RSW's Style: An Essay by: Henry Haff

Website editor's note:

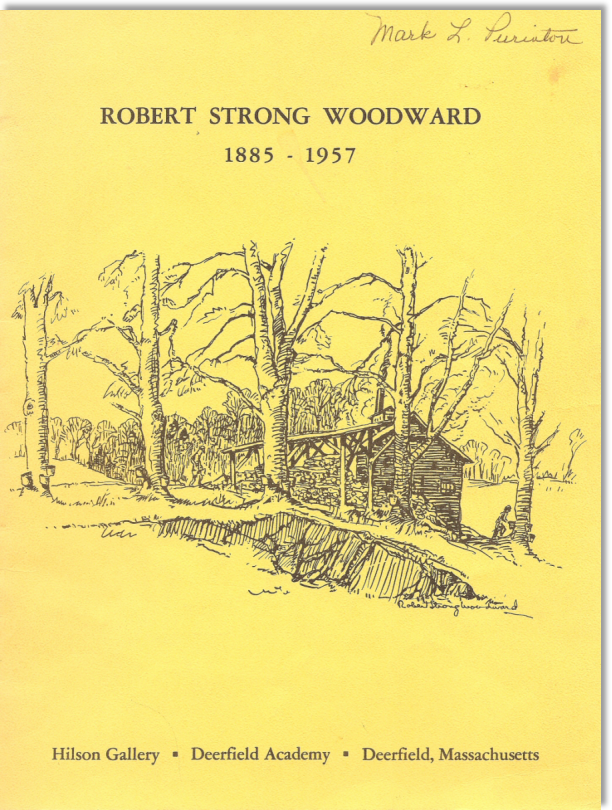

In the Spring of 1970, the Deerfield Academy's American Studies Group published what they called an

"Illustrated Catalogue" on Robert Strong Woodward to accompany an exhibit of his artwork held at the school's Hilson Gallery. The group was formed in 1963 with the expressed mission, "to carry the

study of American culture beyond the classroom," had chosen Woodward as their subject for the 1969 - 70 school year. Headed by project Chairman Garrett Hack, '70, the 15 students that made up

the group, collected, compiled, sorted and organized an impressive amount of material garnered from the likes of RSW's cousin Florence Haeberle, close friend and confidant F. Earl Williams and our

very own Dr. Mark Purinton, on their own personal time outside the rigors of their classroom study. It is an impressive program and one of the original sources for much of the initial information that

makes up this website. However, a lot of new information has come to light, particularly in the past 5 years, that proves the following essay contains a number of errors and so we have added a footnote

structure linked to an addendum section at the bottom of the page to correct these mistakes.

The following essay was written by Henry Haff, '71, and published within the catalogue. We felt

it is worthy of its own feature. Haff, only 16 or 17 at the time, made a valiant effort to summarize the essence of Woodward's style and interest in a comprehensive and insightful manner and with great

success. We hope you agree. Enjoy!

Robert Strong Woodward captured on canvas most person's feeling for New England. Its rugged simplicity surrounded him as a

boy and beckoned him to discover and understand that which so many people ignore. Part of his success might be attributed to his limiting himself to a small area and the "wealth of material in his own

back yard." As Henri Matisse said: "An American should learn his metier and work in America." Woodward's natural ability, perceptive eye and deep feeling for his native hills account for his recognition as

artist.

He was largely self-taught, spending only a few months in 1912 at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.1 Three years

later, at the age of thirty, he first took up the brush as a means of support.2 He spent that three year period at the home of his uncle and aunt in

Buckland.3 Working in his Red Gate studio there, he made illuminations, and heraldic devices, did lettering, and designed bookplates in an attempt to

help pay his living costs.

From the beginning of his painting career, he worked eagerly and persistently to develop a style all his own. He was a man of order and precision and this was reflected in

the serenity of his uncluttered studio and the logic of his work. His early paintings treated the scenes in an impressionistic manner. Brilliant colors and bold strokes were characteristic of his work at this time,

but never to the extent of the new school of Extremists. He often used very large brushes, but never a palette knife to put on thick layers of paint. At this early period of his development, his isolation and sense

of order were two important factors in determining his style and technique.

In 1918, upon the urging of Gardner Symons, an older artist in the area, Woodward sent

The Golden Barn to the National Academy Exhibit in New York City where it passed the jury and was hung. The

following year he entered Between Setting Sun and Rising Moon winning the First

Hallgarten Prize of $300.00. As he wrote later: "It was my first prize, my first prominent public notice. Mr. Hallgarten himself bought the painting from the Exhibition for $500.00, a tremendous sum to me

at that time!"

Unfortunately, many of his early paintings have either darkened or cracked because he had not learned the technique of making a painting stand up to time. He stated the specific

problems later when writing about Tangled Branches, a canvas painted in 1918-19. "I fear it has darkened

considerably because I didn't fully understand, at the time, the darkening dangers of certain driers and varnish mediums."

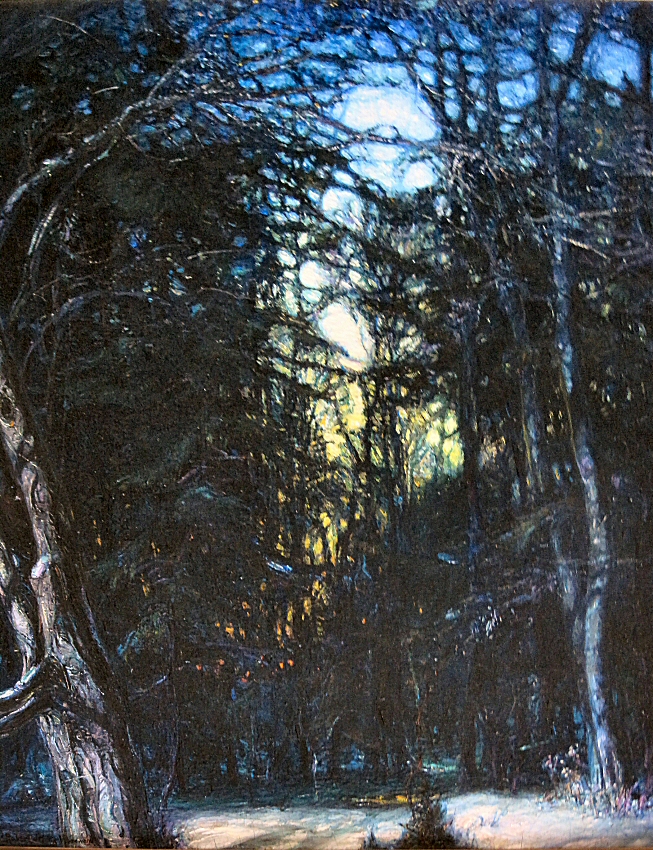

From the beginning, trees held a very important place in Woodward's re-creation of New England on canvas.

The dark forest interior with light filtering through the branches is a scene common to Between Setting

Sun and Rising Moon Tangled Branches and

Early Moonlight. Later when he had replaced his horse and buggy with a car too large to be driven down narrow roads in the dense woods, he painted fewer of the dark forest scenes.

About 1920 one critic said of his paintings: "So marked has been his progress that it is easy to take a dozen of his paintings and arrange them chronologically without a mistake."

Whether in full leaf or completely bare, the structure of a tree always fascinated Woodward. He could capture its texture and beauty from the solid shade of the trunk to the delicate pattern of new twigs. When he found a beautiful tree he often painted it several times. In Early Sugaring it is possible to see the wide variation and contrast of color and thickness of paint, which characterize his early canvases. With the years came a softening of contrasts and a greater precision in all his painting. This is evident in At Peace, a canvas of a stately bare maple on a bank fringed with other large trees. The fine texture of the last stretching twigs gives the painting a lacy quality. As his style developed, his strokes became shorter, the range of greens blended, and his eye became more sensitive to the color change of filtered sunlight. The cycle of the seasons was caught in the many paintings of the much loved beech tree near his Heath studio.

The intensity of feeling for his composition together with his masterful use of color gave his paintings of house and barn great merit. Woodward

was so fond of his barn paintings that at one time he hoped to devote an entire show to them. On occasion he would hide all of these canvases in the hope that customers would buy some of his other work. However, the

barn paintings were so popular that he was never able to accumulate enough for a show.

The rough texture of the narrow old boards on his barns and houses sing of New England. He always painted them

just as he saw them, complete with weathering stains and shadows. He often disobeyed all rules of composition by placing his buildings in the exact center of the canvas. To most landscapists of his time that would have

seemed disastrous, but Woodward had a rare talent for picking out a balanced scene with his eye and then portraying it accurately. Even the asymmetrical structure of "The Leaning Silo" could not upset this sense of

equilibrium in his painting. Never would he have to move an object from its real place in a scene to get a balanced composition.

He seldom visited an exhibition of his paintings because, as a contemporary critics wrote: "He fears that if he himself should appear at the

galleries where they are showing, a sentimental interest might be awakened in his work; and he wants no such superficial interest, but rather desires his power as an artist to be the foundation for the reputation

which he is building so rapidly."

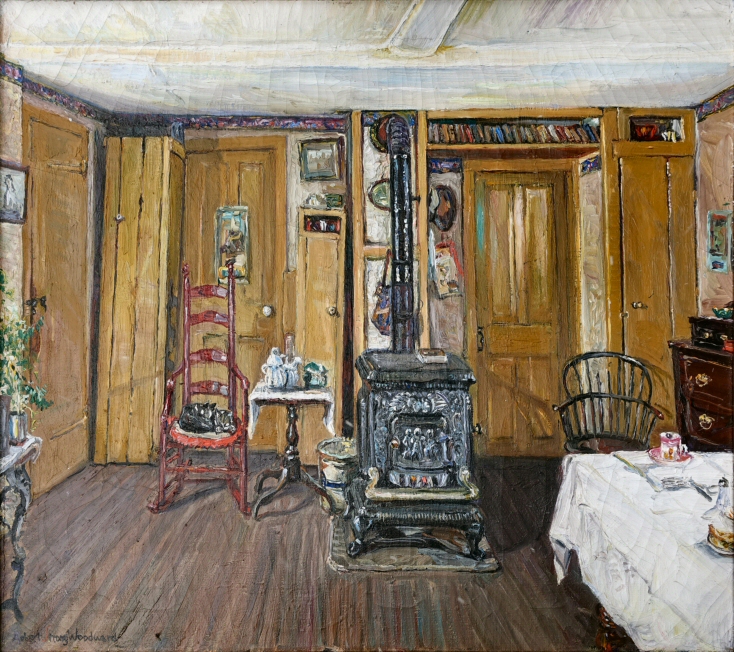

Living and working among the hills surrounding his home, Woodward was well acquainted with neighboring families. The Keaches, living up the hill from his Buckland

home, are a fine example of this. Mrs. Keach's Front Porch,

The Keach's Stove, A Country

Sitting Room and many other paintings portray the simplicity and dignity so characteristic of rustic New England. He "understood the kind of people who built the hillside farmhouses and barns, and the

winding roads which time, and wind, and rain, and snow have made picturesque."

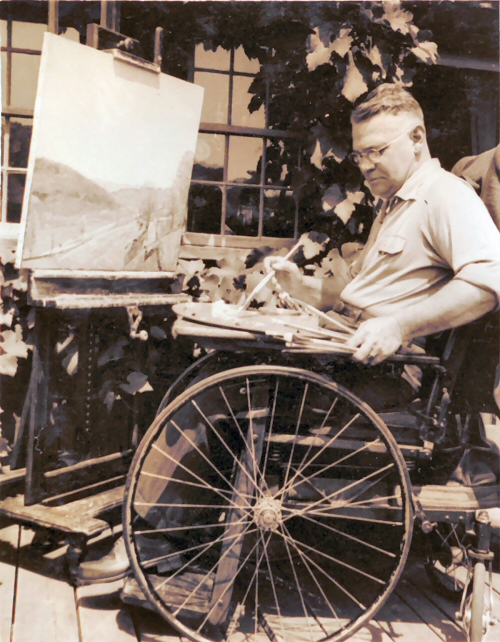

Woodward used many of the basic procedures in preparing and painting a canvas that were common to most landscapists. Often starting with a preliminary drawing in a sketchbook, he recorded his first impressions. Next came a charcoal sketch on the canvas used as guide for the pigments, which followed. He worked directly from the scene he was painting whenever possible, even during the winter, dressed in a fur coat and stocked with a day's supply of hot coffee. It usually took him four to five days to complete a canvas. He was unable to step back from a painting to observe it in perspective, and to compensate for this he learned to "unfocus" his eyes and achieve the same effect. After finishing a canvas he would sometimes give his signature a touch of variety by using red paint for the "S" in Strong.

Spring brought sap buckets, melting snow and a wealth of fresh greens to the countryside and therefore to Woodward's canvases. The well-known red buckets that hang on the maple trees throughout New England, as in "Spring Silhouette", herald a season dear to many people. Mud on the thawing roads is portrayed in a palette of browns, red, and greys but cannot overpower the new life caught in the budding twigs and brilliant blue sky. He loved to paint sugarhouses, inside and out, and the smell of boiling sap is easily imagined in the smoke rising from the chimney. Early Sugaring is a fine example of his success in capturing the atmosphere of "sugaring". In it the reconstruction of light hues and the glorious blue skies harmonize to perfection.

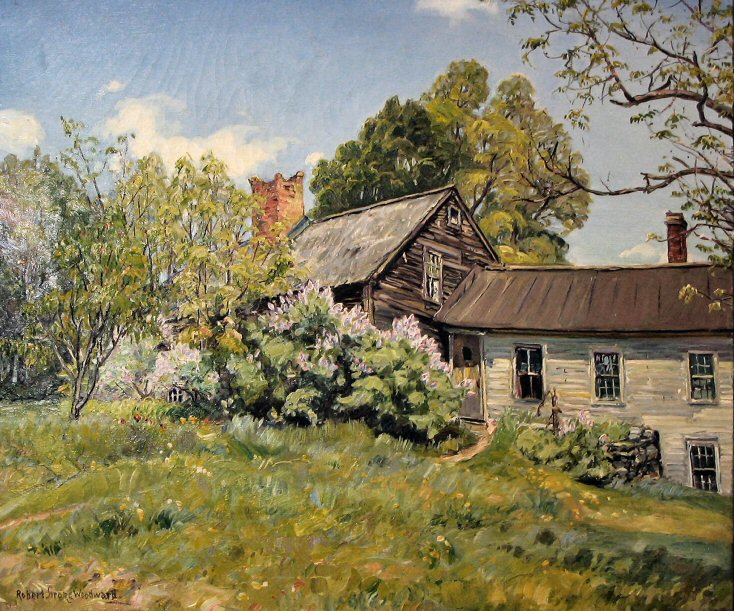

At Lilac Time is a spring painting with the season well advanced. A noticeable refining of his brush strokes in the grasses, bushes and trees of this canvas give the field inthe foreground a texture fit for the bees in the summer and the scythe in the fall. The flowering lilac bushes add the extra touch of life to the old farmhouse, which appears to have seen them so many times before. The blending of greens from olive to emerald adds a flowering laziness of canvases like Down the Hill Road and Summer Peace. Even their names suggest a broad view and awaken old memories.

The intensity of color that accompanies the fall season changed Woodward's grass to brown and his leaves to red and yellow and orange. In Maple Flame he painted the same tree as in At Peace, but this time dressed in its most vibrant suit. October Symphony and An October Pasture also employ the bright autumn colors, which find a harmony that might seem impossible with such contrasting pigments. By The Broken Wall, another fall painting, exemplifies Woodward's growing ability to portray clouds. Billowy and floating in blue, they give the picture life. In another mood, After Rain contains a low ceiling of layer after layer of clouds reaching back in the distance, a shaft of light breaking through them. The line of the horizon from the Heath studio is common to many of his canvases but each varies, usually in the clouds which take up half of the painting above the rocks and his famous beech tree. Ominous clouds rise and expand in the distance of August Horizon, an effective use of many shades of grey foretelling rain. The luminous quality of a summer storm adds a final touch.

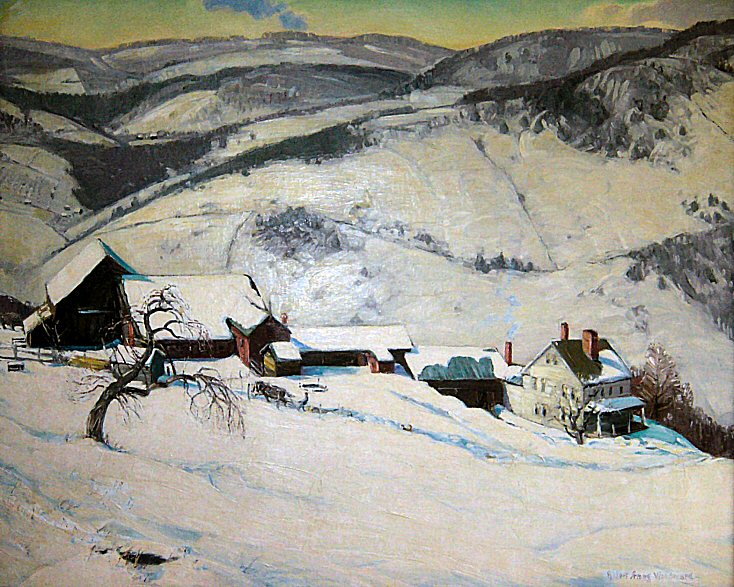

"Winter, the most difficult of all moods of Nature, depends for its interpretation on both temperament and technique to a greater degree than any other." However difficult winter may be to capture on canvas, Robert Strong Woodward saw the stark trees against sun-glistened snow as a delightful challenge. The result was a series of winter paintings of outstanding beauty. Critics have praised him especially for his success in catching the color and vigor of the winter months.

Woodward's still life and windows scenes were popular from the time he started painting them in the mid-thirties. By then his style was well developed. His attention to small detail in the foreground against a country scene beyond the window attracted many nostalgic urban buyers, for once the paintings were hung in an apartment one could look "outside" and feel New England. The shape and hand blown texture of every glass and bottle, a pot of scarlet geraniums, the page in an open book, the sunlight on a window sill, give the warm feeling of a place well loved. Through the protection of the old New England glass, the falling snow, blue icicles, lonely footprints and snow laden trees of the outside world increase the sense of warmth and shelter within. These paintings became so popular that it was common for him to have several orders waiting while he was working on another.

Woodward was meticulous about the arrangement of things in his studio. However if a petal fell from one of the geraniums, as in

Apple Tree Window, it found its place in the painting where it lay on the table. The old blown glass of each

windowpane was an integral part of this type of painting. In rebuilding his studios he insisted that, "we must be patient and we shall eventually find old glass."

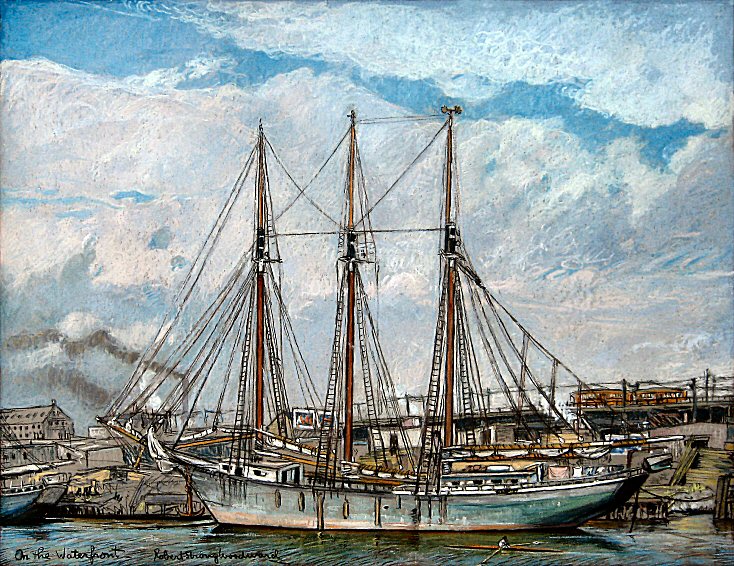

The only medium besides oil in which

Woodward worked with any frequency was chalk, and he developed a crisp, clean style and an unusual dexterity in the use of bold color. He was able to capture the same New England atmosphere in his chalks

that he did in his oils.

His only known seascapes were done in chalk. "On the Waterfront" is one of these rare subjects. In some of his earliest chalks, dampness later produced a green mold and because of this, parts of some chalks, as in "In Old Boston" were erased and done over again. This explains their occasional roughness. He learned that he must store the chalks in a dry spot. The artist often made a chalk and an oil of a certain scene, but never systematically did one before the other.

The full scope of Robert Strong Woodward's paintings appears at once broad and narrow: broad in the sense that he painted all the seasons,

and narrow because only New England is portrayed. There is no question that his paintings mean much to many; for they represent to his admirers that which they themselves love. Comparing this artist to either his

own contemporaries or to men in another era is not possible or necessary, for those who like his painting like them for very obvious reason. He was a fine draftsman, a talented colorist, and a perfectionist in his demands

on himself. He did not attempt to paint people for he could not do it to his own satisfaction. He did not attempt to alter his subject matter for he loved the land as he saw it. During the forty-two years that he painted, his

talent grew steadily for he was never satisfied. His early canvases are bolder and less serene than his later paintings.

Robert Strong Woodward was an artist who took pride in the New England that he loved,

and he did indeed "express it for the world."

Henry G. Haff '71

1970

Addendums & Clarifications

Footnote Format: Return (↩) to footnote, footnote number, source and any related links of available.| ↩ | 1. RSW boarded a train bound for Boston in the late summer of 1910 and attended the Boston Museum of Fine Arts School for only the fall semester. It is unclear if he even finished the semester. |

| ↩ | 2. Since the year is incorrect in the previous sentence, the math here is wrong. He moved to Buckland in December 1910 or January 1911. He moved into the home & farm of his Aunt Tella and Uncle Burt. |

| ↩ | 3. It is believed that RSW lived in the Pine Hill Farm residence for about 4 years. We believe he moved to the Burnham Cottage around the time his cousin Florence left for college in Ohio. Florence was the oldest daughter of the Wells and most likely the one who helped the most with RSW's care. |

| ↩ | 4. Of the Keach interior images we have and listed by Haff are not of good quality, however, A Country Interior has both the stove and a portion of the same room as A Country Sitting Room |

| ↩ | 5. Haff repeats the painting named Early Sugaring in his essay and we have already used it, so we selected the painting Spring Silhoutte because it best reflects the description given. |

| ↩ | 6. Haff names August Horizon in his essay and at this time we only have a black and white sepia image of that painting, so we selected Heath Horizon as a suitable substitute. |

| ↩ | 7. Haff does not name a particular winter painting and so we selected one of Woodward's signature paintings and "Gold Medal" award recipient at the Boston Tercenteriary Celebration, New England Drama. |

| ↩ | 8. Haff names Apple Tree Window in reference to RSW's window paintings, however, again, we only have a black and white image of that painting so we substituted When Apples are Ripe |