Exhibition in London and they were all borrowed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a major exhibition of Chinese bronzes held in 1938.

While Mrs. Moore was acquiring Chinese bronzes she was also wading into the more dangerous waters of the world of Chinese painting. Over the years her painting collection was to be of special interest to her. She had begun to collect as early as December of 1914, when she acquired two paintings from the collection of the longtime resident of China, John C. Ferguson. There had been an exhibition of Chinese painting held at the Metropolitan that year with a catalogue by Dr. Ferguson, who had been acquiring paintings in China for the Metropolitan. The exhibition may have been the inspiration for her to move in this direction. Over the next two decades she added many scrolls, believed at the time to date to the Tang (618-907), Song (960-1279), and Yuan (1279-1368) dynasties. Among her early purchases was a large hanging scroll considered to be by Mi Fu (1051-1107), which she acquired in 1917 from C. T. Loo, and another large scroll attributed to Ma Yuan (active ca. 1189-1225), also purchased in 1917, that came from the Shanghai collector Pang Yuanqi. It is possible that she acquired the two eleventh-century images of Zhu Guan and Du Yan, two of the "Five Old Men of Suiyang," at the same time, since C.T. Loo had put them on the market through his newly established Lai-Yuan & Co. in 1916. She continued to buy from C. T. Loo and from Yamanaka, but she seems to have established a particular rapport with Ton-ying & Company. From Ton-ying she acquired scrolls associated with many great names in Chinese painting: Yang Sheng (active first half of the eighth century), Li Gonglin (ca. 1041-1106), Mi Youren (1075-1151), Zheng Sixiao (1241-1318), Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), and Wang Mian (1287-1359).

Ton-ying & Company in New York was represented by C. F. Yau (Yau Chang-foo; Yao Shulai), who, between Mrs. Moore's travels, recommended paintings to her and helped in researching the paintings that she acquired from him. His English was quite good, and his ease with the language plus his depth of knowledge may have facilitated the close relationship that they seem to have formed. C. F. Yau was a classically trained scholar whose father had been an official in the Qing government and who himself had taken a degree in the last imperial examinations in 1905. He had joined Ton-ying & Company shortly after its New York branch was established, bringing his scholarly background to the antique business. In her collecting of Chinese paintings, Mrs. Moore also seems to have relied on Louise Wallace Hackney, who may in fact have served as a de facto curator for her. Miss Hackney had studied Chinese painting in the United States and in Europe and had gone to China to make a special study of painters' techniques. She published a book on Chinese painting, Guide-Posts to Chinese Painting, which she dedicated to Mrs. Moore, and she lectured at both Columbia and Oxford universities. It would be to Louise Wallace Hackney and C. F. Yau that Mrs. Moore would turn when a scholarly catalogue of her collection seemed appropriate. The catalogue was published as A Study of Chinese Paintings in the Collection of Ada Small Moore.

By the 1930s Mrs. Moore's collection was beginning to be known. The International Exhibition of Chinese Art, mentioned earlier, was held at the Royal Academy of Arts in London from November 1935 to March of 1936. The exhibition itself was a watershed in the study of Chinese art in the West. It included for the first time objects from the Qing imperial collections that came on loan from the Chinese government and were transported by a British battleship especially for the exhibition. As mentioned above, Mrs. Moore was among the private collectors asked to lend both bronzes and paintings. Among her paintings was a landscape hand-scroll thought to be by emperor Huizong (r. 1101-25) that she had acquired from the collection of Pang Yuanqi of Shanghai in 1925 through Ton-ying & Company in New York. This painting was to be one of the main pictures displayed at a chronologically significant point in the exhibition, but when the Boston Museum of Fine Arts declined to lend its important early handscroll Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk, considered to be Emperor Huizong's copy after the Tang dynasty master Zhang Xuan, Mrs. Moore was asked at the last minute to lend her painting A Group of Court Ladies Fatigued by Embroidering, which she had acquired from A. W. Bahr in 1923. Her painting was thought to be a Song dynasty copy of a Tang painting. It arrived two days before the Press View and was installed in place of the landscape. Percival David, the director of the exhibition, was delighted to have an important tradition of early figure painting represented in the exhibition and made the decision to substitute one scroll for the other. Mrs. Moore had also loaned a hand-scroll of bird and flower subjects attributed to the tenth-century painter Huang Quan that she had acquired directly from Yamanaka in Osaka in 1932 during a trip to Japan. These loans established the importance of the Moore collection and may have led to the idea of a major catalogue of her Chinese paintings. It was certainly knowledge of these loans that allowed Arthur Upham Pope to expound on the significance of the proposed gift to Yale in his 1936 letter to Theodore Sizer.

About 1937 Louise Wallace Hackney and C. F. Yau began to compile their catalogue of Mrs. Moore's paintings. The catalogue, mentioned above, was published sumptuously in imperial folio by Oxford University Press in 1940. It was a landmark catalogue for its time. All of the paintings were illustrated, and it included translations of all of the seals and colophons along with an essay on seals and photographic reproductions of them in addition to an index with Chinese characters.

In a laudatory review of the catalogue in The Connoisseur, H. Granville Fell, the journal's editor, also praised the collection itself: "Mrs. Moore started her collection some thirty years ago. By now it is one of the most remarkable in existence." Fell's view reflected that of his contemporary scholars, dealers, and collectors, including Charles Lang Freer, who had visited Mrs. Moore and her collection early on in her house. Reviews, even in the European press, of the Yale exhibition of Chinese painting from Mrs. Moore's collection that celebrated the publication of the catalogue emphasized both the breadth and the quality of the collection: "It is possible from the wide range of material included [in the exhibition] to get a cross section of Chinese painting from the 9th to the 15th century, through the study of examples each one of which is a masterpiece." Respect for Mrs. Moore's collection survived her. In the New York Times review of the exhibition at Yale commemorating her life and honoring her bequest of her collection to the Gallery, Stuart Preston declared, "The collection of Near Eastern and Far Eastern art formed by the late Mrs. Moore has long been known to admiring scholars. Its recent establishment at the Yale University Art Gallery --- a bequest in memory of her sons Hobart and Edward Small Moore ---at once makes New Haven a pilgrimage spot for the Orientalist, the connoisseur and the lover of art, for Mrs. Moore's generosity as a benefactor was matched by an unusual refinement of judgment." Years later, in the exhibition catalogue A Communion of Scholars: Chinese Art at Yale, Mary Gardner Neill, the exhibition curator, stated, "One has only to scan the pages of this catalogue to realize how central the Hobart and Edward Small Moore Collection is to Yale's holdings of Chinese art. Students --- past, present, and future --- will be forever indebted to Ada Small Moore and the Moore family."

MRS. MOORE AND THE ARTS OF ASIA

Meanwhile, Mrs. Moore had been active in other areas of Asian art. She had early on purchased some Persian embroidery and pottery, and she appears to have regularly purchased Chinese and other textiles on her many foreign trips. Her friendship with Pope and his wife, Dr. Phyllis Ackerman, led her to collect more actively in Persian textiles. Ackerman, who was a textile historian, seems to have guided Mrs. Moore's purchases, recommending pieces for her consideration. After she had decided to give her textile collection to Yale, perhaps in order to help finance the further researches of her friends Ackerman and Pope, Mrs. Moore in 1936 acquired the Ackerman-Pope collection. This collection became a major part of her initial gift of more than one thousand Asian and Near Eastern textiles to Yale in 1937. The gift was made in memory of her eldest son, Hobart, who had graduated from Yale in 1900 and died four years later. The name of the collection was changed in 1953 to the Hobart and Edward Small Moore Memorial Collection, in memory of her second son, who died in 1948. Mrs. Moore continued to donate objects to this collection until her death in 1955. Her bequest, encompassing both Asian and ancient Mediterranean works, became part of this collection as well.

The Near Eastern textiles included in the gift ranged from a Sasanian tapestry fragment of the sixth to eighth centuries to many fragments of sixteenth-to nineteenth-century Persian textiles. There were also Coptic textiles that had been a part of the Ackerman-Pope collection; eighteenth-and nineteenth-century Turkish textiles; seventeenth-to nineteenth-century Indian textiles; nineteenth-century Indonesian textiles; and some Japanese textiles, including an important painted gauze fragment dating to the twelfth century. Another important early piece was a fragment representing the Indian goddess Sri Maha-devi obtained by Albert von LeCoq at Bezeklik in Chinese Turkistan. Mrs. Moore added to this collection again in 1938 and 1939 and continued to augment it until her death. One very important addition came in 1951 when she acquired, then donated, the Keane Collection of Japanese priest's robes.

Mrs. Moore's smaller collection of Near Eastern and Islamic ceramics was given in 1951. Although she had made acquisitions in this field as early as 1901, the formation of this collection, too, was presumably guided in part by Arthur Upham Pope and Phyllis Ackerman. It spanned the Abbasid (749 - 1258) to Safavid (1501 - 1732) periods, including an important Abbasid earthenware bowl painted with cobalt blue and copper green that they had illustrated in color in A Survey of Persian Art.

THE ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN

Mrs. Moore's primary passion was clearly for Asian and especially Chinese art, but inspired by her travels in the eastern Mediterranean, she also assembled focused and important collections of glass and seals from this region. Mrs. Moore apparently began collecting ancient Graeco-Roman and Near Eastern glass in 1901, when she purchased a "Phoenician" glass bowl and bottle from the New York dealer Dikran Kelekian. This is the first receipt for a purchase that we have. Over the next half century, buying from New York dealers and on her travels abroad, she built one of the best and most comprehensive private collections of ancient glass in America. Of her glass collection, D. B. Harden, a pioneering scholar in the field and later a keeper in the British Museum wrote, "that extraordinary collection with lots of magnificent pieces that simply do not exist elsewhere."

Mrs. Moore was among the first to collect in this field. Most of the early collections were European, among them several nineteeth-century British collections that were donated to the British Museum, and in the early twentieth century, the Gréau, de Clerq, Sangiorgi, Niessen, and von Gans collections in Paris, Milan, Cologne, and The Hague. Mrs. Moore's records show one piece from the Sangiorgi collection, an Egyptian New Kingdom head of a vulture. Two of her most important pieces, a mold-blown beaker with Dionysos and revelers and a gilded beaker with a drinking inscription (the so-called Damascus Beaker), were originally part of the von Gans collection.

The earliest major American collection was that of Charles Caryl Coleman, an American artist resident in Italy who collected in Rome in the 1870s and '80s. Coleman purchased largely fragments, emphasizing the luxurious cameo and millefiore glass techniques that were also favored by the contemporary Italian glassmakers whose work was popular among American tourists. Between 1900 and his death in 1915, Thomas E. Hulse Curtis assembled a massive collection, incorporating some 2,400 complete vessels and 2,500 fragments, the latter mostly from the Coleman collection, which Curtis acquired en masse. The Curtis collection was purchased in turn by Edward Drummond Libbey as part of his campaign to create a comprehensive glass collection for the Toledo Museum of Art.

Other American collections were being formed at the same time as Mrs. Moore's, but they were either acquired en masse or were much smaller in scope. Some of these collectors were the wealthy industrial magnates now well known for their collections of paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts. J. Pierpont Morgan acquired the Gréau and Charvet collections, and subsequently donated both to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., also collected glass. His collection was broken up in the 1930s, with several pieces bought by Robert Lehman, a Yale graduate, and given to the Yale Art Gallery in 1953. Among the Rockefeller/Lehman objects is Yale's head flask of Livia, acquired by Rockefeller from the Duveen Brothers. The Leland Stanford, Jr., collection included a mold-mate to the Rockefeller-Lehman-Yale head flask of Livia, now in the Stanford University collection. Charles Lang Freer acquired a collection of 1,388 pieces of ancient Egyptian glass from Giovanni Dattari in 1909, the basis of the collection now at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington. Less well known is Eugene Schaefer, whose collection is now in the Newark Art Museum, a gift in 1950. Schaefer began his collection in 1920 by buying about forty pieces of Syrian and Cologne glass from a fellow German, Hermann Balz. A few of the pieces from Cologne had previously been in the Niessen collection there. Schaefer added to the collection through purchase from many of the New York dealers from whom Mrs. Moore bought, as well as through purchase at auction, something that Mrs. Moore apparently rarely did.

Mrs. Moore's goal seems to have been to build an encyclopedic collection, with examples of each of the major ancient glass-making techniques. Her collection thus included not only a wide range of simple blown vessels but also examples of mold-blown, cast, mosaic, color-band, core-formed, painted, splash, and wheel-cut glass. Her focus on technique was consistent with that of other early collectors. Unlike collectors of Greek vases, for example, for whom drawing style or a mythological subject were the likely reasons for choosing a particular vase, collectors of ancient glass concentrated on the material itself. Russell Sturgis, a prominent late nineteenth-century architect and the first cataloguer of the Jarves collection of early Italian paintings at Yale, wrote, "The enthusiastic vitreologist collects glass as glass, loving its substance and its surface, its color and its texture, its translucency and its opacity, its set patterns and its vague cloudings; here and there a stamped or wheel ground pattern adds to its own attractiveness, but the glass itself is the thing! Precious and beautiful is glass, even in fragments." Sturgis was writing about C. C. Coleman, whose collection, mentioned above, included thousands of fragments. The article was published in 1894 in the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine---a popular magazine featuring travel memoirs, poetry, profiles of artists and collectors, and serialized novels---demonstrating the growing popular appeal of ancient glass as a focus for collecting. Louis Comfort Tiffany owned pieces of ancient glass---several were found in his studio after his death---and they inspired a line of vessels reproducing actual ancient shapes and many other creations imitating the iridescent weathered surface so characteristic of ancient glass.

Mrs. Moore responded readily to offers of the best quality pieces, buying a mold-blown cup signed by Ennion, arguably the greatest of the ancient glassmakers. A vessel signed by Jason, a bottle in the shape of the Greek goddess Tyche, a large mold-blown beaker bearing figures of the seasons, a large millefiori glass bowl, and a plate of the same technique, a painted glass kantharos, a flask in the shape of a bunch of grapes, and a small Egyptian glass inlay of the Amarna period (ca. 1400-1350 B.C.E.) depicting a princess are among her finest pieces. She was persuaded to buy expensive examples of some of the most luxurious techniques, such as cameo glass, gold glass, and painted gold glass medallions, to complete her collection; only later, with the development of archaeologically based scholarship in the field, was it determined that these were modern re-creations.

It seems likely that Mrs. Moore chose to form a collection that represented the history of ancient glass not only for her own interest, but also because it would be of value to scholarship and teaching. Her intention that her collection should be given to Yale is documented as early as 1936, although it did not come to the Gallery until after her death in 1955. She lent objects from her collection to major exhibitions on Roman art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Augustan Art, 1939; Bicentennial of the Discovery of Pompeii, 1948.) Most significantly, her collection was the focus of the first comprehensive history of ancient glass published in English and in the United States. This book, Ancient Glass, by Gustavus A. Eisen, was a lavishly produced, heavily illustrated two-volume work, published in 1922. The vast majority of the illustrations, many in color, are of objects owned by Mrs. Moore. Mrs. Moore became acquainted with Eisen through one of the dealers from whom she regularly bought glass, Kouchakji Frères, for whom Eisen wrote descriptions of objects being offered for sale. Several of these are in the Art Gallery's archives of the Moore collection, along with correspondence between the expert and the collector/patron, indicating a cordial relationship. Eisen was assisted in the book by Fahim Kouchakji, son of one of the Frères. Fahim Kouchakji was best known as the source of the Chalice of Antioch, published in 1923 by Eisen and now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Fahim Kouchakji subsequently became a dealer in his own right, and he was Mrs. Moore's primary source for glass in the 1930s and '40s.

Two other important Mediterranean antiquities came to the Gallery as gifts of Mrs. Moore. In 1952 she donated a fine Etruscan mirror of the third century B.C.E., showing the Dioskouroi, the first mirror to enter the collection and still one of the few pieces of Etruscan art at Yale. Her bequest included an Athenian vase dating from the fifth century B.C.E., a white-ground black figure lekythos by the Beldam Painter showing a groom unharnessing a four-horse chariot. The vase, first published in 1893 and part of the collection of the Polytechneion in Athens, was given to Mrs. Moore by the Greek government in 1934, an unusual if not unique provenance for a Greek antiquity in an American collection. The gift was made to her in thanks for what was undoubtedly a unique gift: Mrs. Moore had donated the funds for the new museum at Corinth, dedicated in the same year.

The excavations at the ancient city of Corinth have been conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens since 1895. Mrs. Moore had become involved with the School, probably through her acquaintance with Edward Capps, the chairman of the managing committee and a fellow New Yorker, as early as 1925, when she made the first of several donations of funds in support of the School's programs, building projects, and excavations. In 1930 Capps approached her about the need for a new museum at Corinth, and she generously agreed to give $40,000 for the erection of the museum and an additional $10,000 for endowment to cover its maintenance. The architect for the new museum was W. Stuart Thompson. Capps records that while Mrs. Moore agreed that the functional arrangement of the interior of the museum was the most important consideration, she was particularly concerned, having visited the Corinth excavations before, that the museum be sited properly so that it would offer impressive views. A thoughtful and attentive donor, as Capps relates, "she gave not on impulse but because of her deep interest in our excavations at Corinth and as an expression of her great satisfaction in what has been accomplished there in recent years."

At Mrs. Moore's request, the museum was named in honor of her father, Edward Alonzo Small. It was he who had introduced her to the Classical world when she was a child, and the museum at this largely Roman site was a fitting memorial to him and his powerful influence on her life. A plaque records her endowment and the dedication to her father.

Mrs. Moore attended the dedication of the museum in 1934. The prime minister of Greece and his wife, the minister of education, members of the Greek archaeological service, and many other distinguished guests attended, along with townspeople and school children of Old Corinth. As described by Richard Stillwell, the director of the American School, the Metropolitan (the Greek Orthodox Bishop) of Corinth first blessed the museum. Mrs. Moore was introduced, and she presented the keys to the museum to the director of the school, who in turn presented them to the prime minister, thus giving the museum to Greece. The prime minister concluded by decorating Mrs. Moore with the Great Cross of the Savior, an extraordinary token of recognition for Greece to bestow upon a foreign woman. According to the school's director, "she expressed her thanks very well and warmly." Finally, a government representative presented her with the ancient Greek lekythos mentioned above and the president of the village of Old Corinth made her an honorary citizen. A reception (American, not Greek food, to the distress of the local workmen) and a tour of the museum followed. Mrs. Moore described her impressions in a letter to Richard Stillwell written after her return to America: "I have a very definite picture in my mind and appreciate very much the chronological arrangement of the different objects, making it a real study museum, which of course, is what we wished. I have come back with a very happy feeling of satisfaction in it."

The Corinth museum included not only galleries and storage space for the finds, but also a library and study rooms. The success of the excavations, however, meant that by 1938 a substantial addition was needed, and once again Mrs. Moore came forward, giving $10,000 for this purpose. Construction was delayed by the war but finally began in 1950, by which time her original gift was no longer adequate. Still game, she donated the additional $30,000 needed, and work was completed by the end of the year. A new installation combining the old and new gallery spaces was opened in 1953, this time without ceremony.

Mrs. Moore's attention was also captured by a major campaign in the 1930s and '40s to uncover and clean the mosaics in the world-renowned Byzantine church of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Here in the mosaics of Justinian's great church was one of the most splendid uses of glass from the ancient or Byzantine world. Covered with plaster and whitewash since the church's conversion into a mosque after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, although temporarily uncovered and restored in 1848-49 by Gaspare and Giuseppe Fossati, the mosaics had remained essentially hidden from view for nearly five hundred years. When Hagia Sophia was deconsecrated as a mosque and opened as a museum by Kemal Atatürk in 1931, the Byzantine Institute of America was given permission to reveal and clean the mosaics.

Thomas Whittemore, founder and president of the Byzantine Institute, and Mrs. Moore were friends, and it was no doubt through this friendship that she was inspired to support the mosaic project, joining many members of America's cultural elite. Mrs. Moore visited Istanbul in April 1934, and she would not have failed to look in on the Institute's work. Whittemore accompanied Mrs. Moore and her party from Istanbul to Athens at the end of this visit, so that he might be present at the dedication of the Corinth Museum. In 1939, a letter of introduction from Mrs. Moore to Whittemore in hand, her daughter-in-law, Fanny Hanna Moore (Mrs. Paul Moore, another important figure in the Yale Art Gallery's history) and grandson, Paul, Jr. (then a ten-year-old-boy, later archbishop of New York) visited Hagia Sophia and climbed up onto the scaffolding with Whittemore to examine the work at close hand. The Institute's work was celebrated with the exhibition The Mosaics of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1944, shown simultaneously with The Arts under the Turkish Republic, under the joint auspices of the Institute, the Metropolitan Museum, and the Municipal Art Society of New York. The mosaics were represented by plaster casts and drawings. At the opening dinner on February 29, Mrs. Moore sat at the Byzantine Institute's table. Sometime after the dinner, Mrs. Moore wrote to Whittemore "expressing her delight at the exhibition." The project in Istanbul continued until 1949.

Mrs. Moore's interest in scholarship and archaeology extended beyond Greece and Byzantium to Persia. Her interest in Persian art, driven by her friendship with Arthur Upham Pope and Phyllis Ackerman and shown in her collection of Islamic textiles, glass, and pottery (mentioned above), inspired her to contribute to the American Institute for Persian Art and Archaeology, which Pope directed, and sponsor the excavations at the palace site of Persepolis. The excavations at Persepolis, the great Persian capital of Darius and Xerxes, sacked and left in ruins by Alexander the Great in 331 B.C.E., were conducted by the Oriental Institute of Chicago and directed by Professor Ernst Herzfeld. Mrs. Moore appears to have become interested in this project through a chance shipboard encounter with the famous Egyptologist James Henry Breasted, the director of the Oriental Institute. Between 1930 and 1936 she donated $195,500 to the Institute to support the excavations and the restoration of the Achaemenid monuments at the site. Although the majority of the Institute's support came from John D. Rockefeller, it is clear that Mrs. Moore's support was critical to the Persepolis project. She visited the site at least once, in April 1934, arriving with her two sisters (Mrs. William H. Colvin and Mrs. Harry F. Knight), three maids, a travel manager (Mr. H. C. Webster), and their baggage, in three aircraft. Coincidentally, and reflecting a general interest in this site, the Yale University Art Gallery purchased a relief from the newly discovered balustrade of the palace of Darius at Persepolis in 1933, with a gift of the Associates in Fine Arts.

Mrs. Moore also sponsored the Oriental Institute's publication of her collection of ancient cylinder seals, written by Gustavus A. Eisen with the assistance of Professor Herzfeld and other members of the Institute staff. She had begun the collection on her trip to Iran in 1934. Like Eisen's history of glass, this book was intended for the scholar and nonspecialist alike, using the Moore collection to illustrate the history and religious content of such objects. These larger themes are presented in much more detail than was normal for collection catalogues at the time, in the hope of providing help for students as well as collectors.

A modern Iranian institution that benefited from Mrs. Moore's generosity was Alborz College (then called the "American College") in Teheran. Founded by American Presbyterian missionaries as a grade school in 1873, it was accredited as Alborz College, a liberal arts college chartered in the state of New York, in 1928. Mrs. Moore's donation of money to build and endow the Moore Science Hall at Alborz College, combined with her support of the Persepolis excavations, resulted in her being honored by Reza Shah Pahlavi with the Scientific Medal (the Order of Elim) in the highest degree.

Wherever she traveled in the Mediterranean and the Near East, Mrs. Moore not only looked and collected, but also supported education, scientific investigation, and the preservation of cultural monuments. Her funding of the Corinth Museum in particular embodies her dedication to these philanthropic causes. Through this and her less public contributions at Hagia Sophia and Persepolis, her legacy to the field of Mediterranean archeology is as significant as is her legacy of ancient glass to Yale. Her benefactions to Yale encompassed not only remarkable gifts of art but also financial support, not only for the Oriental department but also toward the building of the Louis I. Kahn addition to the Gallery. She was a donor who did not seek the limelight, but she was seemingly always available to sponsor quietly the institutions and endeavors in which she believed, whether through financial support or the loan of a prized Chinese bronze to a New York exhibition to aid war victims in China.

Mrs. Moore was of a generation of collectors whose motives for collecting were as diverse as their collections. Although her motives remained unstated, from the early inclusion of her glass collection in Eisen's Ancient Glass to A Study of Chinese Paintings in the Collection of Ada Small Moore, she seems to have consciously sought to make her collections the basis for scholarship. Her choice of Yale University as a repository for her varied collections went beyond "sentimental attachments," as Arthur Upham Pope mentioned to Theodore Sizer in 1936. As with others of her generation who gave generously to many institutions "their belief in private property did not extend to artistic property."

Courtesy Yale University, The Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 2002

Public institutions shared more than $900,000.00 from the estate of Mrs. Ada Small Moore, who died January 29, 1955. Mrs Moore left a gross estate of 33,035,030 and a net of $29,129,046 as was disclosed yesterday in an estate tax appraisal.

MLP

November 2011