Edith Storer Rhoades and Winfred Rhoades

"The Self You Have to Live With"

It appears that Robert Strong Woodward was friends with Edith Storer and only became acquainted with her husband, author Winfred Rhoades, after their marriage. According to the painting diary, prior to 1934. the painting Autumn Flame was "bought by Miss Edith Storer of Waltham, now Mrs. Rhoades of Lane's End, Sudbury, Mass." Later entries, such as Summer Peace have the comment "Bought in September 1945 by Mrs. Winfred Rhoades (Edith Storer) and hung perfectly in her rare old house (built in 1724) at Chestnut Hill, Mass, 521 Hammond Street, a rare example of perfect placement."

"The Self You Have To Live With"

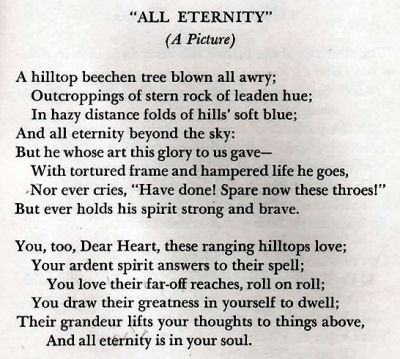

All Eternity by Robert Strong Woodward

Poem by Winfred Rhoades about the Robert Strong Woodward

painting All Eternity published in the book "Tributes"

"Tributes" by Winfred Rhoades, 1950

A book of 55 poems of beauty and love dedicated to his wife

"Further Tributes" by Winfred Rhoades, 1959

more poems dedicated to Edith Rhoades

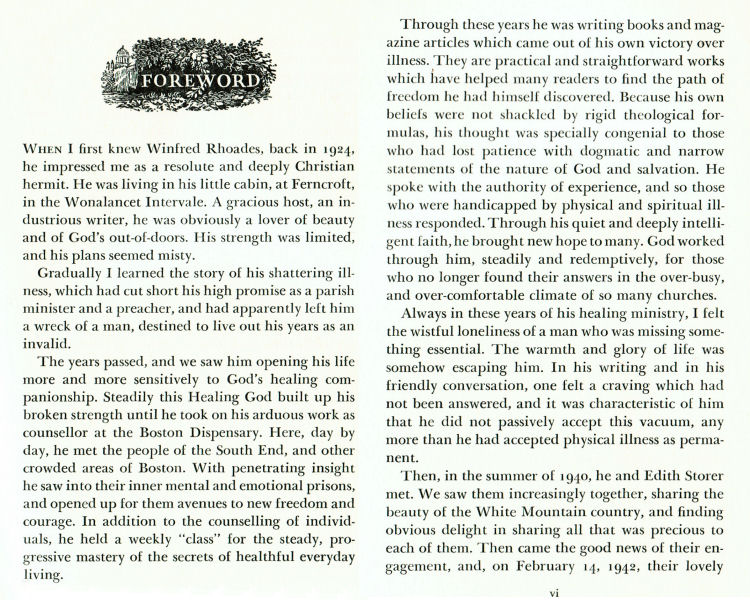

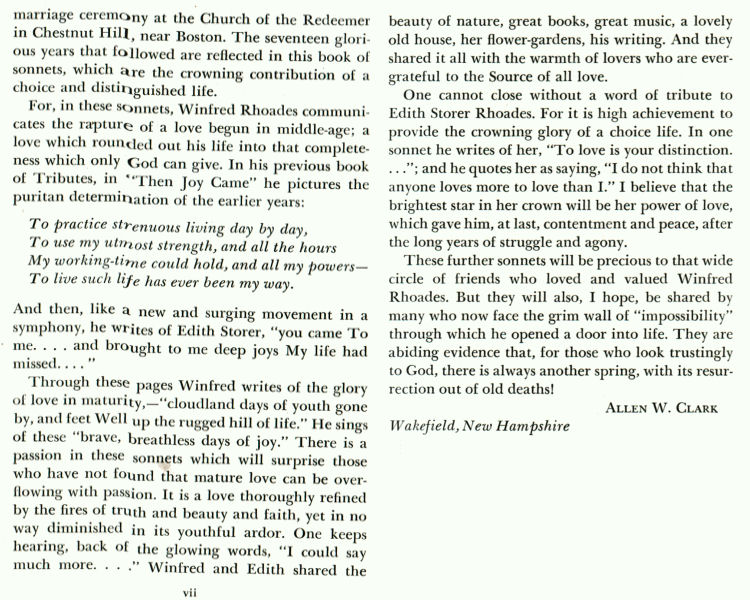

Preface to the book "Further Tributes." by Allen W. Clark

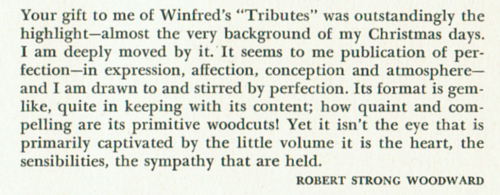

In appendix to the book "Tributes," there is a comment from RSW.

Mr. and Mrs. Rhoades are known to have owned 4 paintings including:

Autumn Flame sold in 1942.

Woodland Mystery sold in 1942.

All Eternity (previously named The Silver Sky) sold in 1945.

Summer Peace sold in 1945.

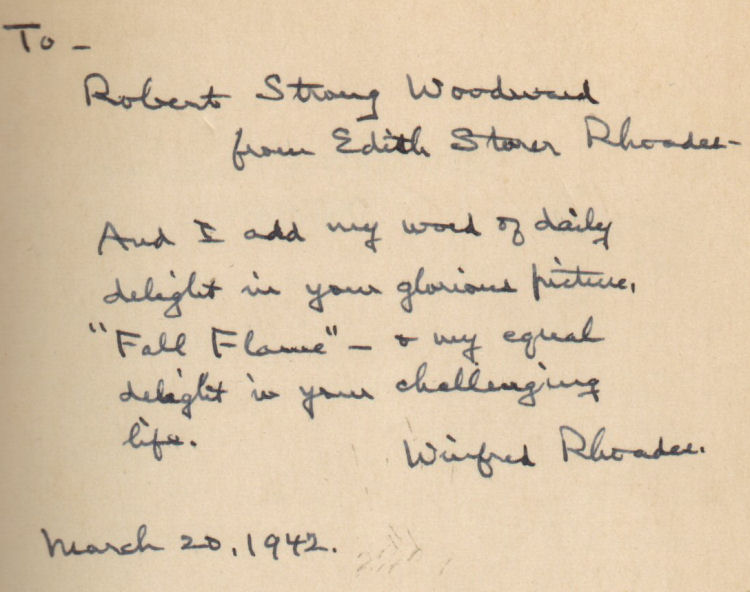

Personalized note to RSW by Edith and Winfred Rhoades inside the front cover of "The Great Adventure Of Living"

To - Robert Strong Woodward from Edith Storer Rhoades -

And I add my word of daily delight in your glorious picture, "Fall Flame" (sic. Autumn Flame) -

and my equal delight in your challenging life.

Winfred Rhoades.

March 20, 1942

And I add my word of daily delight in your glorious picture, "Fall Flame" (sic. Autumn Flame) -

and my equal delight in your challenging life.

Winfred Rhoades. March 20, 1942

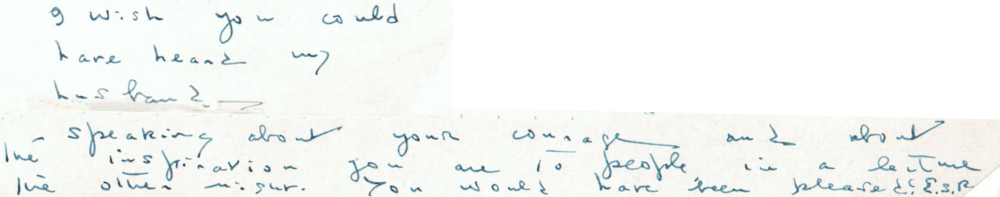

Handwritten note from Edith Rhoades on the cover page of "The Great Adventure of Living" which was given to Robert Strong Woodward in 1941.

"I wish you could have heard my husband speaking about your courage and about the inspiration you are to people in a lecture the other night.

You would have been pleased. E. S. R".

(Edith Storer Rhoades)

"Meeting the Challenge Of Life," 1939

"The Great Adventure Of Living," 1942

Winfred Rhoades' list of publications include:

"Frederick Ernest Emrich, Lover Of Humanity" (1933)

"Cure By Faith", a sick mind makes a sick body (1937)

"The Self You Have To Live With " (1938, 1947)

"Meeting The Challenge Of LIfe" (1939)

"Have You Lost God?" (1940, 1950)

"The Great Adventure Of Living" (1942)

"Finding God More Vitally" (1948)

"Tributes" (1950)

"To Know God Better" (1958)

"Further Tributes To Edith Storer Rhoades" (1959)

Three quotes attributed to Winfred Rhoades:

"A person is really alive only when he is moving forward to something more."

"Life's greatest achievement is the continual re-making of yourself so that at last you know how to live."

"Not the state of the body but the state of mind and soul is the measure of the well-being of each of us."

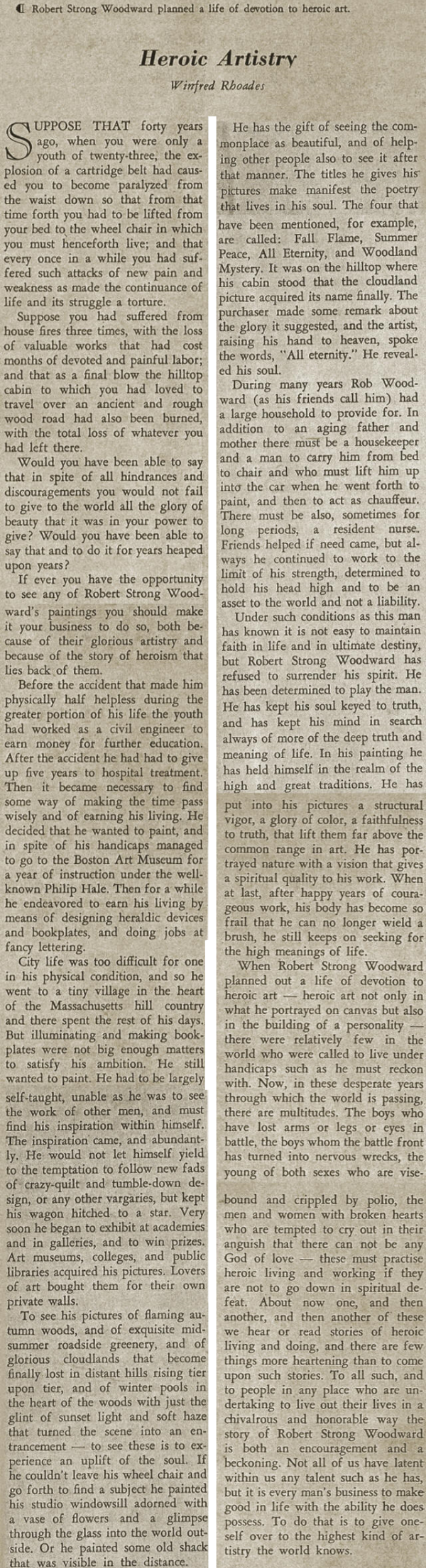

"Heroic Artistry" by Winfred Rhoades

Pages from "Clear Horizons," Winter, 1954

"Heroic Artistry" by Winfred Rhoades

Suppose that forty years ago, when you were only a youth of twenty-three, the explosion of a cartridge belt had caused you to become paralyzed from the waist down so that from that time forth you had to be lifted from your bed to the wheel chair in which you must henceforth live; and that every once in a while you had suffered such attacks of new pain and weakness as made the continuance of life and its struggle a torture.

Suppose you had suffered from house fires three times, with the loss of valuable works that had cost months of devoted and painful labor; and that as a final blow the hilltop cabin to which you had loved to travel over an ancient and rough wood road had also been burned, with the total loss of whatever you had left there.

Would you have been able to say that in spite of all hindrances and discouragements you would not fail to give to the world all the glory of beauty that it was in your power to give? Would you have been able to say that and to do it for years heaped upon years?

If ever you have the opportunity to see any of Robert Strong Woodward's paintings you should make it your business to do so, both because of their glorious artistry and because of the story of heroism that lies back of them.

Before the accident that made him physically half helpless during the greater portion of his life the youth had worked as a civil engineer to earn money for further education. After the accident he had to give up five years to hospital treatment. Then it became necessary to find some way of making the time pass wisely and of earning his living. He decided that he wanted to paint, and in spite of his handicaps managed to go to the Boston Art Museum for a year of instruction under the well known Philip Hale. Then for a while he endeavored to earn his living by means of designing heraldic devices and bookplates, and doing jobs at fancy lettering.

City life was too difficult for one in his physical condition, and so he went to a tiny village in the heart of the Massachusetts hill country and there spent the rest of his days. But illuminating and making bookplates were not big enough matters to satisfy his ambition. He still wanted to paint. He had to be largely self-taught, unable as he was to see the work of other men, and must find his inspiration within himself. The inspiration came, and abundantly. He would not let himself yield to the temptation to follow new fads of crazy-quilt and tumble-down design, or any other vagaries, but kept his wagon hitched to a star. Very soon he began to exhibit at academies and in galleries, and to win prizes. Art museums, colleges, and public libraries acquired his pictures. Lovers of art bought them for their own private walls.

To see his pictures of flaming autumn woods, and of exquisite mid-summer roadside greenery, and of glorious cloudlands that become finally lost in distant hills rising tier upon tier, and of winter pools in the heart of the woods with just the glint of sunset light and soft haze that turned the scene into an entrancement - to see these is to experience an uplift of the soul. If he couldn't leave his wheel chair and go forth to find a subject, he painted his studio windowsill adorned with a vase of flowers and a glimpse through the glass into the world outside. Or he painted some old shack that was visible in the distance.

He has the gift of seeing the commonplace as beautiful, and of helping other people also to see it after that manner. The titles he gives his pictures manifest the poetry that lives in his soul. The four that have been mentioned, for example are called: Fall Flame, Summer Peace, All Eternity and Woodland Mystery. It was on the hilltop where his cabin stood that the cloudland picture acquired its name finally. The purchaser made some remark about the glory it suggested, and the artist, raising his hand to heaven, spoke the words, "All Eternity." He revealed his soul.

During many years Rob Woodward (as his friends all him) had a large household to provide for. In addition to an aging father and mother there must be a housekeeper and a man to carry him from bed to chair and who must lift him up into the car when he went forth to paint, and then to act as chauffeur. There must be also, sometimes for long periods, a resident nurse. Friends helped if need came, but always he continued to work to the limit of his strength, determined to hold his head high and to be an asset to the world and not a liability.

Under such conditions as this man has known it is not easy to maintain faith in life and in ultimate destiny, but Robert Strong Woodward has refused to surrender his spirit. He has been determined to play the man. He has kept his soul keyed to the truth and has kept his mind in search always of more of the deep truth and meaning of life. In his painting he has held himself in the realm of the high and great traditions. He has put into his pictures a structural vigor, a glory of color, a faithfulness to truth, that lift them far above the common range in art. He has portrayed nature with a vision that gives a spiritual quality to his work. When at last, after happy years of courageous work, his body has become so frail that he can no longer wield a brush, he still keeps on seeking for the high meanings of life.

When Robert Strong Woodward planned out a life of devotion to heroic art - heroic art not only in what he portrayed on canvas but also in the building of a personality - there were relatively few in the world who were called to live under handicaps such as he must reckon with. Now, in these desperate years through which the world is passing, there are multitudes. The boys who have lost arms or legs or eyes in battle, the boys whom the battle front has turned into nervous wrecks, the young of both sexes who are vise-bound and crippled by polio, the men and women with broken hearts who are tempted to cry out in their anguish that there can not be any God of love - these must practice heroic living and working if they are not to go down in defeat. About now one, and then another, and then another of these we hear or read stories of heroic living and doing, and there are few things more heartening than to come upon such stories. To all such and to people in any place who are undertaking to live out their lives in a chivalrous and honorable way the story of Robert Strong Woodward is both an encouragement and a beckoning. Not all of us have latent within us any talent such as he has, but it is every man's business to make good in life with the ability he does possess. To do that is to give oneself over to the highest kind of artistry the world knows.

Pages from "Clear Horizons," Winter, 1954

There were a group of friends that all associated with each other. Robert Strong Woodward, Winfred and Edith Rhoades, Dr. Lawrence and Marjory Lunt, and Ethel Paine Moors. Dr. Lunt was a close friend of RSW in the early 1900s not long after the gunshot accident that left him paralyzed. Dr. Lunt was a psychiatrist who knew and collaborated with Winfred Rhoades, a mental health expert, psychologist and counselor at the Boston Dispensary.

Marjory Glen Lunt letter to Mr. and Mrs. Rhoades after reading the book "Tributes."

"To us, knowing you two, and your perfect love and life they make intimate and rich reading. They give me courage and faith when I think of them which is often. They are very beautiful. What they must mean to you, Edith, the inspirer of such devoted and exquisite love! The picture it makes of you two--warm and content, and worshipping Beauty, physical and spiritual, your lamps hanging high to light the world around you is heart warming."

Another letter was written by Ethel Paine Moors, wife of John Moors and the owner of the Manse, a large home on Bassett Road in Heath and formally a stop along the Underground Railroad. The Moors purchased the painting From the Manse in Heath.

Letter from Ethel Paine Moors about the first volume of "Tributes."

The book is my bedside reading and lovelier every night. I have no favorites, for I like them all best! No end of love and admiration for that so-wonderful wife, and her so-wonderful poet husband."

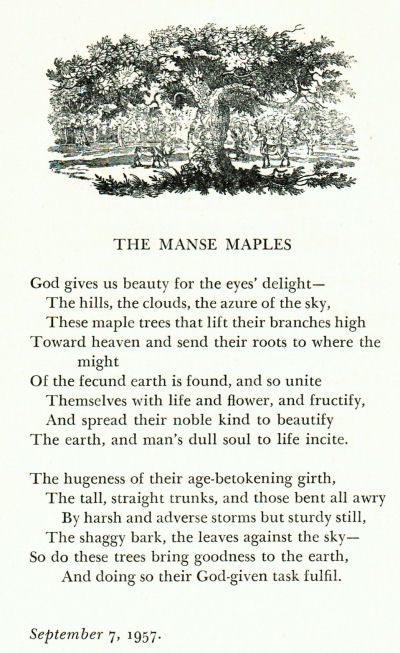

Winfred Rhoades wrote a poem about the maple trees

on the Manse property.

"The Manse Maples," a poem by Winfred Rhoades

Robert Strong Woodward wrote in his diary about his painting From the Manse in Heath:

Painted circa 1930. Painted from the yard of Mrs. John F. Moors, beautiful place in Heath, showing the west view of hills through the tall straight boles of the majestic maples in her yard. Bought by Mrs. John F. Moors of Heath and 150 Fisher Avenue, Brookline, Mass."

Then finally, there is an quote from Alastair G. Maitland published in "The Book of Heath: Bicentennial Essays":

Amongst his (RSW's) closest friends in the town were Mrs. Moors, a prominent Bostonian, who was a summer resident in the Manse on Bassett Road, now the property of James Coursey, and the sisters Flora and May White, who were among the founders of the Heath Historical Society and who owned the present Read and Howland properties near Heath Center. During the thirties the White sisters would occasionally arrange showings of Woodward paintings in a room in the Howland house. Mrs. Moors, like Mrs. W. H. Moore of Pride's Crossing, was among Woodward's principal supporters. One of his landscapes, done on Burnt Hill "Winter Hill to Winter Hill", was presented by Mrs. Moors to Edith Gleason."

Personal note: Edith Storer Rhoades became my patient in the very early days of my medical practice.

LMP/MLP

December 2012