Robert Strong Woodward in Heath

An essay published in: "The Book of Heath Bicentennial Essays"

by Alastair George Maitland

"The Book Of Heath - Bicentennial Essays"

Robert Strong Woodward in Heath

An essay by Alastair George MaitlandPublished in "The Book of Heath Bicentennial Essays," ©1985

Reprinted here with the permission of the author, Alastair Maitland,

the editor, Susan B. Silvester, and Paideia Publishers, Ashfield, MA.

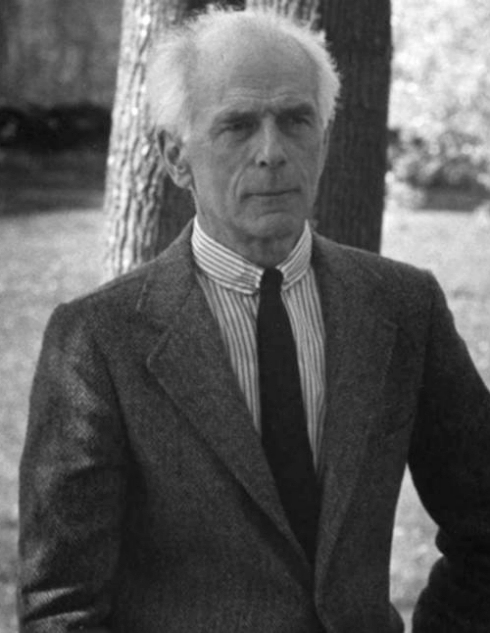

Alastair Maitland, author of essay "Robert Strong Woodward in Heath"

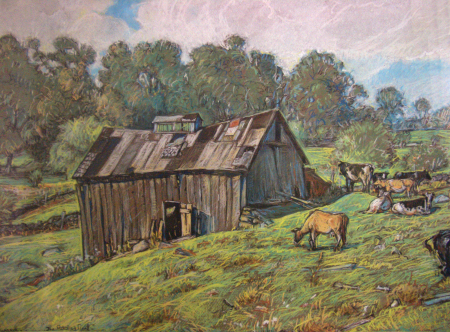

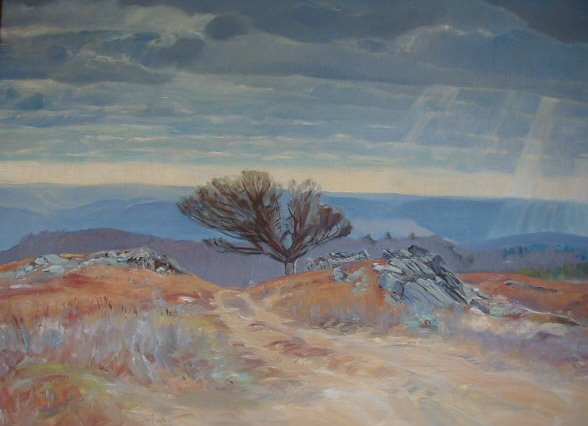

A View From Burnt Hill - an oil painting by Robert Strong Woodward

The landscape is called A View From Burnt Hill. It is the view that offered itself to the artist as he looked westward over the hills from the studio on Burnt Hill that he used from around 1936 until its destruction by fire sometime in the forties.

A View From Burnt Hill could not have been a more appropriate choice as a gift for the Heath Historical Society. If you live in Heath you don't have to love blueberries to be aware of Burnt Hill. It is something of a landmark. Within Heath's splendidly harmonious disposition of woodland and meadow it strikes a dissonant note. Moreover, although Woodward's studio no longer stands, enough of it is left to provide us with a precious, if tenuous, physical link with the artist and his work. The site is still clearly recognizable by the large slabs of ledge rock that once formed the paving stones of the terrace to the west. Beyond them, scattered over the remains of the foundation, lies the debris of the brick chimney that had buttressed the south side; and, amongst the fragments of brick and mortar, lumps of molten glass - a poignant reminder of the perfectionism that was "Woodward's hallmark." In all of his studios he insisted on "old glass" for the windows.

F. Earl Williams photograph of the Heath Pasture Studio and the beech tree

Robert Strong Woodward was by origin and birth a New Englander. He was born in Northampton, Massachusetts, on May 11, 1885, a descendant through his mother of Caleb Strong, a former Governor of the Commonwealth. There seems to be nothing in the family background to explain his artistic bent. Neither the Strongs nor the Woodwards produced painters. His father was a realtor whose business took him, and his family, to many different parts of the country. Robert's childhood was as peripatetic as that of an "Army brat." He attended at least eighteen different grammar schools and was never to develop strong roots in any single community, with one exception. His boyhood summers were spent at his grandfather's farm in Buckland. And it was there that his homing instinct was eventually to take him.

When he was ready for college the family was living in California. In 1903 Robert decided to apply for admission to study engineering at Bradley Polytechnic Institute (now Bradley University) in Peoria, Illinois. After completing his studies there he returned to California to enter Leland Stanford. Already he had developed a taste for painting, which became his favorite hobby. He was twenty-one when an event occurred that was radically to alter the course of his life and to determine its shape and content. A revolver accident resulted in years of hospitalization, complete paralysis of the lower limbs, and a lifetime necessity for a small retinue of nurses and attendants. The tragedy was also to convert a fledgling engineer into a professional illustrator and painter. The story of his life from then on is a story of immense courage and steady determination.

While in California, Woodward had been pursuing his hobby at the same time as his engineering studies. He found California "paintable to a certain extent." Not in what he called the "season," in winter when everything was fresh, but in the summer when, as he said, "everything is dried and the colors become beautiful." But as his convalescence progressed he began to feel increasingly nostalgic for his native Massachusetts, and in 1912 he returned to settle in Buckland, at the home of his uncle.

It was perhaps the hills, as much as anything, that called him back. Conway's Archibald MacLeish knew what the hills must have meant to him. "There is no lovelier place on earth than Franklin County," he said. "Nothing more human in scale and prospect than our hills." And Charlemont's Molly Scott has celebrated in words and music her love of what she calls the deep New England hills, the "hills of home," where one "breathes with the mists and the autumn rain and blooms in the springtime with the flowers again." Woodward for his part was to express the same love in his own way, with "the brush of a poet." "I can't tell you how strongly I feel about the hills," he said. "I have grown to love them so that it seems as though I had almost become a part of them. They have so much so say to me that I want to express it for the world."

Robert Strong Woodward in front of Redgate Studio

As Woodward's physical strength and self-confidence as an artist continued to grow he turned more and more to painting. Time was passing, and he saw that his illumination work was never likely to enable him to support the way of life he was condemned to live. The brush, he correctly judged, would earn him a better and a surer living than the illustrator's pen. He painted for more than a year before he showed his work to any one. Finally he summoned up enough courage to take a number of his canvases to Gardner Symons, who lived in Colrain. Symons, who had been one of the leading members of the American School of Naturalism, was sufficiently impressed to urge the young painter to send a picture to the National Academy's Annual. The Golden Barn was accepted. A year later, in 1919, a second painting, Between Setting Sun and Rising Moon, won the Academy's First Hallgarten Prize of $300, and was purchased by Julius Hallgarten himself, for what Woodward described as the "tremendous sum" of $500.00.

Chicago World's Fair poster

Acquisitions by museums and other institutions multiplied - the Springfield Art Museum, the Forbes Library in Northampton, the Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts, the Dwight Memorial Gallery of Mount Holyoke College, the Yale University Gallery of Fine Arts and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts' Spaulding Collection were amongst those to which his paintings found their way. But the bulk of his work went into private collections, including those of Robert Frost, who was to become a personal friend, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Mrs. William D. Vanderbilt, Hollywood's Jack Benny, Norman Krasna, George Burns and Beulah Bondi. (The friendship with Robert Frost was to come under a certain strain later on. Woodward records in his diary that, when Frost was poet-in-residence at Amherst College, he and his wife acquired from him a landscape in oils called Winter Dignity. It was to become Mrs. Frost's favorite painting. After her death Frost wrote to Woodward from Cambridge requesting that he take back the winter canvas and send him some other painting in exchange. Woodward comments that the transaction was one with which he was not "wholeheartedly" in agreement. But in due course the swap was effected, the other painting being Passing New England.)

RSW painting in the back of the 1936 Packard Phaeton

Robert Strong Woodward along side the Heath Pasture Studio on Burnt Hill

photo by F. Earl Williams

There has been no definitive inventory of Woodward pictures in the possession of Heath people. But in addition to those just mentioned there are three chalk landscapes owned by Helen Nichols, Alan and Catherine Nichols, and William Wolf respectively. Perhaps the largest single collection of Woodward's works is that of Dr. Purinton, of Buckland Center, a protégé of Woodward, who regarded and treated him as the son that he himself could never have had. Dr. Purinton's present combined home and office was the artist's last home-cum-studio. The studio itself has been preserved by Dr. Purinton exactly as it was in Woodward's day. An earlier studio, an ancient mill by a small stream in Buckland, which Woodward restored for his occasional use, starting in 1925, now houses the antique shop belonging to Florence Haeberle. Woodward used to refer to it jocularly as "Woodward's Folly."

Unfinished Heath Pasture Studio painting showing RSW's technique

The North Window - a painting made from

the North window of the Southwick Studio

Woodward produced few known seascapes and those that he did were rendered in chalk. And, despite the fact that his brief stint at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts had been in the life class, he only rarely, and incidentally, attempted to depict the human form, because he could not do so to his own demanding standards. And yet, one of his most appealing pictures, an early one done in 1914, contains a female figure, a rather mysterious dark-haired young woman, seated with her violoncello between her knees, alongside the text, in black lettering, of a short poem - "Cello Song" - composed by Woodward himself. This illuminated manuscript, for that is what it really is, represents but one of the many treasures adorning Florence Haeberle's charming apartment in Shelburne Falls.

An article in a Boston magazine in the early thirties described Robert Strong Woodward as "a sort of self-appointed committee of one to make certain that no season shall arrive in New England without proper recognition." But, of all the four seasons, winter was clearly his favorite. He loved winter scenes because it was in winter that he could get at the structure of the trees. Perhaps it was the engineer in him that explains his fascination with, and his exceptional gift at portraying, the skeletal forms of the trees of every sort that were a constant presence in his daily life.

New England barns came only second to trees in Woodward's roster of favorite subjects. One is reminded of Monet's classic haystack. The public appetite for his renderings of New England barns was such that at one time he thought about organizing a show of nothing but barns, if a sufficient number of pictures could have been retrieved from the individual owners. The older and more weathered the barn the better. The story is told of Woodward's visit to a farm where there was a particularly ancient barn, its sides crumbling and the rough-shingled roof near collapse. To Woodward the scene represented part of the essence of New England. He asked the owner of the farm if he might come back another day to paint a picture of the barn and surrounding fields. The owner was delighted by the artist's interest and gladly gave his consent. When Woodward returned several days later the barn had been given a fresh coat of paint. That was the end of that project. And the mystified farmer never understood Woodward's abrupt loss of interest.

In his day Woodward was sometimes compared to the landscape painters of the Barbizon School and to the American George Inness, himself an admirer of the Barbizon School, especially Daubigny and Theodore Rousseau, the trait common to all of them being that they eschewed the grandiloquent and magnified the familiar. Another comparison was with Robert Burns. Just as Burns elevated the songs of the ordinary folk of Scotland to the realm of poetry, so Woodward bestowed significance on a subject as plebeian as an isolated snow-bound farmhouse.

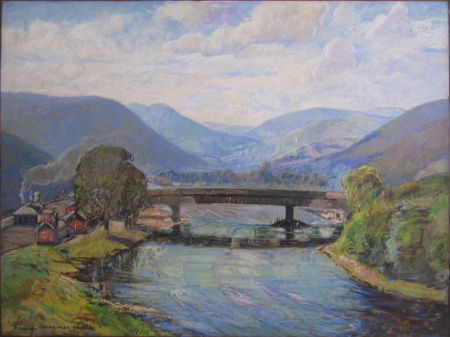

Because he was denied the freedom of movement enjoyed by others his subject matter was, of necessity, local or regional. "I live in an isolated way," he said. "And I'm not able to get at things. With me it's been local country, the local scenery I've cared for." A Springfield, Massachusetts, newspaper in 1928 reflected upon his enforced isolation and the way it had shaped and conditioned his work. He might not have become the ardent lover of his Buckland pastures, barns and bridges if he had had a wider world to range, it said. But, that condition once accepted, it gave his work "a deeper and more intimate touch than the cosmopolitan artist might possibly show." He has become the poet in paint of his own locale as Housman wrote of Shropshire and Hardy of Wessex." At the same time the paper noted that the artist as a man had remained comparatively unknown. "Unlike most exhibitors he has not been a familiar figure at local exhibitions." It was, of course, true that Woodward was "unable to get at things." But it was also true that he shrank from public appearances for fear of seeming to court sympathy.

Robert Strong Woodward may or may not have been familiar with the work of his fellow painter, George Inness, who, despite his exposure to the Barbizon School, was and remained a distinctly American artist. Inness' view, which Woodward would certainly have endorsed, was that a work of art is not to instruct, not to edify, but to awaken an emotion. "Its real greatness consists in the quality and force of this emotion." Woodward himself put it this way: "I have no patience with the so-called ultra-moderns, who defy established technical law and expression and careful craftsmanship and drawing, yet I have no sympathy with the over-studied, polished, meticulous academic painting of exact replica. The 'likeness' of a landscape, even if exact, is dead in paint unless it holds as a picture the spirit and essence and expression of the 'emotion' of it, as well as the facts - this seeming to me a more impressive, lasting and interesting thing than merely the exactly recorded fact alone." It was clearly in that emotional bond between artist and viewer that Woodward's appeal, and success, were to be found. [ See the interview by Harry Elmore Hurd ]

It is something of a paradox that Woodward, whose immense talent, despite all the odds, achieved wide recognition and brought him a measure of material success during his lifetime, should not be better known today. It can hardly be said that his name is a household word, even in Heath, or Buckland. His name is recorded, of course, in the leading American and foreign biographical dictionaries of artists. And his canvases embellish the walls of many museums and private homes. But there has never been an opportunity for a conspectus of his entire oeuvre. He had his patrons in his lifetime. The need now is for some post-humous Maecenas.

Meanwhile, it so happens that the Town of Heath's Bicentennial Year is also Robert Strong Woodward's Centennial Year. And it is therefore all the more fitting that the citizens of Heath should, through this Bicentennial Book, remember and salute someone who fell in love with Heath and who proclaimed that love in such a special and effective fashion.

Alastair Maitland

1985