Harry Elmore Hurd Critique

A critique article by Harry Elmore Hurd, published in the Boston Breeze, June 5, 1931.

Mr. Hurd died in 1958 and the Boston Breeze is no longer published and has apparently gone out of business.

It may appear to be a far cry from the field of literature to the magical realm of landscape painting, but the accomplishments of Robert Strong Woodward forcefully illustrate one of my convictions concerning creative writing.

Robert Strong Woodward sees the glory of his own countryside. Born in Northampton on May 11, 1885, he, like Henry David Thoreau in his day, finds inspiration enough in his beloved home-country. The world not only beats a path to the door of the man who can "make a better mouse trap," but its choicer souls at least, the spiritual children of John Ruskin, seek out Robert Strong Woodward in his studio at Buckland, about two miles from Shelburne Falls. Rockwell Kent and Chauncey Ryder made their way to the door of this man who "paints with the brush of a poet," as do hundreds of less creative persons who worship Beauty.

When shall we learn that we do not have to go somewhere to find Beauty: We only have to be something. Mr. Woodward's native soil is to him what the woods of Barbizon and Fontainebleau were to Rousseau and Corot. A friend of his has said of him:

"Every stone in every crumbled wall, every tree in every pasture, every frog in every brook, every wide weathered pine plank in every faded red barn" claims the artist's affection and inspires his brush. "He is the poet in paint of his own locale, as Housman wrote of Shropshire and Hardy of Wessex."

We do not find the genesis of his art either in heredity or in the formal training of the art schools. On his mother's side, the Strong family tree gave flower to Caleb Strong, who was governor of Massachusetts in 1806; and to Sidney Strong, the legislator-grandfather of the artist, but neither the Strongs nor the Woodwards produced painters.

Although Robert Strong Woodward spent one hectic year at the Boston Museum School, when he was about twenty years of age, poor health prevented him from attending classes regularly. He was trained to be a civil engineer, rather than an artist, but while quite young, his interest was diverted, and he became a commercial artist, beginning his artistic career as a creator of fine lettering and illuminated manuscripts. Although he has abandoned the earlier field of illumination, it is a high tribute to his genius that such connoisseurs of illuminated manuscripts as the Grews, the J. P. Morgans, the Elliots, the Lowells and the Marshall Fields have included his work in their priceless collections.

During the (first) twelve years of his oil painting, Mr. Woodward has won a foremost place among American landscape artists. When he had only been painting a year, he was awarded the First Hallgarten Prize at the National Academy of Design, New York. Incidentally, this was the second picture that he had offered to a public exhibition. In 1920 he was given Honorable Mention at the Concord Art Association; in 1927 the Springfield Art League awarded him the First Landscape prize; and in 1930 he was awarded the Gold Medal of Honor at the Tercentenary Exhibition, held in Horticultural Hall, in July. The Springfield Art Museum owns three of his canvases: the Forbes Library of Northampton and the Public Library of Stockbridge, each owns one of his paintings. Among the many society people who possess paintings by Mr. Woodward are Mr. And Mrs. Amory Eliot, Mr. and Mrs. Francis M. Whitehouse, Mr. And Mrs. Walter D. Denegre, Mr. and Mrs. Lester Leland, of Manchester; Mrs. William H. Moore, of Pride's Crossing ; Mrs. George Lee, Mrs. Nathaniel Simpkins, of Beverly Farms; Dr. and Mrs. L. K. Lunt, of Concord; Mrs. Dana Malone, of Brookline; the late Mrs. Henry S. Shaw, of Milton; and Mrs. Henry P. King, Mr. John T. Spaulding, Mr. Franklin H. Beebe, Dr. and Mrs. B. T. Guild and Mrs. Eugenia B. Frothingham, all of Boston.

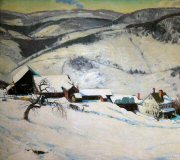

Robert Strong Woodward is a sort of self-appointed committee of one to make certain that no season shall arrive in New England without proper recognition. Like George Innes, and the landscape painters at Fontainebleau and Barbizon, this artist abandons the grandiloquent and magnifies the familiar. Possibly his first love is for winter, although he does not go out-of-doors, like Gardner Symons, when the thermometer registers zero, you will find him painting when it is so cold that he is forced to build a bonfire. Sometimes Mr. Woodward sets up his easel in a friendly farmhouse and captures his subject through the window. An understanding critic has written:

"He loves winter scenes because he can get the structures of trees. There is something that eternally intrigues in those gaunt arms against a clear hard sky, as Dore knew and Durer. Snow and remote mountains, brooks cutting a wayward path through shattered ice "there is the influence of Gardner Symons, but surely legitimate, for what would New England be without its winter?" Like the poet, John Greenleaf Whittier, this sun-bronzed artist loves Winter when she comes down the year, clad in dazzling white. Many Bostonians admired his New England Drama when it was shown at the Boston Tercentenary Fine Arts Exhibition. It shows a substantial country home, with its rambling sheds and barns zigzagging across the foreground beyond a winter-stripped apple tree. There is no feeling of desolation, or even of isolation, as the friendly hills lift their snow-covered and tree-patterned shoulders beyond and around the farm buildings, as though they were protecting the occupants from the less peaceful world. This canvas is a Snow-Bound in oil: it is as characteristically New England as Whittier's classic poem. There is uplift and strength in this painting. Possibly it is the artist's training as an engineer which enables him to capture the massiveness and ruggedness of the uplifted earth, but it is a pleasing forcefulness revealed in the glacial-smoothed bones of the earth; rhythmic structures that contrast with the angularity of the rambling farmhouse. One seeing New England Drama feels that he would like to return to the chore-life of the country, to split wood in the backyard, and to feel the frost bite his face.

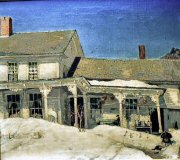

When Drifts Melt Fast won first prize at the 1927 Exhibition of the Springfield Art League. Many Bostonians have become acquainted with Mr. Woodward's charming winter scenes at the Myles Standish Galleries located at Bay State road and Beacon streets; indeed Mr. William Christopher Mellsop has opened his galleries to the work of this artist twice in three years. Winter Silence is characteristic: it shows a frozen pool in the heart of a dense woods. The darkness of the forest is contrasted with the feathery plumes of the snow-covered branches. Dignity of Winter is full of power and silence. Standing in the deep snow of the foreground, we look across a tree-shadowed valley to a snow-patched mountain in the middle distance. A Country Piazza selected from the Corcoran Museum Show, in March, for reproduction in The Arts Magazine, is a genre picture of a house-corner and a lean-to shed.

One member of the household is drowsing upon a settee. The milk pails are overturned upon their pegs, and three turkeys have ventured forth upon the melting snow. Even as Robert Burns lifted the genre songs of Scotland into the realm of poetry, so Mr. Woodward has given significance to a subject as plebeian as a snow-isolated farmhouse but as significant as the lives of those hardy wrestlers with the seasons who give sustenance to the world.

In springtime, Mr. Woodward takes us into the sugar groves. A canvas like Steaming Sugar House carries the country-born back to the promising days when Spring approaches White Winter, hesitatingly but warmly. Sugaring-off is always a delightful experience. It is the hour when the wind-twisted trees feel the pulse of life. One who has not poured hot syrup upon clean snow cannot fully appreciate the truthfulness of canvases like Steaming Sugar House and When Sap Runs. These are perfect compositions. The crooked arms of the maples arabesque the sky. The bare bones of the maples induce in the beholder a sense of the struggle and age of these sugar groves. After all, the silhouettes of stripped trees against bluely-shadowed snow are as beautiful as the green days of mid-summer! I am not forgetting that sentiment easily spills over into sentimentality, but I am guessing that many persons who watch Mr. Woodward's sap-gatherers toiling towards the sugar-house, carrying red pails of sap, find themselves yearning for the glad days of youth "down on the farm." Spirals of blue steam and patterned clouds gladden the skies of these paintings.

When Nature, ashamed of her nakedness, dons her half-finished garb of green and Spring bows to the coming Summer, Mr. Woodward becomes as primitive as Rousseau. He is fond of camping, often sleeping under the stars in open pastures, or crawling under a pup-tent in bad weather. The work of this sun-bronzed artist, like that of William Littlefield, "has a decidedly energetic outlook on life and nature, the same masculine quality, the same feeling for the anatomy of the earth."

Although we would like to travel the Buckland-Charlemont road with the artist, visiting old farms, sketching quaint bridges and capturing the strength of the hills, we shall mention only two "loves" of the artist."

Someday the artist hopes to have a show of nothing but barns, but, alas, barn subjects are so popular that Mr. Woodward is unable to accumulate enough of these subjects for a show. He is sometimes driven to conceal a barn picture in the hope that the potential purchaser will "take something just as good." Every art-lover knows Monet's "classic haystack." Mr. Woodward is immortalizing our New England barns.

Up the River Road is typical of his farm-house group. A leisurely road winds under the shadow of lofty mountains and between the house and barns of typical New England farm buildings. Aside from his artistic contributions to our New England history by preserving an oil-record of the homes of the pioneers.

Tree-plumed pastures, majestic hills, luxuriantly leaved maples, bowing slightly to the breeze, fantastic clouds against colorful skies, win the heart of this genius. He will never make the mistake of the man who left his New Hampshire hilltop "with its view of Kearsarge, Monadnock and other mountains, to seek his fortune in a Mid Western city, but who came back shortly with the one laconic plaint "he could not see far off."

The cycle of the seasons is complete in autumn. Like all true Nature-lovers, Mr. Woodward captures the gladness of those crisp days when the birches throw off their golden capes and curtsy to the pines, saying, "Good-bye, Old Shaggy Locks, we are going on a long, long adventure."

What shall we say of this man's artistic ideals? I suspect that he would say with George Innes: "The true purpose of the painter is simply to reproduce in other minds the impression which a scene has made upon him. A work of art is not to instruct, not to edify, but to awaken an emotion. Its real greatness consists in the quality and force of this emotion." Mr. Woodward paints quickly and broadly. He would rather scrape a canvas clean, after he has worked on it two weeks, and paint it all over again in one day than have it look as if it had been worked on two weeks. He chooses a middle course in his technique, avoiding both the too impressionistic and the too detailed. Mr. Woodward says: "I have no patience with the so-called ultra-moderns, who defy established technical law and expression and careful craftsmanship and drawing, yet I have no sympathy with the over-studied, polished meticulous academic painting of exact replica. The 'likeness' of a landscape, even if exact, is dead in paint, unless it holds as a picture the spirit and essence and expression of that landscape. I try to paint the feeling of a landscape, the 'emotion' of it, as well as the facts "this seeming to me a more impressive, lasting and interesting thing than merely the exactly recorded fact alone."

The fact that Mr. Woodward has exhibited in the following shows, argues for the success of his paintings: The National Academy of Design, New York; the Pennsylvania Academy, in Philadelphia; the Carnegie Institute, in Pittsburg; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Albright Gallery, in Buffalo; the Corcoran Gallery, in Washington; the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Boston Art Club; the Salmagundi Club of New York; the Myles Standish Gallery, of Boston; and scores of smaller galleries. He is a member of the Boston Art Club, the Salmagundi Club and the New York Water Color Society.

One feels that it is good for art to be occasionally challenged by men who blaze artistic trails, alone. After all, there were artists before there were schools of art!

White Clouds is now being exhibited in one of the windows of the Myles Standish Galleries. A shoulder of the Berkshires is seen over a disordered stone wall and an old road. The mountains are framed in the full bloom of old apple trees. Above the trees and the majestic mountains, flocks of cumuli repeat the pattern of the trees against a chromatic sky. There is no fussiness or over-detail: the man who painted this canvas is glad to be alive!

As I turned away from White Clouds I halted, filled with divine amazement, for directly ahead of me, in the heart of busy Boston, three scraggly apple trees were flinging forth their bloom. It is one thing to come upon a blossomed tree in the open country, but it is like a direct revelation from Heaven to discover full-blown apple trees in the heart of noisy Boston! Beauty is always breaking through the veil, but only those who love Beauty stop to give thanks for these poetic experiences. As I swung down onto the Esplanade, full of thoughts of the creator of White Clouds, I pondered the appropriateness of the revelation which I had witnessed. It was as though the blossoming apple trees, in the heart of the city, had adorned themselves in pink and white that they might honor him who paints Nature with the devotion of a High Priest.