WOODWARD's BOSTON ROMANCE

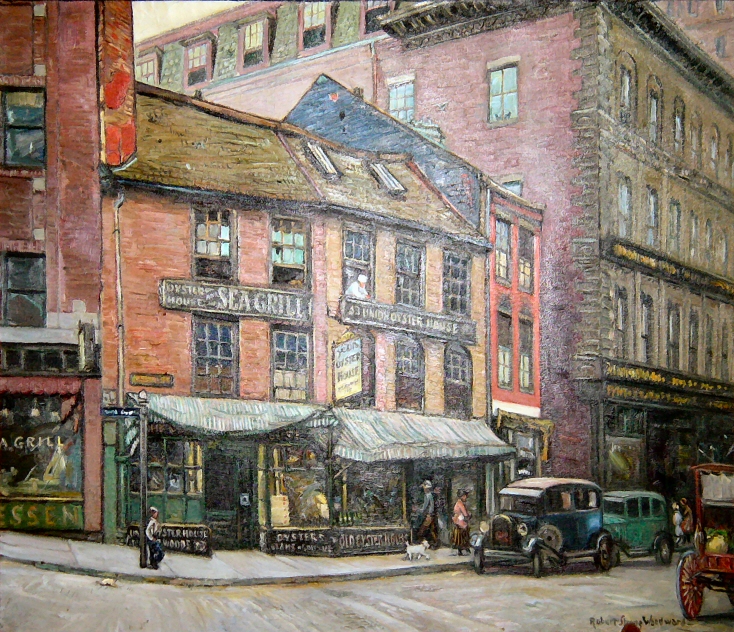

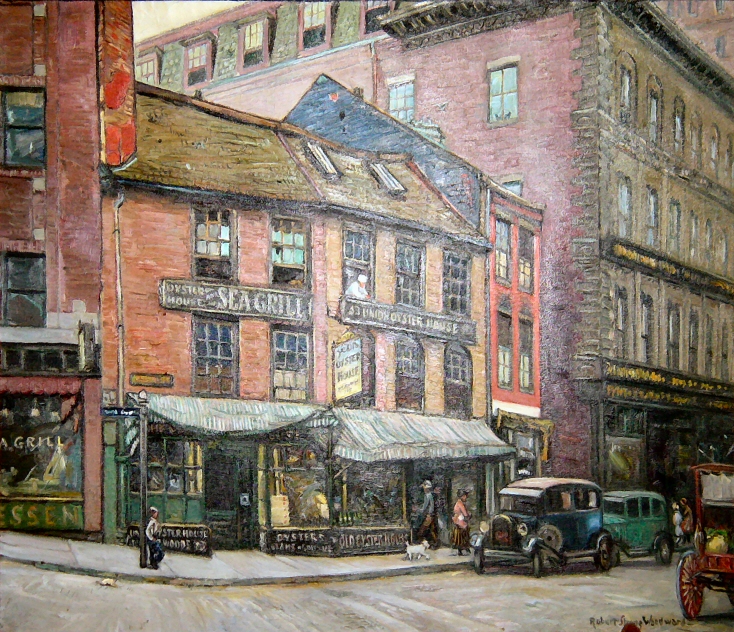

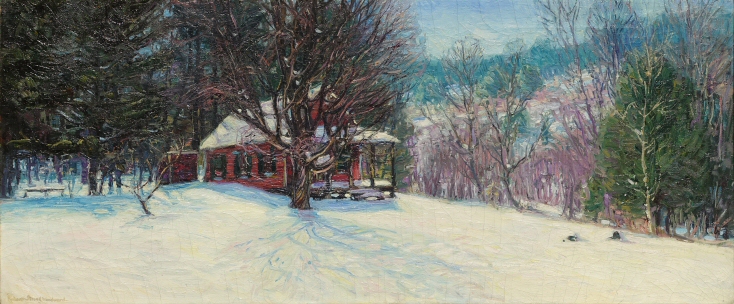

In Old Boston, Oil 1930

THE DREAM: meets with reality

Woodward's history with Boston goes back to his childhood in regard to his desire to study art at the prestigious Boston Museum of Fine Arts School (BMFAS). He often expressed his intent in letters to his childhood friend Helen Ives Schermerhorn despite his father's wish for him to follow in his footsteps and attend Stanford University for engineering (most likely civil engineering). That dream would become a reality when in 1910 Woodward, along with a group of friends, would raise the money on their own to put him on a train from Los Angeles to Boston just before the start of the fall semester. In what was most likely an act of rebellion from his father, who never relented from his desire Woodward went to Standford. He arrived in Boston and moved into a small apartment with friend and Bradley Institute classmate, Joseph Cowell. The arrangement was that Cowell would see to all of Woodward's needs, acting as both nurse and attendant, preparing RSW in his daily required rituals as well as carrying him about when necessary.

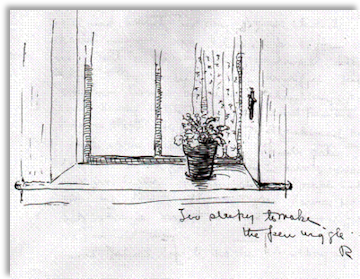

From a card to Helen Ives, a sketch of RSW's

From a card to Helen Ives, a sketch of RSW's

apartment window in Boston. On it he writes, "Too

sleepy to make the pen wiggle. R"

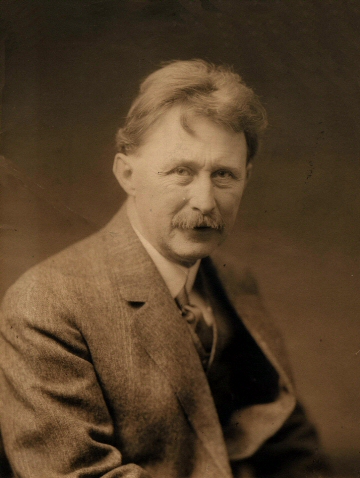

It is almost exactly four years to the day when RSW would suffer a tragic gun accident that would leave him paralysed from the chest down. Though vigorous and strong, RSW would have never been able to do this without the help of others. It is 1910; their apartment is not on the ground floor and does not have an elevator. The sidewalks and buildings do not have wheelchair ramps. Many of the streets are still cobble stone and Boston is one of the most congested cities in the country. Woodward would study under American artist Phillip Leslie Hale,, brother of the famous female artist Ellen Day Hale.. Crowell, the same age as RSW but an upperclassman and closer to finishing his studies, believed in Woodward so much he felt the sacrifice worthy. He reportedly gave up his year to aid his friend. The closeness, mutual respect, and affection between these two young men cannot be overstated. However, in the end it proved to be too much for both. Woodward would soon leave the school, his apartment and friend sometime just before the Christmas break never to return. It would not be the last time Boston would fail to meet his expectations. Nonetheless, when in the most need, Boston would make three significant contributions to his career... this is the story of Woodward's relationship with Boston.

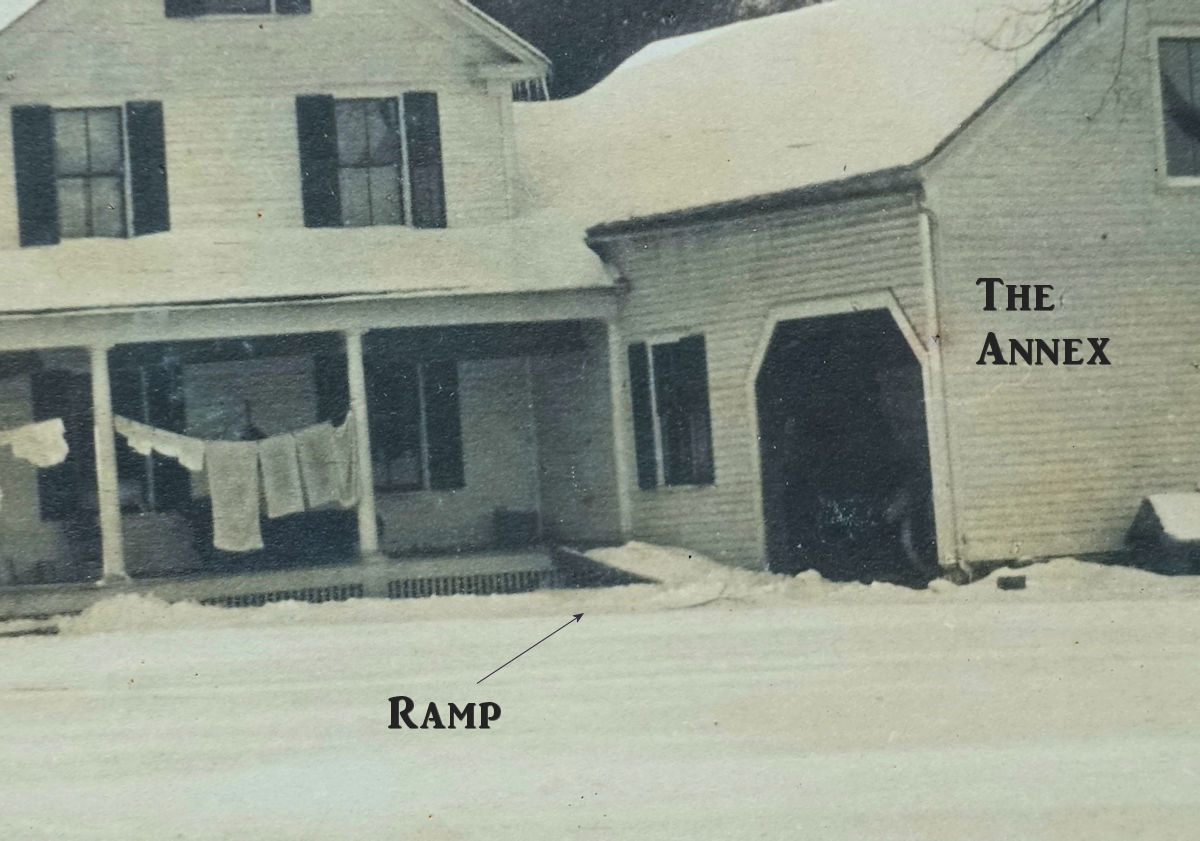

Above is an old picture of the ramp still attacted

to the porch and the annex showing a garage door with

car.

However, we do not believe this was always the

case. Below is a picture of the porch and annex today

looking much as it did when RSW lived there.

REGROUPING: A career as an Illustrator

Woodward would leave Boston and return to the home of his aunt Tella and uncle Bert in Buckland, MA where his grandparents now lived among a large household of kids and farm workers. A place he visited nearly every summer of his childhood growing up. It would be unlikely he would return to LA with his parents after what must of felt like a failure to him in Boston. What's more is that at this time, any city would be a difficult and cost prohibitive prospect for a man in his condition. This eliminates Peoria, IL, the only other home he knew and Chicago f or which he appeared to be quite familiar. Buckland was an ideal situation for him... the farmhouse had an annexed area close to the ground that he could come and go. The annex was classically old and rustic which we imagine he preferred. His family built a ramp to the front porch of the house for him to navigate. In addition, the farm had an old dairy shed right off the main road to which his family offered for him to convert into an artist's studio he affectionately called Redgate.. Furthermore, the rural areas of this area had no sidewalks or tall buildings and high traffic both pedestrian and vehicle. Buckland was not only his best option but may have been his only. Woodward's plan was to begin a career as an illustrator of bookplates, illuminations and other heraldic devices used in the booming print industry of the day (much like the booming digital age of today).

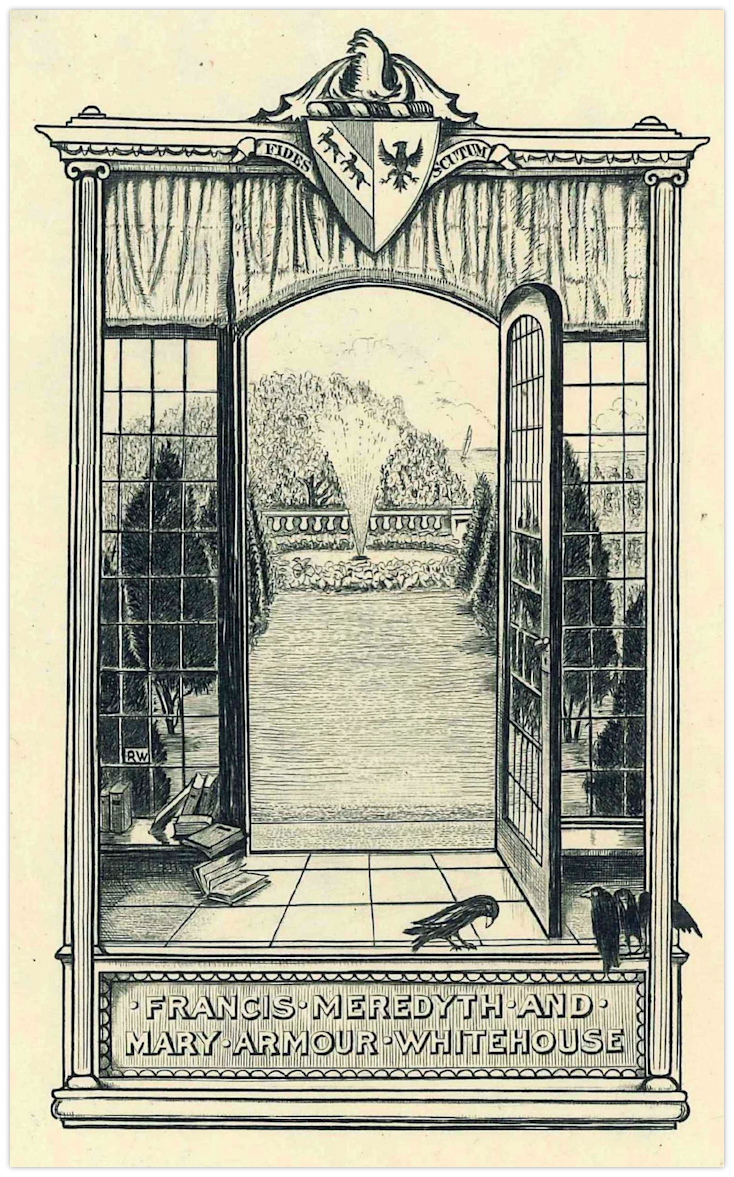

While the idea was a good one, its business model would prove too arduous to sustain. It is a demanding task to sell your "services" from a rural area when print & publishing is primarily a city-based industry. Woodward did have the benefit of Boston area plate engraver John Edison Elwell. They did collaborate on projects but RSW's pipeline to Chicago and to a certain extent, NYC would be significant. It is unclear to us how RSW secured such important clients. One client, prominent Chicago architect Francis Merdyth Whitehouse did retire to Manchester by the Sea (MA), and had Woodward create the bookplate for his estate Crowhurst. We only have a handful of examples of RSW's Illuminations, and it is not clear if they were sold from his studio, or through local general stores and/or made into prints for resale. By 1916, after reportedly finding a grey hair, RSW set his sights on pursuing his dream of becoming a landscape artist and began painting in oils.

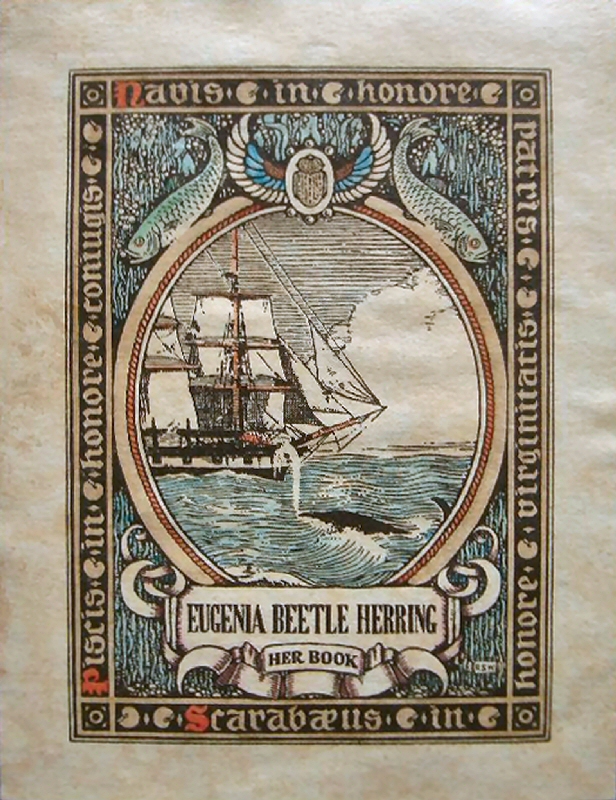

Eugenia Beetle Herring, Bookplate

Whaling Heiress, New Bedford, MA

This bookplate is one of the more remarkable

examples we have. It is the only color print

bookplate we know of, as well as, it being one of

the more dramatic and expressive examples. The

nautical themed artwork is also a rarity for RSW.

Woodward in his phaeton buggy (1921) with

Redgate showing to his right and the Wells

Farm over his left shoulder. RSW did move

out of annex and down the road to the

Burnham Cottage on the property of what

would later his second home & studio.

the small Hiram Woodward Farm

After dedicating a year or more to paint in oil, Woodward sought out prominent local naturalist artist Gardner Symons of Colrain (MA), bringing a number of pieces for him to see and give RSW a professional opinion. Symons was impressed with Woodward's work. He encouraged RSW to submit his paintings to the 1918 National Academy of Design's (The Academy) annual exhibition held in April, New York City (NYC). Six months later, RSW enters two paintings: Fall Fires and Hill Farm, to the inaugural "New England Artist" exhibition at the Boston Art Club. The show's inception stirred quite a bit of controversy because the Boston AC was staunchly exclusive to "traditional European styled art." In an article from the Boston Evening Transcript, in review of the show mentions RSW. His work is described as, "...captivating in its uncompromising veracity, its portraiture of a novel and beautiful motive..." What a stroke of good fortune this would be for Woodward. The years following this first show for strictly "New England" artist would continue to be marred in controversy for the remainder of its existence (1928). He would exhibit at the Boston AC in 1919, 1920, and 1921 before an absence that would run until 1930. While Boston was important to RSW's early career, when it came to the growing trend to feature more American-influenced art, it was behind times. As a movement, American Scene painting was taking shape and Philadelphia, New York and particularly Chicago, were in the forefront. In fact, the 1918 Boston AC exhibition was an attempt to "catch up" with the rest of the nation and still struggled for support from their own membership.

CLICK HERE for more on the 1918 Boston AC Controversy

( Page will open in a new tab)

Tranquil Hour (Redgate)

Tranquil Hour (Redgate)

Typical of RSW's Redgate years, when travel

was limited. He often painted from just outside

the studio these dusk or moonlit wooded

scenes. Especially in the winter months.

These paintings would bring

RSW his first

real notice and national recognition.

RECOGNITION AND REWARD: Flirting with New York

In his second year as a professional landscape artist (1919), Woodward would receive the Academy's distinguished Hallgarten: First Prize Award for his entry, Between Setting Sun and Rising Moon. The Hallgarten prize is given to the best artists under the age of 35. Woodward just made the cut at 34 years of age. Still, given all that he had been through... his accident, four years recovering, his failed attempt to attend the BMFAS, his years squeaking out a living as an illustrator... to win such a prize must have felt like a tremendous triumph and a "career making one" at that. He would see new opportunities open up for him. He would exhibit the next year at the prestigious Carnegie Institute's "International Exhibition of Paintings" in Pittsburgh, PA and at the oldest art academy in the country, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts', "116th Annual Exhibition," in Philadelphia, PA in 1921. Two cities at the forefront of the American Art Scene movement.

As a reminder, Boston and New England still generally valued traditional art influenced by Europe over what was then considered the trending "modern art" of American-styled painters. There were exceptions, small fissures in the New England landscape, particularly the Concord Art Association where RSW exhibited in 1920 winning First Prize in Painting. Also in 1920, the Worcester (MA) Art Museum, would exhibit his work, and in Springfield, MA under the influence of maverick art collector and museum benfactor/founder George Walter Vincent Smith, who would buy 2 of RSW's paintings for his museum. The American Art Scene Movement did not yet take hold; however, its movement was gaining acceptance in a grassroots effort prompted by those of Hudson and Ashcan Schools. Regions such as, the Mid-Atlantic (led by New York and Philadelphia) and the MidWest (led by Chicago and Pittsburgh) were far more accepting and open to including these distinctly American works into their exhibitions. In many ways, NYC led the way for all of them, and MacBeth was the torch bearer. (see "The Eight" for an interesting side story. The link with open in a new tab)

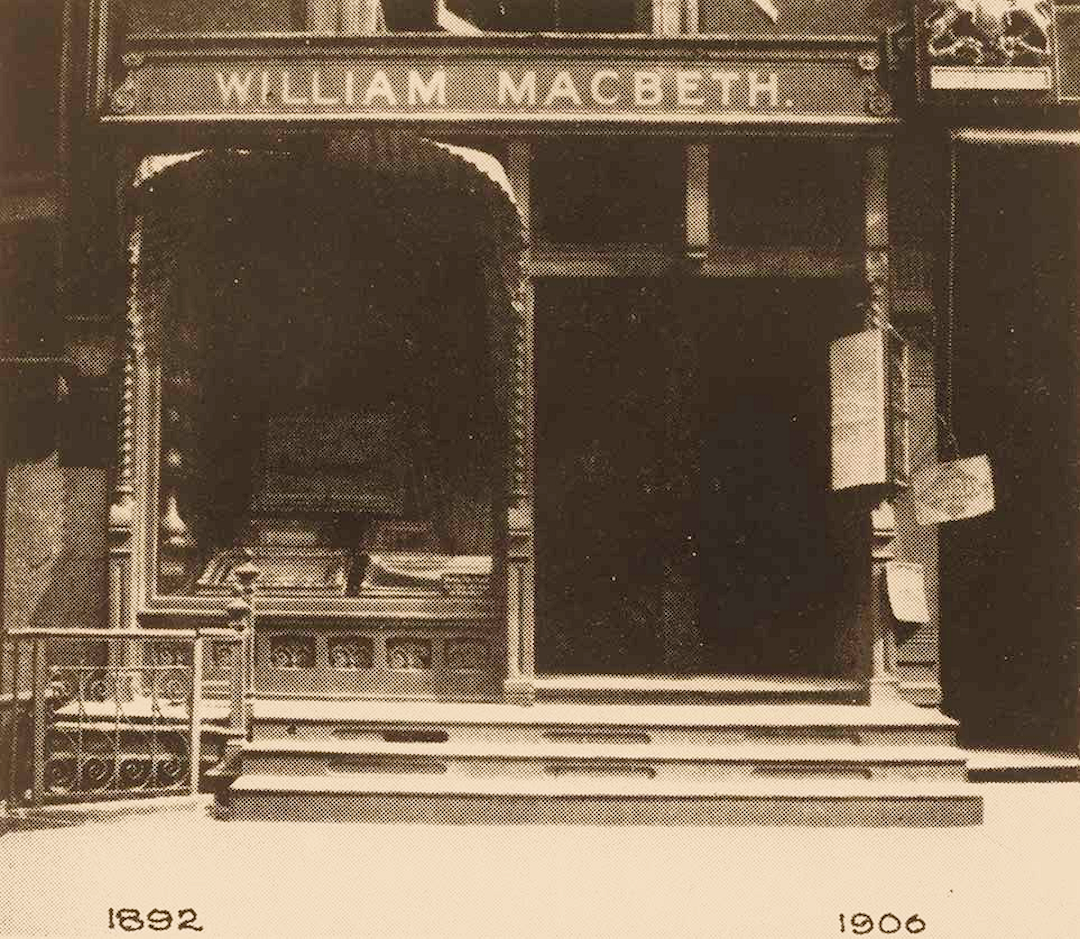

Sometime in the years following the Hallgarten Prize, Woodward was contacted by Macbeth. We do not know the specifics of the arrangement. What we do know is that during the years 1920 and 1921, RSW had prepared as many

A street picture of MacBeth's gallery front 1906

A street picture of MacBeth's gallery front 1906

as 50 paintings to be sent to founder William MacBeth who would then select 25 to feature in the exhibition. The exhibition was slated to run in January of 1923. With the paintings stored in his Redgate studio, the night before RSW was to ship them to NYC, and two days before Christmas, tragedy struck. A fire destroyed the studio along with all but one of the 50 paintings. Reports attribute the cause of the fire to the wood-burning stove inside the studio overheating. While essentially true, it is more likely that RSW did not account for the over-crowdedness of the studio itself. If the stove overheated, it was because he fed the stove the usual amount of wood despite having less "space" to heat. It is also very likely that the temperatures in the studio rose to a flash point for a number of the flameable chemicals often found in an artist's studio, and those chemicals ignited causing the fire.

The fire would have a devastating effect on Woodward's career. Not only would he lose the assets we believe in today's dollar would be practically $300,000 and lose his studio, which needed to be replaced; it would put a wedge between him and MacBeth that would last nearly 10 years! He would not have his first significant One-Man show in NYC until December, 1931, and it would be with MacBeth competitor, Grand Central Galleries. Fortunately for RSW, his popularity would be enough that MacBeth would eventually relent and give Woodward his showing shortly after the Grand Central show.

ABOVE: a picture with RSW's handwriting pointing out

ABOVE: a picture with RSW's handwriting pointing out

where in relation to Redgate the Burnham Cottage is located.

BELOW: is an image of a painting by RSW of the Burnham

Cottage given to the Burnham family, who affectionately

called the cottage, "The Shack."

Leave it to Woodward whose

father worked in real estate to give it an upgrade...

A TRIUMPH: Woodward's Coronation

After the Redgate fire, Woodward would need to search for a new studio. He had already moved out of his aunt and uncle's home (approx. 1914-16) and was living about a quarter mile down the road in the "Burnham Cottage." The cottage sat on the southwest corner of the old 9-acre Hiram Woodward Farm. Hiram is a distant cousin, four times removed. RSW is renting the cottage and so there is little option of fashioning or building a studio. Uncertain about how it was possible; in May 1923, RSW bought the Hiram farm which besides the cottage, included, a house, a barn and a large shed that would make a perfect studio. Like every other place he lived, it would need extensive renovations in order to be liveable and suitable for Woodward's disability. We believe that the farm was vacant and not currently in use, suggesting that it may have been in a state of disrepair. There may be only one thing RSW loves nearly as much as art, and that is re-purposing things, breathing new life into old buildings. He was undoubtedly a preservationist at heart and through himself into such projects allowing his work to suffer (he rarely painted during the Southwick reconstruction). Regrettably, it would not be long for everything to catch up with him.

As mentioned prior, we do not know how RSW managed to afford purchasing the Hiram place. It is unclear if Redgate was insured and even more suggestions that it was not. He was making more money than he ever had as an illustrator but this did not necessarily mean he was flush with money. Oil painting has higher cost and more inherent risk. It is early in his career and still learning (1) how to paint and mix pigments, etc.... (2) develop a name and network for himself, and we simply do not know how many paintings met his standards and how many got destroyed because they didn't. We do know he was struggling six months before the Redgate fire and five months after he buys his first home. Did he get help? If so, who? His family or friends? What is even more striking is that from 1923 to 1925, he only exhibited seven paintings! In 1925, he was in dire financial straits. Only able to cover half his monthly expenses, his friends, the same ones who help him move across the country to attend BMFAS, formed a committee to launch a fundraising campaign to get him back on his feet. They drafted a letter and sent it out among the community to raise $180,000 to cover his cost of living for two years so that he could recover. We have a copy of that letter sent to Mrs. Belle Townsley Smith wife of previously mentioned George Walter Vincent Smith.

Mrs. Smith was then running the museum started by her and her husband. We do not have definitive evidence as to how it came about but during that same period, Mrs. Ada Moore of Pride's Crossing, MA (at the time living in NYC) and who had a wheelchair-bound brother entered Woodward's life and took on his cause creating a trust that would provide for all the considerable cost of his care paying for his nurse and attendant/handyman. Pride's Crossing is just north of Boston, and it could have been through those channels that she became aware of RSW's plight. However, it would seem more likely that Mrs. Smith was the one who made the connection. Both Mrs. Smith and Mrs. Moore were avid collectors of far eastern antiquities (also an interest of Woodward's) and knew each other. In fact, Mrs. Moore lent a portion of her collection to the Springfield Museum in 1928, the year of Mrs. Smith's passing. Mrs. Moore's patronage would remain for the rest of RSW's career extending beyond her death two years prior to him.

The Window: A Still Life and Winter Scene (Hiram)

The Window: A Still Life and Winter Scene (Hiram)

One of RSW's true first "window paintings."

Bought by John Spaulding from the Lyman exhibition

and is to this day held in his collection at the

Boston Museum of Fine Arts

The playing field now leveled for Woodward, Boston would again be fortuitous in re-launch his career. In 1926, RSW would hold his biggest "One-Man Show" to date exhibiting 24 paintings in the second-floor ballroom of the home to finance pioneer Ronald T. Lyman. The home, historically is called the Longfellow House after the famous writer who once owned the home. One Boston newspaper would refer to it as his "coronation" to the Boston art scene. The show itself was a huge success. The first painting sold would be The Window: A Still Life and Winter Scene to renown art collector John Spaulding whose collection remains one of the great treasures of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. RSW would reportedly sell five paintings the opening night and only 10 of the 24 paintings ever exhibit again after. We assume they were sold as well. The event is pivotal in RSW's career for more than just reviving his career. He would never again suffer such financial trouble and pave the way for his triumphant gold-medal honor at the Boston Tercennertary celebration four years later as well as his finally showing his work in NYC. For the first time in his short career, his traditional, impressionistic, atmospheric, deep wood paintings would not out sell his pastoral portraits of rural life. From this point on he would leave that style behind and mature into the natural realism that best suited his personal outlook and values.

CLICK HERE for more on the Fundraising Campaign Letter

CLICK HERE for more on Mrs. Ada Moore and RSW

CLICK HERE for more on the Lyman Residence Exhibition

( Pages will open in a new tab)

The official tercentenary coin

The official tercentenary coin

Latin- Sicut Patribus Sit Deus Nobis

Translation - "As a God to us"

GIVING THANKS: Woodward Honors Boston

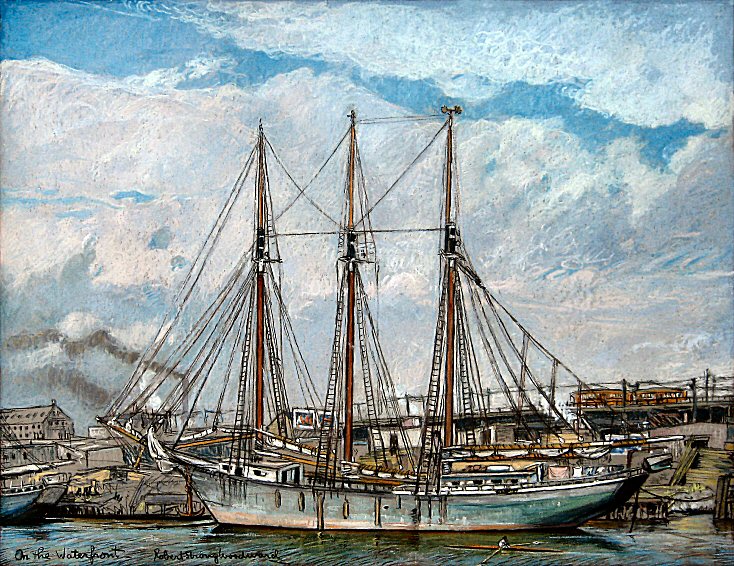

It was not until recently in reading Woodward's 1932 personal diary that we were aware of just how often he would visit Boston. In 1932 alone he made four trips to Boston and had dinner with art collector John Spaulding on two of those occasions. What makes 1930 unusual, besides the tercentenary celebration and spending any significant time away from his home, was that RSW took time to draw a number of chalks depicting the urban Boston scene we affectionately call the "Boston Paintings." The newspaper clipping headline states that RSW intended to paint harbor scenes which he did. First, there is his chalk drawing, On the Waterfront There is also evidence mentioned in two articles, as well as, family lore, that there is a drawing of a man fishing at the end of a pier. Its name and where about are still unknown to us.

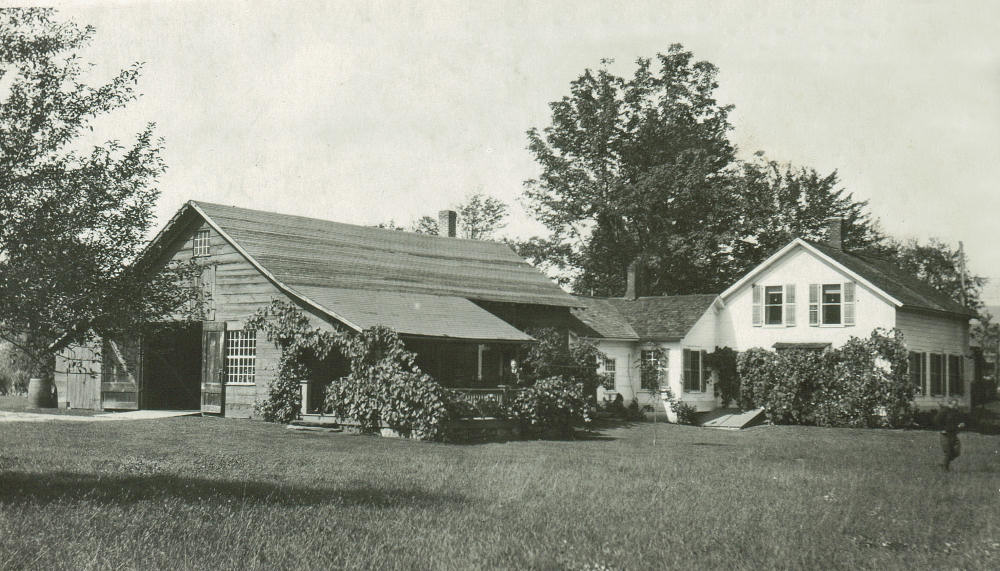

Woodward also went to Old Boston, particularly the Hanover Square area, and drew a chalk drawing of the Ole Oyster House on Union Street. He never names the chalk in his diary comments; however, we do know that he made two oil paintings from that chalk. The first was a 27" x 30" he originally titled, "The Oyster House," that later morphed into,"Boston Romance: The Oyster House" for a couple of years and later still sold at the Grand Central Galleries Founders' Day Show in NYC as just "Boston Romance" and what we now call, Boston Romance: The Oyster House to avoid any further confusion. The other is a 36" x 42" oil he named, In Old Boston. Besides the size, In Old Boston has a number of differences. For one thing, In Old Boston includes a baker in the third floor, center right window, a dog on the sidewalk and mother and daughter after the second parked car, as well as, slight variations of the man and woman coming and going from the storefront (for instance, the man in In Old Boston has newspapers under his arm). In Old Boston would seem to hold a special place in Woodward's heart. It was exhibited only once and was never sold by him. It hung in his home until the time of his death and there after until his estate beneficiary, Dr. Mark Purinton sold it through the annual Boston International Fine Art Show benefiting the Artist For Hunamity, Boston, organization.

On the Waterfront,

On the Waterfront,

Chalk,

22" x 29"

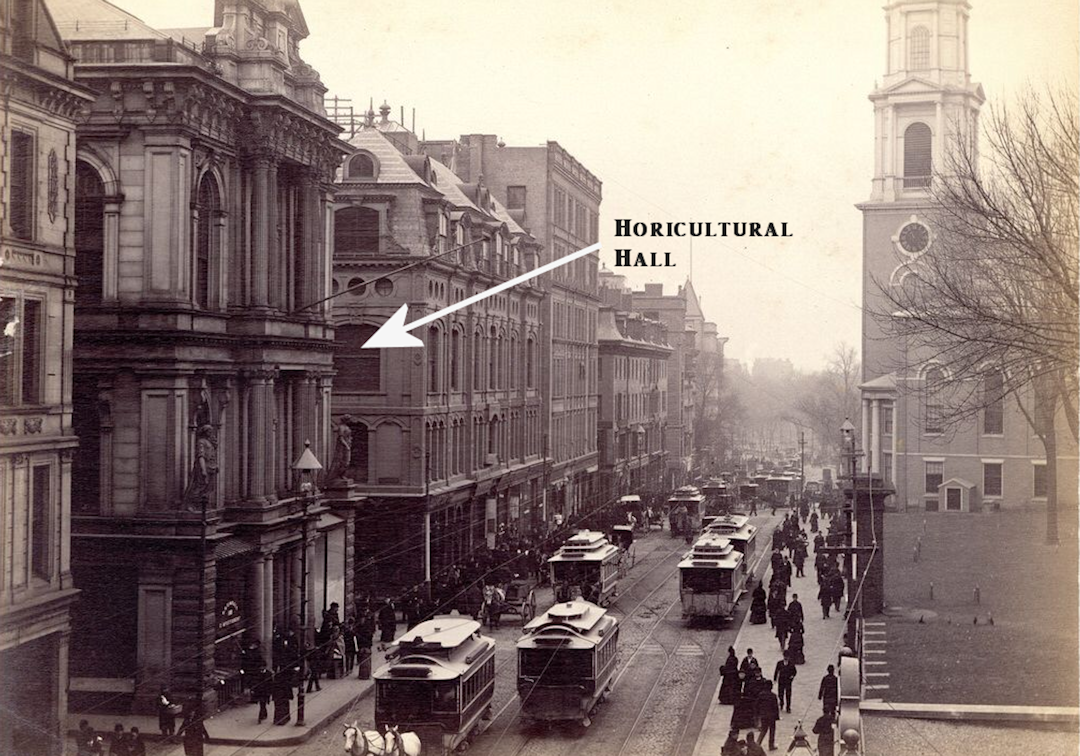

Boston's Horticultural Hall on Tremont Street

Boston's Horticultural Hall on Tremont Street

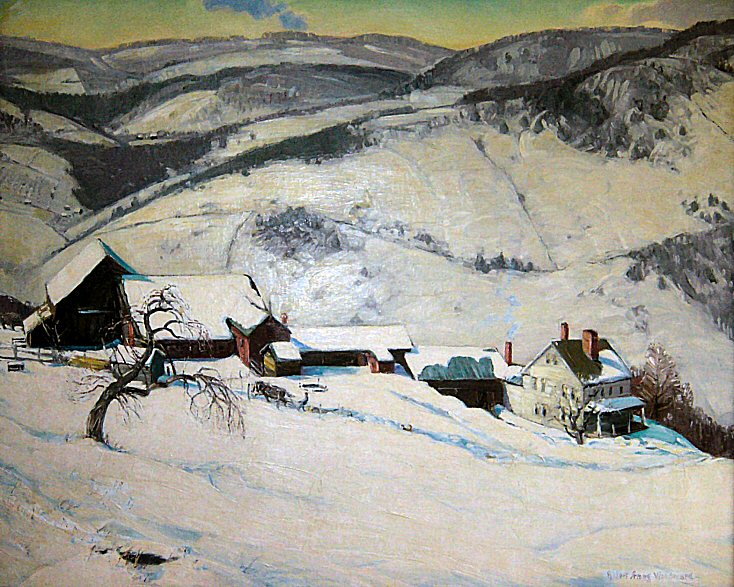

Woodward's 1930 Boston stay is a departure for him for so many reasons: (1) he rarely stayed anywhere for any extended period of time because of the difficulty and expense. (2) In all the years of traveling to Boston to network or collect supplies, these are the ONLY examples of him featuring Boston in his work! (3) The questions surrounding In Old Boston; Chalk addressed above (4) and with that, the chalk drawing of the Ole Oyster House from which he made two oil paintings, appears to be a romantic endeavor of nostalgia and sentiment for which he rarely indulged leaving us with so many questions and few answers. All we have is our educated guesses based on what we do know about him. What is more compelling was a small point of contention that arose from the Tercentenary exhibition. While New England Drama,, drew much praise from Boston area critics, ".....a sturdy well-fixed little farm house under a huddle of fluent hills, is epical and stirring." [F. W. Coburn, Boston Herald, May, 1925] prominent New York critic, RRoyal Cortissoz, while generally admiring it, found it "painty" in its distant hills. A criticism RSW took exception.

In what initially looks to be a bit of an over reaction on RSW's part looks clearer given the greater context of things... At the time, Woodward was negotiating his first One-Man Show in New York City to be held at the Grand Central Galleries. Cortissoz was an art historian and the art critic for the New York Herald Tribune. What adds to the story is that RSW had been shut out of New York since his tragic Redgate fire spoiled his planned 1923 One-Man Show to be held at the MacBeth Gallery in NYC. Given this context, we wonder if RSW making these unusual gestures was an attempt at damage control to protect his upcoming exhibition? It is something we may never know, but the question needs to be asked.

Furthermore, in the simplest terms, the Tencentenary Arts and Craft Show would be the largest event of Woodward's career to date. The show would be attended by over 45,000 people in the span of a month. This and the fact that he was one-of-four artist to receive award honors could suggest he went to revel in the attention and take a bit of a victory lap. Just four years prior, he was on the verge of ruin and now with this event and his future success in NYC. He would be on firm footing for the remainder of his life. In the end, this looks to have been a great gesture of love and respect for Boston and what it meant to him.

CLICK HERE for more detail on the Lyman Residence Exhibition

CLICK HERE for more detail on the 1930 Boston Paintings

( Page will open in a new tab)

The Myles Standish Hotel. Today the old

The Myles Standish Hotel. Today the old

hotel is the Myles Standish Hall dormitory

for Boston University

HAPPY EVER AFTER: The Vose Gallery

There is little question that 1930 was a pivotal year for RSW. One of four painters receiving gold-medal honors certainly put him among the elite. While the 1920s were a struggle, seeing him absent from Boston in 4 of the decade's years, the 1930s and 1940s would be markedly different. From 1930 on, Woodward would hold several exhibits a year there. He especially had a good relationship with the Myles Standish Gallery and Hotel. There are a number of occasions his work hung, on loan, in the hotel's dining room for years and often when a painting was removed it would be replaced with another. The Jordan Marsh Gallery was another popular location his work would be displayed. In 1936, Boston's famed Vose Gallery comes into the picture, and RSW writes in a ledger from January of that year, "These galleries are to be my Boston dealers from now on..." The Vose Gallery had a national reputation. They worked hard to place their artists' work in museums and exhibitions throughout the country.

Vose Gallery on Boyleston Street by Coplay Square

Vose Gallery on Boyleston Street by Coplay Square

Through Vose, Woodward would hang in the Dallas (TX) Museum of Fine Art (1937), the Clearwater (FL) Art Museum (1937), the Toledo Museum of Fine Art (1937) and the High Museum in Atlanta, GA (1948). RSW would also take part in one of the most interesting annual exhibitions of art, the Springville (UT) High School's International Exhibition of Art. Do not let the "high school" or Utah throw you. This was a world-class exhibition of art, every bit what you would find in any other major metropolitan area in the country. Their humble beginning to world-class exhibition is a great Cinderella story RSW would surely appreciate. It survives to this day. RSW sent at least one painting a year from 1935 to 1947. The event was suspended from 1942 to 1945 due to WWII. In 1970, the Deerfield Academy's American Studies Group sent out a mailing to over 500 museums and galleries seeking information they may have had regarding Woodward. Digging through the archive held at Deerfield's Boyston Library, we learned that S. Morton Vose responded and told two terrific recollections regarding RSW. They can be read by CLICKING HERE

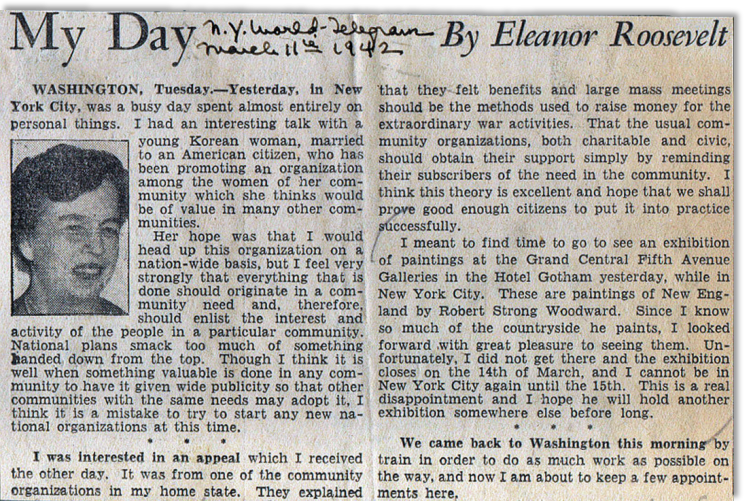

"My Day" column New York World Telegram,

"My Day" column New York World Telegram,

March 11, 1942

It is necessary to point out that RSW was sharing equal, if not slightly more success in NYC. Just months after his first One-Man Show at the Grand Central Galleries, MacBeth finally softened on his stance with Woodward and though smaller in scope, gave him a show. Now established as a bankable artist, he would be a frequent exhibitor at both galleries for the remainder of his career. The highlight of his career in NYC would have to be when First Lady Elanor Roosevelt in her March 11, 1942, My Day national column laments her possibly missing his exhibition at 5th Avenue's Grand Central Gallery, which would be closing the day before she arrives in New York. Needless to say, Woodward and the gallery accommodated the First Lady by extending the show another week. So this begs the question, with strong regional allegiances being firmly held in this period of American history, Woodward's success in NYC seems to blur the lines. Geographically, his location perched him on the fence between both Boston and NYC, and he seemed to identify more with the New Yorkers who roughed it in his neck of the woods in Heath and Halifax (VT). What exactly did Boston mean to Woodward?

There were three pivotal moments Boston played a significant roll in Woodward's career. 1918, when the Boston AC loosened their policies on non-traditional artwork... 1926, when Boston's socialite, Ronald Lyman hosted his first featured One-Man Show and finally in the 1930 Tercentenary gold-medal honor. One could argue, three of the biggest moments in his career. The only exception being the 1919 Hallgarten Prize at the annual National Academy exhibition in New York City. However, what makes for a great romance? Is it a few shining moments of spectacular or is it the one that fills in the gaps, is truer and more personally satisfying? It is the great rhetorical question.

The Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, today.

The Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, today.

Woodward's Tangled Branches was excepted by jury and

exhibited there for its 116th Annual Exhibition in 1921.

A critical examination of the evidence suggests that Boston never truly embraced Woodward. We have already established that his career as an illustrator was sustained by his Midwestern connections. His early appearances at the Boston AC, as well as other New England artists, was under a cloud of controversy. He would eventually be accepted membership but not for another 10 years. The 1926 exhibition was hosted by an individual and not a gallery or museum. Famed art collector John Spaulding who continued a friendly relationship with RSW long after 1926, however, as far we know, never bought a second painting from him. RSW would exhibit at the Boston Museum of Fine Art once (1933). Then there is Vose, for every intent and purpose did a great deal to expand his exposure to other regions of the country, did not take him on as a client until 1936, 11 years after the start of the American Scene Painting movement. A movement that would just be prominent another four to eight years. Arguably late to the game, which is the overall knock on Boston. It was simply slow to embrace the nation's trend towards art of a distinctly American influence. Boston was displaced by the more progressive New York (Ashcan School), Philadelphia (New Hope School) and particularly Chicago whose region, the Midwest, would become the prevailing center of influence for the American Art Scene Movement (Grant Wood's American Gothic and Edward Hooper's Nighthawks). This is why Boston never amounted, to us, as more than a romantic notion of Woodward's.

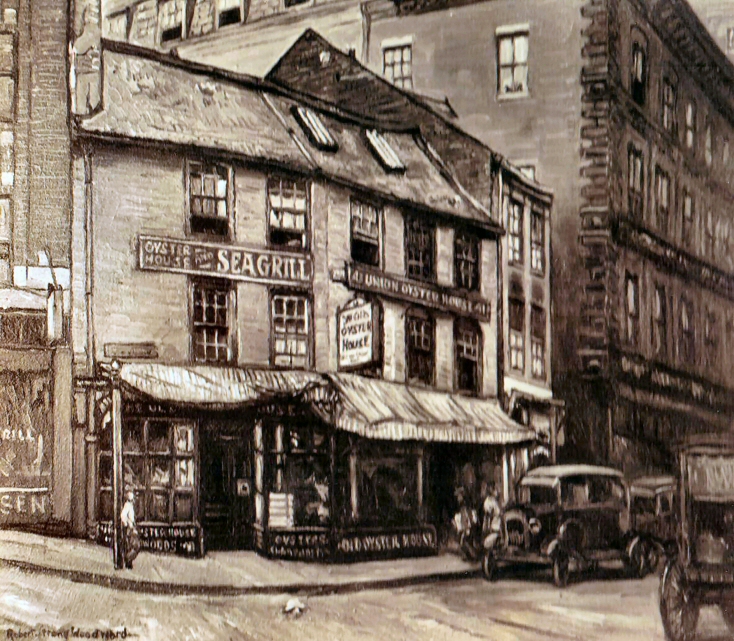

Chicago World Fair's Festival Hall designed by

Chicago World Fair's Festival Hall designed by

RSW bookplate client Francis Meredyth Whitehouse.

The hall housed the fair's art exhibit and was visited

by close friend Clifton Richmond.

Woodward shared a close relationship with Robert Bartholow Harshe, Director of the Art Institute of Chicago who as curator for the 1933 Chicago's World Fair exhibition invited Woodward to display his work, reportedly the only New England artist invited! He would exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago (1930, 1933 and twice in 1937) more than the BMFA. His most loyal customers were Bartlett Arkell (NY), Adeline Havermeyer Frelinghuysen (NJ, VT) and Josephine Everett (OH, CA). Both Arkell and Everett contributed to his work hanging in museums. His closest friends were actress Beulah Bondi (NY, CA) and founding member of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences, Harold Grieve (CA). Grieve was instrumental in putting RSW's work in the homes of Hollywood's elite ( Burns and Allen, Benny, and producer Leonard Hyman). Although it was spoiled by his Redgate fire, New York was the first to seek him out for a featured exhibit. Not only that, the Philadelphia Acedemy of Fine Art accepted his work in its featured annual exhibition (1921) and not as second-class, special circumstance, consolation show.

FOR MORE Famous Owners CLICK HERE

FOR MORE RSW's Friends CLICK HERE

( Page will open in a new tab)

Woodward's window paintings best illustrate

Woodward's window paintings best illustrate

the synonymous relationship he felt for home

being as much what is seen from the heart.

OUR CONCLUSION: His legacy as a New England Artist

We try to imagine how different Woodward's career would be if, let's say, he attended the Art Institute of Chicago, rather than BMFAS. He had a strong support system already in place there with Peoria close by. His very close friend, Victor West, there when he suffered his tragic accident, was also teaching at Northwestern University the years he could have studied in Chicago. Would he have actually completed his training? What if he chose to live somewhere in upstate New York or in Illinois? Perhaps, near Schenectedy where he had strong ties to the Schermerhorn family among others? How would things have been different for him? Would he be well-known or at least a better known name?

Entertaining such thoughts is nothing more than folly, an exercise in speculation from the perspective of our hindsight. We are not trying to "re-envision" RSW's life or question his choices. Life takes us where it takes us and often our perspective is not broad enough to see what is best. Even so, there appears to be no greater influence on Woodward than his upbringing. The evidence that there was a bit of resentment towards, if not his father himself, certainly his father's career as a real estate developer. He and his family being traipsed about the country from one town to another, often living in temporary housing or worse yet hotels. Could we attribute his desire to go to Boston, no matter the fit, as simply his identification to it as "home' despite considerable evidence to the contrary? Yes, he spent nearly every summer with his family in Buckland, but he was raised in the Midwest, an influence that just simply cannot be ignored. While he related to Boston familiarly, he did not seem to identify with it in terms of style preference and philosophical bent.

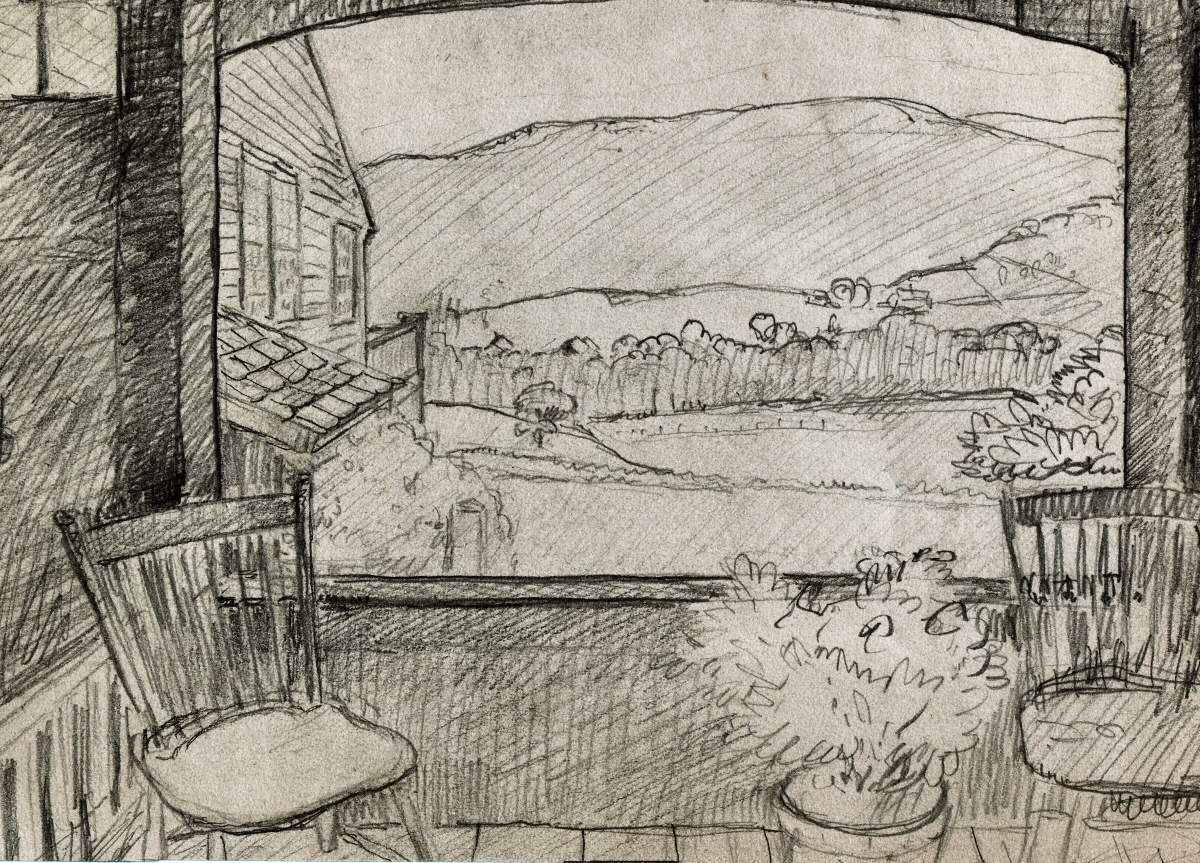

Of everything Woodward ever created,

Of everything Woodward ever created,

this simple sketch drawing of the breezway

between his home and studio may

encapsulate ALL his beloved NE meant to him.

There was a strong connection to the area. He loved Buckland and Shelburne Falls deeply. And given his condition, there seems to be no more an appropriate place for him to settle down and finally plant roots. The area is insular. The world undoubtedly feels small and manageable when in the confines of its abundant and rolling but not too big hills. He had family and was loved very much. While an ideal place to live given his condition (he could safely get about without too many obstructions or dangers). It was arguably more difficult for a paraplegic naturist with middling leanings and distinctly broader American perspective, already marginalized by his condition, to displace himself further in such a remote location. (Which oddly enough is almost dead center New England geographically. From Shelburne Falls, it is nearly the same distance to every state capital in the northeast within a plus/minus of 20 miles, including Albany and excluding Bangor, ME.)

Maybe that was the genius of RSW. New England at the time was facing "social economic" realities beyond its control- the abandon farm, decaying buildings and plight, in many ways caused by the mass exodus of people chasing the American dream by pouring into the cities or heading to the wide-open west. There is considerable evidence that much of the country held no sympathy for the situation NE found itself. The general attitude was that New Englanders had no one to blame but themselves for not being more progressive and keeping up with the rapid change. They were considered "shiftless" meaning, lazy or not ambitious, because they stayed with their homes! Imagine what a man, for all intents and purpose that suffered a tragic accident at his own hand but not by any fault of his own; the ill-fatedness of the event, but yet, one which he can surely not be blamed. Now imagine shaming him for it? His desire for roots, a home and his beloved NE being nationally shamed and derided for steadfastly clinging to theirs... he championed New England and its people. While Boston may not have been ready or welcoming of Woodward, in the end, we do not think it mattered to him. When and all is said and done, we believe he would have ended up in Buckland/Sherburne Falls regardless. So school didn't work out, it only brought him "home" sooner. He made his way like we all do.