Winter Evening Stream Paintings

A scene captured from the painting, Tranquility (1945), best illustrates the subject

Essay written by: Dr. Mark Purinton (2011)

Updated and edited by: Brian C. Miller (2024)

Woodward's Redgate Studio in what is

Woodward's Redgate Studio in what is

probably summer but it illustrates the proxim-

ity of the woods where the stream is located.

Part 1: THE ZENITH OF POTENTIAL

Early in his career after recovering from his gunshot accident, Robert Strong Woodward began living and working in a studio he called Redgate. The building was the old "milk house" on the farm of his Uncle Bert and Aunt Tella Wells (his father's sister). He was having difficulty supporting both himself and his necessary hired help by just producing bookplates and small illuminations. He began to take up oil painting and produced a number of large oil paintings of the view out his studio windows. One of these views was of a winter scene of a pool of water fed by a small brook surrounded by trees.

We have found it impossible to accurately catalog the paintings made of this scene. His first

paintings were done directly in the Redgate Studio, looking out the window. When Redgate Studio burned down, he

continued to paint this same scene while working out of the Hiram Woodward studio. It is not known if he went back

to the original location after Redgate burned down, or whether he simply copied an original painting from Redgate.

Later still, he produced more copies at the Southwick Studio, sometimes destroying the original. It is unknown

whether any of the painting names for which we have no pictures are ones that he personally destroyed.

This essay will attempt to describe these painting, what Dr. Mark called Winter Evening Streams (abbr. Winter Evening Stream), in

chronological order as best we can. To our knowledge, one of the earliest, perhaps the first, painting of this

scene was named Winter Mist seen below.

Winter Mist, c. 1920 is thought to be the

Winter Mist, c. 1920 is thought to be the

first winter woods interior featuring water.

From Woodward's Painting Diary:

"Winter Mists: Painted

circa 1920 or 21. An upright woodland winter interior on a gray day with mist weaving through the woods painted

from the window of my first little studio 'Redgate' (the first one to burn) just following the time when I had

received the First Hallgarten Prize at the N. A. D. in 1919 when I painted many woodland interiors of similar

type. Bought in the early 1920's by Mr. and Mrs. Wm. D. Vanderbilt of 527 West 121st Street, N. Y. C. according

to them for their 3 young sons 'to grow up with.' Later they purchased a chalk drawing for each one of the sons

as a wedding present when each one was married, a nice idea indeed!"

ADDENDUMS to this FIRST SECTION: by BRIAN, JANUARY 2025

_______________________________________________________________

It is known that RSW did not start to write his painting diary until approximately 1940. He attempted to fill in earlier paintings by memory. We have found more than a few examples of mistakes and omissions throughout the decades he tried to recall. One specific example is the mix up between the paintings, Winter Silence and Winter Poolthat is the result of the artist making numerous versions and sizes of similar scenes.

The mystery for us is why Woodward did not just refer to his newspaper clipping scrapbook to refresh his memory. Below is a diary entry attributed to Winter Pool and later proved to be Winter Silence.

734.png?url=photos/WinterEveningStream/winter_silence_rotogravueLG.png)

Winter Silence, Sepia Print Image - - If you enlarge

Winter Silence, Sepia Print Image - - If you enlarge

the image, you will see the original Rotogravure page.

From Woodward's Painting Diary:

"Winter Pool : Painted

prior to 1930. A large early canvas of a theme I painted several times with slight variations and different

compositions, tho the only one I made of it in this larger size, 36 x 42. A black turbulent pool of a stream

flowing thru dark winter evening woods, curving about a large clump of flesh colored winter beeches in leaf

on the snow-drifted bank. (Mr. and Mrs. Robert T Lee of Manchester, Vt., Mrs. Roger Smith of Gardner, etc,

own other canvases of the similar theme). Largely exhibited about the country, given a very large rotogravure

illustration by the Sunday Boston Herald (see my clipping book) and finally bought by Mrs. Wm. H. Moore to give

to her sister, Mrs. Smith of Chicago. Mrs. Smith died around 1940 and the picture was taken and is now owned

by her daughter, Mrs. Sellar Bullard of 'Far Horizons [Ranch]' Stow Canyon Rd, Goleta, California."

We do not fault Woodward for believing he was accurately recalling the name of this painting. We all believe the recall of our work and experience is correct, but we are talking about hundreds, if not a thousand, works of art from 1917 to 1940, and even the diary entry itself says to "check my clipping book." Despite the inaccuracies, we can piece together some sort of timeline, after all, the only substantial differences between Winter Pool and Winter Silence are the sizes. Both were painted around the same time.

672.png?url=../Gallery/photos/out_of_the_mist(25)672.png)

Out of the Mist, 1919

Out of the Mist, 1919

The earliest known deep interior wood painting.

Note how similar the twin beech trees on this

canvas are to the ones found in Winter Mist.

When Dr. Mark began the website in 2002, he first started with building the artwork pages. He used two sources; the first was the 1970 catalog of Woodward's work prepared by the Deerfield Academy's American Studies Group, a group of students who devoted their entire school year to assembling as comprehensive a list of the artist's work as possible. Dr. Mark assisted the group along with Woodward's friend F. Earl Williams, and cousin Florence Haeberle. The group estimated that Woodward's catalog comprised of as many as "300" paintings.

Today, the catalog is approaching 800 paintings as we discover more each year. The second source Dr. Mark used was the original sepia print negatives that remained in the estate. He developed many of them to later scan into a digital image and add them to the artwork page. Along with the numerous paintings from the artist's private collection of his own work and the many people "Doc" knew to own Woodward paintings, he set out photographing as many as he could.

A photograph of the brook behind Woodward's Redgate Studio

A photograph of the brook behind Woodward's Redgate Studio

a decade or more after the studio burned. We believe that what

produced the large pools of water was the snow damming the path.

The problem with this is that we have no idea what Woodward did early in his career to photograph his work to send to galleries (This is how most exhibitions worked- you sent them a picture of the painting and on the back a colorful description to give the show's jury an idea of its tone and hue, etc.). Complicating matters are the two fires that destroyed his first and second studios, losing many of these early records along with it. The inconsistency of the diary entries for the years before 1925 makes this task even more difficult. Still, the internet has grown exponentially since 2010, and we have been aided greatly by these advancements, in particular, searching newspaper archives for any mention of Woodward, and focusing on the time period in question.

Dr. Mark also had the idea that he would start making what he called "Scrapbook pages," assembling and writing essays on certain topics and telling stories of his own about his time working for the artist. Mind you, he started all of this in his eighties, AFTER his retirement. We carry on this tradition, which originated with Dr. Mark, and have done our best to preserve his original work and build on it as we discover new information. One such Scrapbook page, as such, is an essay written by Brian about the evolution of the Window Picture Paintings, and he made an interesting connection between what we today call, "Quintessential Redgate Paintings" and his Window Picture Paintings. The last section of the essay is devoted entirely to the Redgate paintings. See the link below...

OUR ESSAY ON THE EVOLUTION OF THE WINDOW PICTURE PAINTING

( Page will open in a new tab)

The Tranquil Hour, c. 1924, this painting and its similarly

The Tranquil Hour, c. 1924, this painting and its similarly

named painting below were most likely made after the Redgate fire.

The style matches similarly dated paintings of the same time.

Below we added some addition images not available when Dr. Mark first created the original page

of this essay. As you can see, these paintings pictures have come to us over the years from their owners, and

two have names on their stretchers suggesting they exhibited somewhere, however, not only do we not have diary

remarks on the paintings by the artist, we also do not have the year's they were made. Still, we have enough

evidence from other paintings with known years to at least estimate the order in which they were made.

Over the years, we learned that Woodward erred in buying pre-treated primed canvas stretchers in bulk from an

art dealer in Boston. The problem was that the manufacturer of the pre-treated canvases used animal by-products

in its primer (its technical name is "Gesso") and the animal by-product shrunk, hardened, became brittle, and

cause the paintings to crack quite severely. Many of these paintings were dated between 1920 and 1922, when

demand for his work increased with his success. Perhaps he thought he was saving time...

Unnamed: Wooded Stream (pre-1920)

Unnamed: Wooded Stream (pre-1920)

This painting is most impressionistic of the

three. It is also interesting that it depicts the

brook in its natural state, before flooding.

It could be as early as 1918, the first year!

Midwinter (between 1920 - '22)

Midwinter (between 1920 - '22)

The web-like craquelure on this piece gives away

its age. Also, its brightness which may be a re-

sponse to the wooded interior paintings being

too dark and murky. Did you notice the brook?

Tranquil Hour (post Redgate fire)

Tranquil Hour (post Redgate fire)

The reflection in the photo reveals the brush

strokes on the canvas suggesting to us its age.

RSW began his career using heavy pigment on

his work but changed after the Regate fire.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

END OF FIRST ADDENDUM

Woodland Mystery, sepia, c. 1951

Woodland Mystery, sepia, c. 1951

If you look closely, you can see the "Mist"

under Mystery from the back of the sepia print

Part 2: RETURNS WITH AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Apparently this scene was one of his favorites. It was not only one of his earliest paintings, it was also one of his last. He made versions of the scene in at least three of his four studios. Some two decades after Redgate studio burned, I can remember RSW asking me to pull out one of the original paintings from the back storage room. This was during cold winter days of World War II, when he could not paint outside. He would place it under the natural light from the North window of his Southwick Studio, and then make a duplicate canvas. I am aware of at least two oil paintings made in this manner.

Woodland Mystery appears to be the final painting of the series. RSW hand wrote the title at the bottom of the sepia print. Apparently, even he, was confused about the title. As shown in the close-up below, it appears that he originally wrote "Woodland Mist," then corrected it to read "Woodland Mystery." At this time, we do not know if there is another painting named "Woodland Mist," but there are no diary entries, photographs, or mentions of it in any newspaper articles or exhibition notices. Below are three diary entries, also from after the Regate fire.

North Adams Transcript,

North Adams Transcript,

Dec. 20, 1922

The article incorrectly said the paint-

ings where going to a "museum."

They were headed to the Macbeth

Galleries in New York City.

Woodward's Diary Entry for, Evening Stream 2:

"Painted prior to 1930. One of my

early paintings of a subject matter I often used from my first studio Redgate which burned. A large one 36 x 40 of

the same subject, or similar subject (but reversed) which I called Winter Pool. Mr. and Mrs. Robert T Lee of

Manchester, Vt. own a larger panel of the same subject matter."

Woodward's Diary Entry for, Evening Glow:

"Painted in 1923. This painting of an evening stream in sunset glow I made soon after Redgate burned and sold to Mr. and Mrs. Walter D. Deneque of Washington, D. C. and Manchester, Mass. ( Mr. Deneque is now dead.)"

Woodward's Diary Entry for, Evening Stream 3:

"Painted in 1923. This painting, (size uncertain) like the above I made soon after Redgate burned and sold to Mrs. Charles E. Ulrick, 1808 Columbia Terrace, Peoria, Illinois. Now probably in possession of her daughter Lena Ulrick Belsley (Mrs. Ray Belsley) of Peoria, Il."

Editor's Note: The popularity of all of the interior woods specific to the Redgate studio launched the artist's career. He won the Hallgarten First Prize of 1919 at the Nation Academy of Design's annual show for Between Setting Sun and Rising Moon , and the New York Times Magazine review of his work compared him to artist Robert Blakelock, the most popular American artist of the 19th century and a tonalist. We believe Woodward was also inspired by James McNeill Whistler, who named his moody and tonal paintings using musical terms like symphonies and even nocturnes (a musical composition, often for piano, that is inspired by or evokes the atmosphere of the night, typically characterized by a romantic and dreamy, sometimes melancholic, quality). Of his first four paintings bought by museums, three were tonalistic 1926, Lyman-Longfellow Residence exhibition in Boston, the market for them had cooled quite a bit.

SEE ONE OF WHISTLER'S FIRST NOCTURNES: BLUE AND SILVER - CHELSEA

( Page will open in a new tab for the Tate Museum website)

ADDENDUM to this SECOND SECTION: by BRIAN, FEBRUARY 2025

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Evening Stream 1, c. 1919

Evening Stream 1, c. 1919

There are three verified paintings by this name!

The image above is the first and it is not a deep

wooded interior but rather the Deerfield River

in what we believe is the month of November.

When Dr. Mark wrote this essay in 2011, it was nine years into the website's existence, and he was 85 years old. Moreover, while the family had many of the documents Woodward left behind since 1959, the material was not only, not organized, it was scattered about in numerous storage areas and attics throughout the house. Doc did not begin to gather, sort and organize the material until after his retirement as a country doctor. He did a remarkable job given the task at hand, his age, and failing eyesight. Since then, with better methods in the cultivation and organization of the material, as well as new technologies to build databases and digitalize material... we simply have more context today. We can now cross-reference material and check information against multiple other sources.

William Macbeth: by artist Douglas Volk

William Macbeth: by artist Douglas Volk

The Brooklyn Museum of Art Collection

In all, we know of six paintings Wood-ward made from the same woods behind where Regate once stood after the fire. It is believed that Winter Silence, and Evening Tranquil Hour (pictured at the end of this section) were both painted in 1924 or '25. There are more Winter Evening Stream paintings but they never made it to be named or exhibited. Placed in storage because they fell just short of his high standard. They stayed there for the better part of twenty years until he pulled them out to "re-paint" them as new canvases in the 1940s. So the mid-1920s, as far as we can tell, are the last years he painted Winter Evening Stream paintings from the actual location.

For more context as to the disaster that derailed Woodward's career and reputation for four years and lingered another six years after that before he was fully back in the good graces of the art world, we must explain what caused the fire. The artist, under the pressure of his influential benefactors who pursued William Macbeth of Macbeth Galleries in New York City, the most prestigious American Art Gallery in the country, into giving Woodward his first one-man show. He had about 18 months to make 50 paintings, from which Macbeth was expected to select about half for the exhibition schedule in the slow month of January 1923.

Under the Winter Moon, c. 1922

Under the Winter Moon, c. 1922

The painting George Walter Vincent Smith purchased

for the Springfield Museum from the J.H. Miller Gal-

lery in March of 1922. Letters between himself and

Smith indicate Woodward's financial difficulties.

This was also during the 1920-'21 Depression, and money was very tight. We know he sold 6 of his much-loved early paintings wholesale to the J.H. Miller Gallery in Springfield for a thousand dollars. It is very likely that he did this to fund the supplies he would need to make that many canvases. In March of 1922, Woodward gives us a good idea of how much financial stress he is under by expressing to Springfield (MA) Museum Director George Walter Vincent Smith that he cannot accept the price being offered by the museum for Under the Winter Moon. While he is honored, Woodward tells Smith,

"...unfortunately my horse will not eat honor, nor my nurse

take it for salary, nor the hospital supply house for a wheelchair- (which I now need new) nor the local farmer for wood to

fill my gaunt shed!"

We learn his medical expenses per month run him around $4,800.00 in today's money. We also know from our records that he is exhibiting less, suggesting all his effort is being put into completing the Macbeth order.

George Walter Vincent Smith, benefactor of the

George Walter Vincent Smith, benefactor of the

Springfield Museum, and later its director, seen here

in his study. Smith began collecting art from around

the world as a businessman searching out the best

quality materials for his carriage building company.

It is interesting to us that Woodward would mention in his letter to Smith that honor won't fill his "gaunt shed" with wood. In hindsight, it seems as if the artist foreshadowed the event to come. The night before 50 paintings were to be shipped to New York City, the tiny Redgate studio (once a shed itself) was packed full of shipping crates. It was going to be a cold night, and he was concerned the paintings might freeze, so extra wood was placed into the stove. What was not accounted for was that the crowded studio, those extra logs, super-heated the already tight space, causing the chemicals all artist use in their craft to reach their flash point, igniting them into the flames that would destroy the entirety of the studio and all of its contents.

Mrs. Ada Small Moore from her Pride

Mrs. Ada Small Moore from her Pride

Crossing Estate, Rockmarge. The widow

of lawyer Wm. Henry Moore, the founder

of the Union Trust Bank and Nation Biscuit

Co. (Nabisco) among a number of others.

What is not known about the paintings is how many of them were Winter Evening Streams, or Wooded Interiors for that matter. All but one painting perished, and that painting, Snow on the Mountain, is not a wooded interior. This is such a critical point in the artist's career, and so many things will rise out of its ashes. First and foremost, this will be the last time Woodward would share some of the blame in his misfortune do to carelessness (the other two being the accident that left him paralyzed and when he moved across the country to go to art school in Boston without having a sustainable plan for his care and well being). He will make it on his own for the most part but after this event, Mrs. Ada Moore would level his playing field by covering the cost of his nurse and attendant for the remainder of his life plus some of the cars he used professionally to paint en plein air.

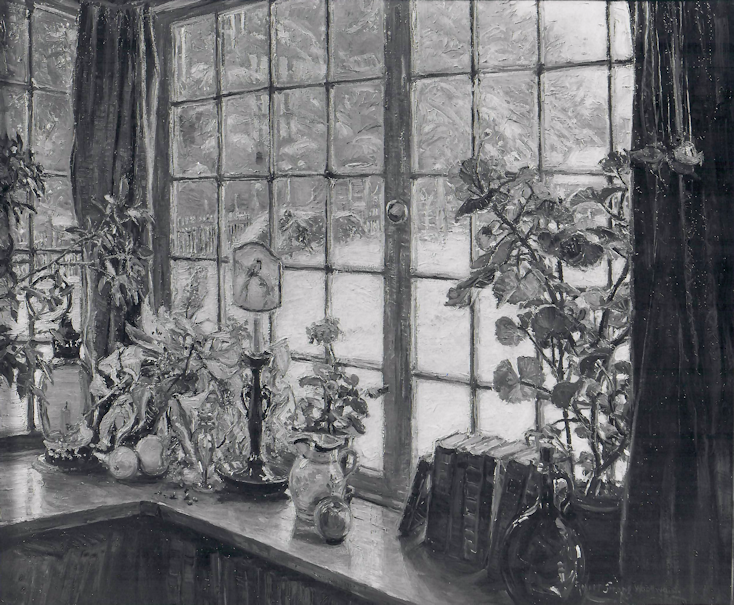

The Window: A Still Life and Winter Scene, 1924

The Window: A Still Life and Winter Scene, 1924

Purchased by art collector John Spalding from the 1926

Lyman-Longfellow Residence Exhibition and later to the

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as part of Spalding's gift.

He would also, at just short of 38 years old, own his first home. Woodward has been renting the main house at the Hiram Woodward Place since 1917, but now, in need of a new studio he works out a deal to purchase the 9 acre property that includes the cottage on the western edge of the property he rented between 1913 and '17. About a third of the large shed behind the house would be converted into his new studio and once it was ready to use one of the first things he did was paint his first Window Picture Painting, The Window: A Still Life and Winter Scene."

Evening Tranquil Hour, c. 1923

Evening Tranquil Hour, c. 1923

This painting hung at the annual 1924 Stockbridge (MA)

Art Exhibit. Despite having no painting diary entry and

given that his 1922 fire was nearly a total loss; this

painting either was made in 1923 or, hung in his home

as part of RSW's personal collection, thus was spared.

Three years after Woodward reportedly painted Evening Tranquil Hour (left), two Winter Evening Stream paintings appear at the artist's first One-Man Show in Boston on December 8, 1926, at the Lyman Residence. They are, Winter Silence (bottom left) and Evening Stream (bottom right). Both are the same pool of water from different sides. Only 11 paintings exhibited between the fire of 1922 and December of 1926. All but two were typical landscapes. Only Evening Tranquil Hour and Winter Silence were Winter Evening Stream paintings. As a matter of fact, Winter Silence, won top honors a month before appearing at the Lyman event when it hung at the Springfield Art League's special fall show. Evening Stream (#2) would hang in Stockbridge's annual art show in 1928 and finally later that year be part of Woodward's One-man show at the J.H. Miller Gallery. There will be an Evening Stream #3 made years later in 1932.

Evening Stream #2, c. 1924, 24" x 36"

Evening Stream #2, c. 1924, 24" x 36"

As stated there are three versions of this scene. Two are very similar in

their appearance and painted eight years apart. It appears that the third

painting was made for the Deerfield Inn and hung there for three years

before exhibiting four more times over a five year span up to 1944...

Finally, of last three Winter Evening Stream paintings mentioned in the previous paragraph, not one of them had any painting diary entry made by Woodward in the 1940s. Making matters worse, he would mix up Winter Silence with another painting we believe he made special for his patron-saint, Mrs. Ada Small Moore (one of the artist's powerful allies we suspect pushed Macbeth to give the artist his show set for 1923), confusing matters even further. That story is worthy of its own Painting Story Essay, but for now we will simply name the painting - Winter Pool, a 36" by 42" canvas, that has no exhibit record and we believe was not painted until 1927. As it happens, there was one correct fact about the painting. Woodward said it was the first purchased by Mrs. Moore... that is unless it was actually Road Guardians; a claim he makes for both paintings. Perhaps they were both first, and bought together but Winter Pool was made special because it was a gift for Mrs. Moore's sister. It was bought by Mrs. Moore but not for herself thus the conflicting painting diary entry comments. Both entries are true but not clear due to Woodward's odd approach to not being specific enough in detail for his painting diary.

OUR PAGE DEOVTED TO RSW PATRON SAINT, MRS. ADA SMALL MOORE

( Page will open in a new tab)

734.png?url=../Gallery/photos/winter_silence(24)734.png)

Winter Silence c. 1924, 30" x 36"

Winter Silence c. 1924, 30" x 36"

Pieced together from two separate clipping of the Dec., 1930, Boston Her-

ald special Rotograve section would become one of the artist's most refer-

enced paintings as, "typical of the characterful works of Mr. Woodward." Its

caption would be repeated 10 more times by newspapers over the next three

years which may be the reason RSW made Evening Stream #3 in 1932.

Winter Pool, c. 1928, 36" x 42"

Winter Pool, c. 1928, 36" x 42"

This painting is believed to have been made special for Mrs. Moore after

Winter Silence appeared at the 1926 Lyman Show, which we are sure Mrs.

Moore did not attend. She gave this painting to her sister as a gift.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

END OF SECOND ADDENDUM

From the window of the Southwick stu-

From the window of the Southwick stu-

dio balcony door (1940s). It is important to

know that the artist added at least six to sev-

en windows to the former blacksmith shop.

Part 3: A RETURN TO TRANQUILITY

[Repeated from Dr. Mark's previous section... ] Apparently this scene was one of his favorites. It was not only one of his earliest paintings, it was also one of his last. He made versions of the scene in at least three of his four studios. Some two decades after Redgate studio burned, I can remember RSW asking me to pull out one of the original paintings from the back storage room. This was during cold winter days of World War II, when he could not paint outside. He would place it under the natural light from the North window of his Southwick Studio, and then make a duplicate canvas. I am aware of at least two oil paintings made in this manner.

The advantage to adding all of the windows to the

The advantage to adding all of the windows to the

converted blacksmith shop

is the massive hearth and its

additional "teachers stove" to warm the space adequately.

[Continued from Dr. Mark's essay... ]

...I would keep the fireplace going full blast to make sure the studio was comfortable enough for him to keep working.

Lena would bring out hot coffee. On especially cold days I would have to load up the schoolhouse stove (which stands

just on the right of the fireplace) and keep fire logs burning in it also for extra heat. Most of these paintings were

done when he was also suffering a lot of pain and shakiness. He often had to hold his right painting hand at the wrist

with his left hand to keep it steady. There was nothing either he, nor we, nor I guess any doctor, could do for this.

Usually, his FM radio was playing classical music softly in the background.

Evening Mists, c. 1945

Evening Mists, c. 1945

Made in the Southwick Studio two

decades after the Redgate fire from

versions made post-fire.

Tranquility, c. 1943

Tranquility, c. 1943

Made in the Southwick Studio two decades after the

Redgate fire

from versions made post-fire in the Hiram Woodward Studio.

It was not common for Robert Strong Woodward to copy paintings such as this. There were

times that this was done when he created a painting for sale on the west coast. He would then create a duplicate for

sale locally. Another reason he would copy a painting is when he created a painting that was not acceptable to him.

For reasons known only to him, he would mark the painting with a purple "D," and place it in the back storage room.

Sometimes years later, usually during bad weather, he would pull out this painting and copy it, fixing whatever was

unsatisfactory to him. Then the original would be destroyed. (Please see the essay on Purple "D" paintings.) Finally,

there were several examples of a scene that simply worked so well, that he copied it several times.

This is the case with the series of paintings in this essay, as well as

those known

as Through October Hills.

734.png?url=../Gallery/photos/mountain_meadow(24)734.png)

Mountain Meadow, c. 1944

Mountain Meadow, c. 1944

This painting is the last of four very similar paintings made

made between 1939 and 1944. It was mistakenly believed to be

Through October Hills (c. 1943), for many years. They are what

RSW called "composite" paintings where he took scenes of

multiple subjects from other paintings and assembled them

into a scene that is often more romantic than his norm.

Mark Purinton

January 2011

THIS IS THE END OF DR. PURINTON'S ESSAY

ADDENDUM to this THIRD SECTION: by BRIAN, March 2025

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

The Southwick studio from the southeast, with

The Southwick studio from the southeast, with

an exterior view of the artist north window. Around

the corner from that is the little east window. Bet-

ween that and the balcony door is where the artist

had his storage space hidden behind a shelves and

cabinets to maintain a neat, organized aesthetic.

According to Dr. Mark this storage space was chock-

full of paintings well into the 1950s. Many of the

canvases were there because RSW was not satisfied

with them for whatever reason. This is the area Dr.

Mark would pull a canvas RSW wanted to "repaint."

We measured the space once and figured it could fit

as many as 180 stretchers at any given time.

The last section of Dr. Mark's essay is perhaps its best. His observations prompted us today, in 2025, to

put his statements to the test. It was obvious these scenes were a favorite of Woodward's. They first appear very early

in his career. They are the only "Redgate-like" paintings made after his first studio burned. Of the three "Quintessential

Redgate" paintings that exhibited in the Lyman residence ballroom, two of them were Winter Evening Stream paintings (Winter

Silence, seen in addendum 2 and Evening Stream #2 ). Moreover, both of those paintings had "copies" made years after 1926

(we used the term copies lightly- the artist often varied size changing the perspective depending on if the size was

more squarish or rectangular changing the scene in various ways).

Winter Pool (1927) was made from Winter Silence

for Woodward's patron-saint, Mrs. Moore and given by her to her sister as a gift. Evening Stream #3 was made either from

Evening Stream #2 or its sepia print sometime in 1932 for the Deerfield Inn where it hung for three years before exhibiting

a few more times between '35 and 1942. Yet still, in the artist's rising prominence only Winter Silence and Evening Stream #3

are seen in the early 1930s. Winter Silence actually plays a huge role in defining Woodward discussed on its artwork page:

Editor's Notes from the Winter Silence artwork page:

"As Woodward did often in his career

when he made a painting he liked very much, he made another similar painting for one of his benefactors. This is the case

with Winter Silence and Winter Pool. Winter Silence, however, gets the short end of the proverbial stick in Woodward's

mem-ory leaving it out of his painting diary entirely despite the fact that at one point Winter Silence becomes a critical

feature of his promotional material from 1931 to 1935. Actually, because of this we can argue Winter Silence is his MOST

referenced artwork in print with an astounding eleven articles linked to and mentioning the painting without it even hanging

at the exhibit the article was referencing!" [second most is

Keach's Stove]

The Southwick Hearth with its accompanying teachers stove.

The Southwick Hearth with its accompanying teachers stove.

While the studio does have heating, with all the windows RSW

had added and no insulation, the small stove or hearth could

easily make up the difference and add an old-fashioned feel.

When the early 19th century blacksmith shop was converted to

the artist studio it had to be raised about 5' and to support

the weight, a giant block of concrete was poured under it...

Woodward not only forgets Winter Silence, a 1926 First Prize winner at the Springfield Art League's special fall exhibition a month before the Lyman show, but ALSO mixes it up with of all paintings, it spawned, Winter Pool in his painting diary. But this does not change the fact that Winter Silence was a critical painting featured in the Boston Herald's special Rotogravure section, a few months after winning a gold medal at Boston's Tercentennial Celebration event for New England Drama and its caption was quoted and picked up by the news services and used 9 times in articles about exhibits the painting itself did not exhibit. It is quite rare to discuss a painting not being exhibited.

Evening Stream #3 is the only Winter Evening Stream painting to be made in the early 1930s, however, it was made either from the 1924 painting or its sepia print image. It also appears to have been made for the Deerfield Inn where it hung for three years (1932 to 1935). After that, it was sent to the Myles Standish hotel in Boston, the Westfield Athenaeum in '38, out to California to hang in long-time friend, Harold Grieve's gallery in Los Angeles for a couple years, and finally back to Boston for the grand finale of the Myles Standish hotel before it closed for good. Each location it was sent to was special to the artist indicating its importance to him.

A side by side comparison of Evening Stream's scene reversed next to Winter Pool.

A side by side comparison of Evening Stream's scene reversed next to Winter Pool.

OH, AND GET THIS... it turns out that Evening Stream is reportedly a reverse image of Winter Silence/ Pool. Same scene, just flipped! This was stated in his painting diary entry for the canvas,

"One of my early paintings of a subject matter I often

used from my first studio Redgate which burned. A large one 36 x 40 [sic] of the same subject, or similar subject

(but reversed) which I called Winter Pool,"

... and even in this instance completely forgets the more accomplished Winter Silence. It is NOT exact. The rocks in the stream are in different locations but the beech trees and pool shape is the same, making it a composite painting of sorts...

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

THE END OF THE THIRD SECTION ADDENDUM

BRIAN'S ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY...

The Torii Gate

The Torii Gate

"Do let me know when you leave for Japan."

An excerpt from a postcard sent by an unnamed

friend in Idaho three weeks before RSW's accident.

Introduction

Dr. Mark recognized that Woodward's Winter Stream Paintings were different than even the dusky wooded interiors the artist made from the rear of his Redgate studio. It is all so symbolic I could write a book on it. We believe the name Redgate is an homage to "the sacred structure of the Japanese Shogun and Buddhist religions called the Torii Gate. To pass through a Torii Gate is:

"to enter 'sacred ground.' They stand

as guardians in front of all temples of worship. Woodward greatly admired Japanese art and culture and

studied Hindu and Buddhist philosophies by his own account."

From our essay on

The Evolution of the Window Picture Painting, part 1

This is not some remote concept to Woodward; he lived just a couple of blocks from Los Angeles' Little Tokyo neighborhood in 1906, just months after the San Francisco earthquake displaced thousands of Japanese people who migrated to LA. At that time, the City of Angels had the largest population of Japanese outside of Japan. On the day of Woodward's terrible accident, we believe that one of the reasons he and his friends started traveling before dawn to catch the Alpine train to get back to the city before the big Labor Day parade began was to also go to the first Japanese Cultural Festival being held later that same day in Venice Beach. We also have a letter from a friend asking Woodward to "Do let me know when you leave for Japan," In his estate remains a Japanese print on iri-rice paper with a label from a shop in Los Angeles a couple blocks from Westlake Park where the artist made an oil painting in 1908.

The Portal, 1919, 50" x 40"

The Portal, 1919, 50" x 40"

Its name alone indicates the entrance to

something, perhaps other worldly. We

have quite a bit of evidence that the

artist was very spiritual and meditative.

The fact that Woodward is making these paintings of the woods just behind the studio figuratively suggests that the artist passes through the Redgate Studio "to enter sacred ground," making it also quite literal. If there is anything one needs to know about Woodward, he is more than meets the eye. He loves elevating and marrying the literal with the figurative. The alchemical marriage of the opposites. He is incredibly complex in a plain package, focusing on simple things, yet he elevates them nonetheless. These are all key qualities to the values and principles of art in the East. The man is very intentional when it comes to such things. At the same time, while intentional, there are always elements outside one's awareness. This line blurs for us when trying to pinpoint when he is aware and when he is not, it is most likely both sharing the same space.

Evening Mists, 1945, 30" x 25"

Evening Mists, 1945, 30" x 25"

A painting reportedly "re-painted" from an

earlier, but "technically imperfect" canvas.

Since no paintings survived the Redgate fire

this suggests it was made post-1922 or later.

Woodward's dusky wooded interiors share some qualities with his Winter Stream Paintings. Both indicate a transitional phase of entering an unknown future. Usually, entering the woods as night approaches is about as scary as it gets, which is why it is used in movies quite a bit as a device to build tension. Just the thought of it is enough to invoke dread in many. Because one can only see so far in the woods, they also represent the immediate or present moment-- what is near. However, where the wooded scenes are an unknown future, his winter stream paintings are latent or quiescent. Its quantity is not unknown; its presence is felt by the weight of its pressure, seen in the ice-dammed pools building to such depths. Those streams are generally not that deep. The waters are obstructed. However, this will not always be the case. There will be a transition when the snow melts and the stream flows again; when it does, it will nourish the upcoming planting season. Those pools of water will drain into the meadow nearby. So these paintings suggest some sort of inevitability...

Evening Tranquil Hour, c. 1924

Evening Tranquil Hour, c. 1924

This painting exhibits at the 1924 Stockbridge (MA)

Public Library. It is one of only seven known paint-

ings to exhibit between Jan. 1923, and Nov. 1926.

That is a span of 34 months or nearly 3 years.

The best thing about latent potential is the inherent possibility that comes with it. Potential can go unfulfilled or mishandled. Any misstep could dissipate the building energy or ruin its momentum. Symbolically, these paintings, while seemingly serene and peaceful, portray some very complex motives, one in particular being stress. Woodward is seeking calm, but the tension is there just below the surface. There is also the idea of an approaching critical mass. In psycho-logical terms, critical mass refers to "the point at which a certain number of people or a specific type of behavior/idea is present, leading to a self-sustaining change or trend, often described as a 'tipping point'." [ fs.blog] This point will be essential when we lay out the pattern in which these paintings appear throughout the artist's career. So, the wooded interior is about entering an unknown, and the Winter Evening Stream paintings are about Woodward's inner struggle to remain calm under the stress and pressure of a transitional phase. Phase transitions always occur with an oomph. There is no intermediate phase between a liquid and a solid. All of the conditions must be present before water turns to ice and vice versa. It is, or it is not... It is a razor's edge between fulfilment and the unresolved.

Miyamoto Musashi, warrior turned artist, (1584- 1645):

"In strategy your spiritual bearing must not be

any different from normal. Both in fighting and in everyday life you should be determined though calm. Meet the

situation without tenseness yet not recklessly, your spirit settled yet unbiased. Even when your spirit is calm do

not let your body relax, and when your body is relaxed do not let your spirit slacken."

From the website: TALIALEHAVI.com

LG.png?url=photos/Cowell/cowell_joseph1924(MassArt)LG.png)

Woodward friend and classmate

Woodward friend and classmate

at both Bradley and the School of Fine

Art, Boston- - Joseph Cowell from the

1927 Mass. School of Art yearbook.

Up to this point in Woodward's life, before the Redgate fire, all of his greatest tragedies and disappointments are his own doing. While accidents, he shares some of the blame for his misfortunes. Simply put, his carelessness with a revolver led to the accidental discharge of the gun when removing his sweater. The most basic reason he did not last until Thanksgiving at the School of Fine Art in Boston is that he and his good friend from Bradley, Joseph Cowell, agreed to see to his daily care and routine without a nurse. Naively believing the two young men could pull it off... it did not last. Woodward was very sick and was sent to be with family in Buckland, and never returned. We can't even really call it home because he had lived in California and Illinois for six years prior going to Boston.

A portrait of William Macbeth by

A portrait of William Macbeth by

Stephan Douglas Volk from the

collection of the Brooklyn Museum.

We believe Woodward is aware of his part in both incidents. We also believe that he never really

intended to be a professional painter; it was his last resort or as it is put in a featured profile on him by

Springfield art critic, Jeannette Matthews, in May of 1928, "An active life denied, he turned his energies to

the field still left open..." explaining why he began to paint. The profile was taken from an interview Matthew

had with Woodward from a tea reception in his honor sponsored by the Junior League.

There is considerable evidence indicating

that Woodward, a bibliophile, wanted to be an illustrator and work in publishing. The truth of the matter is that

being a professional painter was the only business model that works for an artist living in rural New England.

To be an illustrator meant being in close proximity to editors and publishers and networking. His insecurities

about painting were evident when he went to prominent artist Gardner

Symons for his opinion of his work- was it good enough? So here Woodward is a whirlwind of early success,

a national prize, his patrons pressuring the most famous American Art gallery owner, William Macbeth, to give

the freshly minted star his own One-man show in the mecca of New York City. He is clearly still uncertain of

his talents and abilities. It is all pressing on him and coming too fast. This is when he begins making the

Winter Evening Stream paintings, which reappear at every critical point of his career thereafter...

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Analysis

Winter Mist, c. 1920 is thought to be the

Winter Mist, c. 1920 is thought to be the

first winter woods interior featuring water. It is

essentially the same scene as Out of the Mist

but farther back. Note the Beech Trees that

dress the scene with its very vibrant leaves.

It also adds to their importance to Woodward's

perspective as the Beech appears more in his

work than any other. For more on its meaning

we suggest you look it up. For now we want to

point out two things: (1) the word "book" is

believe to be derived from the Beech Tree!

(2) And that the first paper-like material was

made from its bark in many ancient societies.

So Woodward begins painting the Winter Evening Stream pictures to cope with the stress of the new expectations and pressures put on him due to his success. He returns to them after his Redgate fire, perhaps to help him grieve the loss of his much loved first studio (and, by extension, the 300 rare collectible books it held). As a matter of fact, by our count, he makes more post-fire Winter Evening Stream paintings than before the fire. Some of these canvases sit in his storage space for being technically subpar for whatever reason for 20 years. The question now is, does the pattern hold up? Does Woodward turn to the Winter Evening Stream paintings at other, pregnant, stress-invoking, critical times in his career? The answer is he does...

I have already given you enough to understand their original and how Woodward returned to the Winter Evening Stream paintings after the Redgate fire. Still, it is important to remember that his career did not kick back into gear until December 1926, a week short of four years to the day after his Redgate fire. He officially has his one man show, but it is NOT at a gallery. It is held in the second floor ballroom of the home of Mr. & Mrs. Ronald Lyman on Beacon Street in Boston. The Lymans are neighbors of Woodward's greatest advocate and benefactor, Mrs. Mary "Minnie" Eliot. The first painting is bought by another Beacon Street neighbor and Eliot friend, art collector John Spalding. It is Woodward's first professionally made Window Picture painting, literally named: The Window; a Still Life and Winter Scene.

When said out loud, it all feels very staged or put on. So we had to ask ourselves, why go to such lengths? The answer we are afraid is that part of the fallout of the Redgate fire was that not only was Macbeth furious at the whole episode, he let it be known. We know he held a grudge and did not give Woodward his first show in his gallery until late in 1931 well after he re-established himself with great success. We think this all indicates that no gallery was willing to take a risk on Woodward, and so Minnie and probably Mrs. Ada Moore, as well, conspired to kick-start his career again. After the Lyman show is where we pick up the rest.

⮟ 1927 to 1937

The years of Woodward's ascension as he works his back from disaster he makes only one "new" Winter Evening

Stream painting (Winter Pool) before 1931 and

that is for a special patron and its inspiration exhibits a few times. Also, it is not new but rather a slightly

larger and squarer version of Winter Silence.

The other Winter Evening Stream canvas is made after he wins the 1930 gold medal at the Boston Tercentennial

exhibition and is also made from an earlier painting

Evening Stream #2 but almost the same painting. Both original paintings hung at the Lyman show and so

they are merely carry-overs of the previous 1923 to 1925 period. Evening Stream #3

to hang in the Deerfield Inn for a few years. It was not uncommon for him to do this. Other examples are paintings

that hung in the Myles Standish Hotel lobby in Boston, Sweetheart Tea House Restaurant in Shelburne Falls and

Weldon Hotel lobby in Greenfield. All during the same period of time. So technically, as Woodward's career is

going well and ascending, he makes only one true Winter Evening Stream painting and it is a copy of a previous one.

Winter Window, 1937

Winter Window, 1937

This is the first "Window Picture Painting"

made in 1937 but the second one made at his

new Southwick Studio. The first was made in

1935 from the studio's Artist North window

christening the new place if you will... but

it was another 2+ years before he started to

make them consistently to end of his career.

⮟ 1937 to 1945:

After surviving another tragic fire in July of 1934, Woodward, for many reasons, retreats to home and safety

as his popularity continues to rise. The fire does not hurt his reputation like the first one did. However, he did

have to make it publicly known he was still, "open for business" and that no paintings were lost. This is the absolute

height, or pinnacle of his career. He has a lot going on in 1937... he wins an award in Albany, NY, his work is

hanging with some of the greats of all time in a special exhibition in Los Angeles, and he has a looming commission

to paint- a series of canvases of historic and early American churches and fine homes for the Mabel B. Garvan Collection

at Yale University. The Garvan Collection is the finest of it kind and still thrives to this day where his painting

Enduring New England still remains as one

of less than 250 paintings of over 2,000 originally purchased to start the collection.

It is now more than

a decade that Woodward has worked on building and establishing himself as one of the best landscapist in the county

but we believe he is growing tired. We believe he finds himself conflicted as to what he wants to do with the rest

of his career. It appears that 1937 seems to be the catalyst of this impending change. We think there are several

factors at play but one above all else is the events occurring around the world with Germany and Japan both ruthlessly

invading countries without provocation. The artist could not reconcile how a culture he so admired could be so

brutual. but perhaps is was Mr. Garvan's death just 20 days after buying Enduring New England leaving the

artist on the hook for the other paintings under commission. The catalyst is that Garvan was just ten years older than

Woodward. The death was sudden and unexpected. Garvan would not get to enjoy the success of his achievements, so maybe

Woodward began to reevaluate his priorities. We did some accounting...

Enduring New England, c. 1930

Enduring New England, c. 1930

Note the year this was made. The same year he won

the Boston Gold medal! The Year Winter Silence

appeared in the Rotogravure section of the Boston

newspaper... the year that changed everything.

We found

that in the years between 1937 and 1945, Woodward made more than half of all his Window Picture paintings, as well

as his Beech Tree paintings. He also made most of his "composite" paintings (12) during this period of time, and

"re-painted" as many as 12 paintings from the 1920s kept his storage space. More than half of his paintings were made

from his home between these years. Woodward also bought the Heath property in 1938 and began building his 'pasture

house' finishing it by 1940. He painted numerous canvases in his new remote studio/cabin.

In the same years

the artist would also paint 6 paintings of the Charlemont bridge after it is washed away by the 1938 hurricane that

devastated New England. Those paintings were also made from an early painting he made in the 1920s. He made his

first still life painting in more than 6 years, (Chinese Lily ).

There are another 5 or 6 paintings he made from one window or another inside his Southwick home and studio windows

(that are not window picture paintings). Finally, there are several canvases made on the street he lived on or just

around the corner. It is clear that he is staying close to home and while you cannot say he took it easy (he averaged

just about the same amount of paintings per year as his career average of 18) he certainly made it easier on himself

by traveling less.

Yet still, at the very end of this period, in 1944 and '45, he repainted two Winter Evening

Stream canvases from two 1920s paintings that sat in storage... ending this uneven period and transitioning his to his

next new phase.

A Hill Road, (Award Winner) 1946

A Hill Road, (Award Winner) 1946

Made from Heath, farther north of the pasture house.

Buckland school teacher Miss Mabel

Buckland school teacher Miss Mabel

Raguse in her apartment in Shelburne

Falls, MA beneath From a May Hill. Her

relationship to RSW is very sweet

- a must read.

⮟ 1946 to 1950:

Another hiatus from the Winter Evening Stream paintings. It is also Woodward at his esteemed best. His paintings

from this time, as his health declines, are arguably among the best painted works. He would win as many awards and

prizes in this period of time as he did from 1930 to 1937 or 1919 to 1926. Most of them Window Picture Paintings and a

Beech Tree painting that would end up hanging in the U.S. Embassy in London! (see:

Snowing on the Hill) This five year period is the only time in his career without a known Winter Evening

Stream painting.

Evening Woodland, sepia, c. 1951

Evening Woodland, sepia, c. 1951

The second to last Winter Evening Stream (WES) RSW

made before retiring. It was made before the last WES

painting and is the third last of his career. He ended his

career with two WES canvases and a Window Picture

painting seen below ⮟ This sums up their relevance...

⮟ 1951-1952:

With the end clearly in sight now, his health deteriorating (he travels to Boston routinely from 1949 to '51 to

see doctors), and his hands are shaking almost too hard for him to control, Woodward again returns to the special Winter

Evening Stream paint-ings making two back-to-back can-vases,

Evening Woodland, Woodland Mystery

of the same scene with the latter going to his close friends, the Rhoades in the winter of 1950- '51, and his last

painting right after is, Spring Window which would go to the artist most appreciated client, life long teacher,

Miss Mabel Raguse.

Spring Window, 1951

Spring Window, 1951

Note the year this was made. The same year he won

the Boston Gold medal! The Year Winter Silence

appeared in the Rotogravure section of the Boston

newspaper... the year that changed everything.

The Winter Evening Stream paintings all appear at these very specific times in his life. The times when he was perhaps at his most vulnerable and uncertain, maybe in-secure, or he was transitioning to a new phase of his life that has their own kind of emotional anguishes yet also holds their own possibilities. The pattern is apparent. When he was working to achieve something with a clear objective. From 1927 to 1943, only two new canvases were made and they were similar to earlier painting and created for a special reasons. The second respite, 1946 to 1950, coincides with the end of WWII and the years he makes half of his Window Picture Paintings, a few of which won prizes and awards. Equally important is the fact that paintings made between 1946 and '50 are among his most mature and sophisticated clear-headed canvases in both technique and composition of his career during his physical decline. We feel strongly the Winter Evening Stream paintings served as a method of meditation and comfort to the artist. The subject and scene offers tranquillity under pressure of building potential or one can say inevitability. It was his "safe space" and he was also a romantic fool at heart and when the end nears one tends to remember where it all began in appreciation of the journey. It is the journey that is remembered with fondness.

Brian C. Miller, July, 31, 2025

A CHART OF RSW'S WINTER EVENING STREAM PAINTINGS FROM FIRST TO LAST