Colton's Radiogram Broadcast - 1934

Website editor's note:

Clifton Richmond, the author of the following article about Robert Strong Woodward, was an industrialist living in

Easthampton, Massachusetts. He purchased the Elastic Web Company in that town from the original owner, George S. Colton, and took over the management for many years.

He was a frequent visitor to RSW and purchased a number of oil paintings from him. He had a summer home in Goshen, MA and was visited there by RSW both to deliver

finished paintings and at other times simply to visit with him. Mr. Richmond wrote the following critique of RSW's work and tells of his relationship with him. The article was

published in a small magazine distributed to all the workers in his factory and was read over the radio on a program sponsored by the Elastic Web Company. The old factory

building of the company is now a historic site in the village of Easthampton. At the death of Mr. Richmond many of his paintings were sold at auction and many others were

willed to local institutions such as the Williston Library in Easthampton.

A RADIO BROADCAST IN 1934 BY THE COLTON ELASTIC WEB CO., EASTHAMPTON, MAwritten by Clifford A. Richmond

"Courage multiplies the chances of success." ---Coleridge

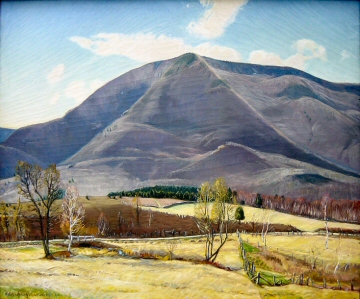

Many years since, Robert Strong Woodward took out artistic letters patent on the scenery of Western New England.

The law, of course, provides that one who pays taxes has definite property rights but legislation does not exclude the quick-appraising eye of the artist from evaluating scenes of God's green

footstool on his own terms. The artist recognizes his own, no matter who hold the title.

Without robbing the taxpayer, he transfers to canvas that which belongs to him and goes

his way, recognizing the while that the cost of seeing and appreciating and the power to transcribe are the add-up of a lifetime - perhaps, many incarnations. Quien sabe?

Outdoor

western New England is Woodward's very own, be it Mount Equinox in April,

The Mountain Shoulder in midsummer, An

October Flame, or a winter scene, so vivid in the warmth of its impress of cold, so majestic in the lights and shadows of the sun on the drifted snow that you feel the invigorating tang of frosty air.

Woodward delights in painting scenes of a rural New England that is fast passing from view, scenes which start a fine matching of memory against the vision of the artist, scenes that accelerate heartbeats.

My own feeling is that the paintings of Woodward are less a transcription of the views his eyes have seen, than that a wonderful view is an excuse for Woodward to unloose what is in his mind and heart.

Woodward thinks broadly and the urge within him demands that the canvas on which he paints shall be sizable, the view expansive.

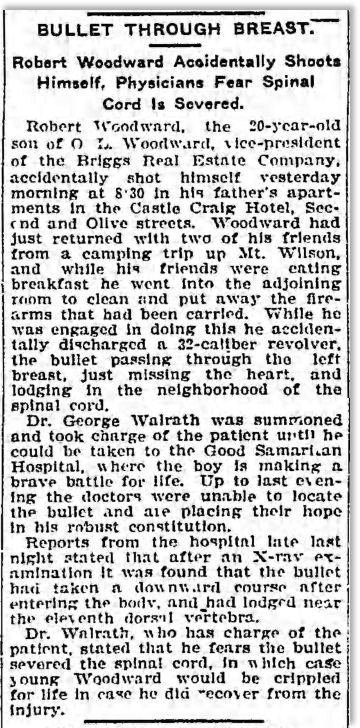

Sept 4, 1906 LA Times Clipping

Sept 4, 1906 LA Times Clipping

Those "ministering angels that tend on mortals' thoughts" keep flashing before me the word courageous. It is a word that fits and tells volumes

about Woodward. At the age of twenty a revolver accident caused him years of hospital experience, absolute paralyzation of the lower limbs, and the lifetime necessity for a small retinue of nurses

and attendants. Estimate that expense, especially to one obliged to make his own way, and thank God that that way could be through expression of the great desire of his heart to be an artist.

In 1922 Woodward's studio, including all his production and working equipment, burned to the ground. Again early in 1934, while Woodward relaxed a bit to witness a movie, one scene of which showed

a house struck by lightning, his own home and studio on the outskirts of Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, were struck by a bolt from the sky and utterly destroyed. The paintings - God be praised! ---- were saved.

Put yourself in this man's place. Imagine, if you will, the torrent of conflicting emotions at finding everything but his paintings gone - all his sketches, his books, his letters, utensils, household goods, every device

and convenience his ingenuity had studied out to facilitate the mode of life and work which fate had meted out as his portion. At such a time the easiest thing to homebrew and the last thing to requisitionfrom

Sears, Roebuck & Company - if the catalogue escaped the fire - would be a case of jitters. To meet such a catastrophe and treat it as a hard scrimmage in the game of life, a downing behind one's own lines

with additional yards to gain to retain the ball, tests one's poise and proves Mr. Coleridge

knew the facts. "Courage multiplies the chances of success."

Insurance adjusters seek to settle for items destroyed on the basis of their depreciated value. In the estimation of an adjuster a palette

that may have cost five dollars has depreciated while to the artist it carries that confidence of right colors, that "intimate feel" which five dollars or five time five cannot replace. Insurance that gives the artist new

brushes for old falls a long way short of restoring to him that something he has worked into them by which the brushes become handmaids to his soul. Ashes - all the build-up of years, the infinite, uninsurable

arrangement, detail, expression - ashes of roses along with ashes of wood.

From a valued letter I quote: "All ahead is a blank wall to me. What slight insurance I had was cancelled by mortgage, which

leaves me at forty-nine with many to support and salary, and an intricate, expensive business to run - leaves me at forty-nine at zero financially." Courageous? I'll tell the world that courageous is the word.

Early in September, when goldenrod, the purple closed gentian and wild aster paid floral tribute to the day, we had a joyous feast with Woodward at a spot in the fields back of his former home, where was built an

outdoor oven, hard by a cascading stream that zigzags down to an old weather-worn building, at a bend in the road where the macadam leads toward the Mohawk Trail.

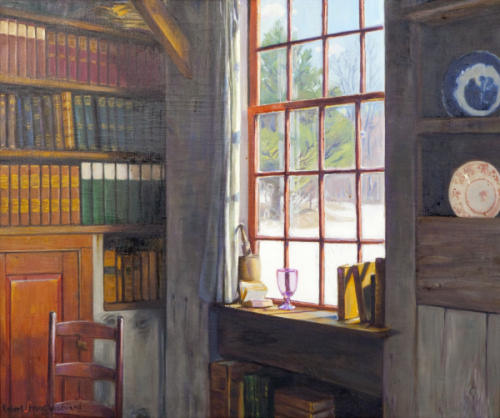

A picture of the Little Shop

A picture of the Little Shop

This little grey shop standing at the edge of an embankment was once upon a time a small cutlery mill, then a cider mill,

then for thirty years the dwelling of a recluse. Once there was a water wheel to tussle with the stream beforeit escapes under a stone bridge. At the other end of the building is a large clump of lilac

bushes and far up the meadow through which the stream runs there is a beautiful background of woodland.

This little grey shop by the side of the road is the only remaining bit of

studio-background left to express the artist's intense feeling for rural New England.

When Woodward unwillingly took it over, and the acreage with it, for three hundred dollars, the

unwillingness was wholly financial. Reconditioning was no easy task. To that end the artist scoured surrounding hills and, board by board, nail by nail, brought back a wealth of very wide,

weather-beaten boards and hand-wrought nails. Each deserted farm or old cellar hole yielded something. With these boards the interior of the building was re-lined; yet there is no evidence by a cut

edge of newness, the boards having upon their edges the loving weather-worn grey of time. Courageous? Yes - and patient. A wealth of fine feeling, know-how and patience, fused together, have here

reproduced the look of age that has a charm all its own.

The Book Corner; the only known

The Book Corner; the only known

painting from inside the Little Shop

The natural color of the woodwork, the pewter, the grey and black curtains and the soapstone stove, are relieved by the dull

red of the window sashes, the doors, an old chest, a dish of rosy apples, pieces of antique glass on the window sills. Nor does the eye miss the harmony of the old grey-green chairs, table, and the old crock

on the floor filled with laurel leaves. The antique furniture and decorations caught the eye of the Lady-who-chums-with-me, also the contents of the set-in wall cupboards, the ancient latches and "Holy Lord"

hinges.

The many windows in this building all have small panes of glass. Not one of these is new, nor is there an old pane cut down. Toward completion of restoration, the artist was asked if a

few lights of old glass could be reduced in size. He replied: "No. We must be patient and eventually find them." The artistic desire for accurate reproduction versus the business urge to have done with it.

If you like this place, then keep mum; Woodward will talk interestingly. But, if your glance about prompts some such observation as "It is a cute place," Woodward will do the shutting up and so you will

miss the fine, easy flow of one who devoutly loves and translates himself into his work. I thank you for the word courageous - it fits the man.

One morning in 1918, the thought came to Woodward - as thoughts so often do to alert minds while shaving - that graying locks

and fleeting time demanded he make an end to seeking a living through decorating cards; that he must at once set forth to accomplish his long-cherished dream of being a landscape painter. Long years

Woodward had been thinking toward this purpose and, when the hour arrived, he quickly marshaled himself into action though for a space it meant "living on faith and dandelion greens."

Woodward then did the thing that an accepted artist cordially dislikes to have put up to him. He took his paintings to Gardner Symons, at Colrain, near by, and asked for criticism. Symons' kindly indulgence

promptly quickened to genuine interest. He advised exhibiting at the National Academy. This Woodward did and, glory be! promptly won recognition. New England men and women dwelling far from their

native hearts will find in Woodward's paintings the answer to their homesickness---"the pictures I want."

Of course, Woodward did not lasso success without an infinite number of failures. The

full-limbed artist walks miles in painting a picture and enjoys the privilege of standing back to study effects. Doing all his outdoor work from the back seat of an automobile, Woodward had to learn to unfocus

his eyes so that he could be close to a lilac bush by a doorway and accurately translate how it must appear at a distance, or the exact effect of sunlight through the leaves playing upon an old house, rich in its

buttermilk red - infinite touches that reveal a picture as art.

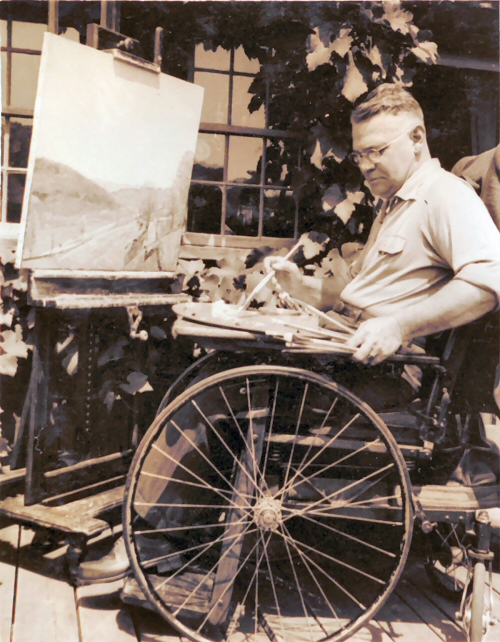

A picture of RSW painting from his 1936

A picture of RSW painting from his 1936

Parckard demonstrating the difficulty RSW would

have stepping back to gain a broader perspective

In Chicago for the Century of Progress in 1933 the first thing we did was to go to the Art museum, where many of the world's finest

paintings were loaned for the occasion. I do not like to go catalogue in hand, do not want to be told, "Here is a Rubens, there a Rembrandt, yonder a Van Dyck." My preference is to find pictures that I like and

tilted ell and piazza with post wee-waw under a sagging, snow-covered roof.

The picture shows just such a scene as travelers through New England recall. Flowers show at the curtained lower windows;

frost alone decorates the windows upstairs. A turkey gobbler, standing where high-piled snow makes a miniature canyon, views the golden ears of seed corn hanging above the upturned milk pails on a bench and

suggests, "When do we eat?" A muffled old man dozes on a green settee. Nothing is missing, not even the fine shadows that clapboards make.

Impressive is the warmth of the sunlight, the chill of the shadows, the sense of remoteness, the tranquility, the humdrumness of country life

- the picture seems to quietly say to you, "This is New England in midwinter; stop by when you have news."

To the Lady-who-chums-with-me I remarked, "That canvas in its style and coloring suggests

Woodward." And it was Woodward's Country Piazza, loaned by the Canajoharie, (N. Y.) Art Museum. So, when I eat good bacon, I am

doubly glad that some of the bacon Beechnut Bacon brought home was invested in Woodward art.

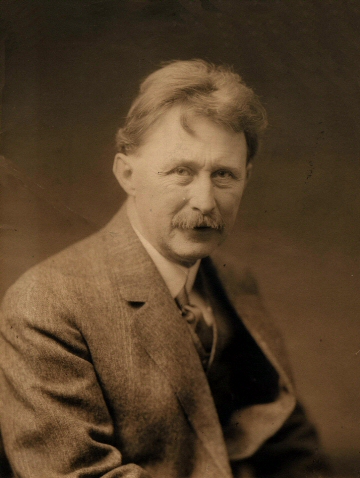

Woodward in his wheelchair just outside the

Woodward in his wheelchair just outside the

front doors to the Southwick Studio

A very certain charm and distinction about his work make it a joy to possess a Woodward, either a pastel or an oil. If history

holds true to precedence, that fact will be more keenly recognized when the artist has marched on. But - you too, may then be permanently away and perhaps an appreciative executor, looking over your

assets will remark "I wish he had gone less into stocks and more into Woodwards."

Recognizing that his physical handicap is not a legitimate public concern, Woodward has steadfastly refused

to permit mention thereof in print. Art itself, not human interest in the artist, must be the measure of meeting the world and coming a winner in a fair fight. But, in spite of obstacles that might well have

overwhelmed him, Woodward has won a place in the art world and though I listen to his protests I cannot tell this human-interest story and leave out vital facts, nor the word "courageous."

Perhaps the fettering of genius is the needed ignition to start the engine and keep it going. Unfettering of one who has been fettered usually destroys the output. Order a book to be produced, answering a writer's fervent prayer for recognition, and it is ten to one he will straightway lack the compelling urge to produce it. Had Woodward's uncomfortable cot been a bed of roses, he might have produced winter scenes that would be cold and leave the onlooker likewise. I dunno! I hazard a guess that the quality of his work, the temperament and technique that enter in, by which on a single canvas he produces the natural variations of cold snow on which blazing sunlight almost blinds the eyes, or on another canvas the colorful r esplendent glory of an October Flame, are a summation of Woodward's courageous ability to turn the clouds inside out and show the sixteen- to-one lining. My guess is that all great art is at great price; that there is a divinity which shapes the artist's course, rough adventures and all.